WASHINGTON – The Supreme Court on Wednesday grappled with the question of whether two Arizona death-row inmates can pursue new claims in federal court, or whether federal law prohibits hearings into those claims.

Barry Lee Jones, convicted in the 1994 murder of a 4-year-old girl in Tucson, said his trial attorney failed to develop evidence that could have raised doubts about his guilt. David Ramirez, convicted in the 1989 murder of his girlfriend and her teen daughter in Phoenix, said his attorney did not present evidence that might have spared him the death penalty.

In separate rulings last year, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered new hearings for both men, citing the Supreme Court’s ruling in a 2012 case from Arizona, Martinez v. Ryan. Martinez created a narrow path for inmates to pursue ineffective assistance of counsel claims in federal court, even if they were not raised in their state appeals first, if the trial attorneys’ errors were “substantial.”

But the state argued Wednesday that Congress set an “intentionally high bar” on such appeals under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 to sharply limits such claims. In its appeal to the high court, the state said that the 9th Circuit’s ruling was “precisely the opposite” of what AEDPA requires, and should be reversed.

“Martinez’s judge-made rule cannot rewrite Congress’s statutory standard,” said Arizona Solicitor General Brunn Roysden III, telling the justices that “Congress spoke clearly” in AEDPA and the courts’ job is to apply that law.

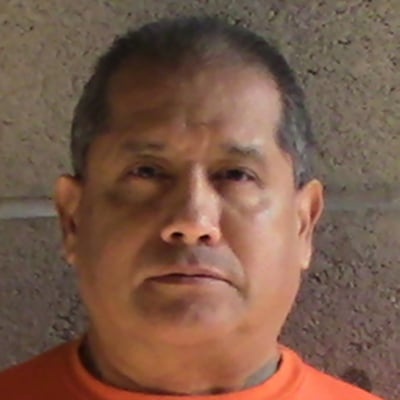

David Ramirez has been on Arizona’s death for 30 years for the 1989 stabbing deaths of Mary Gortarez and her daughter, 15, in their Phoenix apartment. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections)

The justices appeared to struggle with how to balance AEDPA with Martinez. Justice Brett Kavanaugh said it was “hard to envision” the court identifying an “important right” in Martinez for a defendant to raise an issue, if it knew AEDPA would make that issue impossible to pursue, as Roysden argued.

“The court obviously crafted an opinion to give you the right to raise an ineffective assistance claim, to make sure it’s considered at least once, and this would really gut that in a lot of cases,” Kavanaugh said.

In response to a question from Justice Clarence Thomas, the attorney for Ramirez and Jones said that the exception created in Martinez does not “eviscerate” AEDPA, because it is limited to issues raised on direct appeal.

The attorney, Robert Loeb, said that because of the way Arizona structures capital cases, what is considered post-conviction review in other states is actually part of the direct appeal process in Arizona, and thus eligible for appeal under Martinez.

“It walks like a duck, quacks like a duck,” Loeb said of Arizona’s post-conviction review. “It is a mandatory review, just like an appeal.”

Ramirez was convicted on two counts of first-degree murder for the May 25, 1989, stabbing deaths of his girlfriend, Mary Gortarez, and her 15-year-old daughter at Gortarez’s Phoenix apartment. There was little question that Ramirez, who police found in the apartment intoxicated and covered in blood, was the killer.

He was sentenced to death after a judge found no mitigating evidence to offset the “heinous, cruel or depraved” manner of the murders.

Jones was convicted of murder, sexual assault and child abuse in the May 2, 1994, death of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter, who was pronounced dead on arrival after she was taken to the hospital with severe cuts and bruises. Witnesses said the girl had been in Jones’ care, with some saying they saw him beat her, in the hours before she died.

Barry Lee Jones has been on death row since 1995 for the sexual assault and murder in Tucson of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections)

Despite potentially mitigating evidence of a troubled family background, he was sentenced to death based on the age of the victim and the “especially cruel” nature of the killing.

But Jones said his attorney failed to produce experts who would have said the girl’s injuries could have been inflicted days before her death, not just in the hours when she was in his custody.

And Ramirez said his attorney, who had never tried a capital case before, failed to present evidence of his low IQ and a history of abuse, sexual assault, neglect and developmental issues that even a dissenting judge described as the “truly deplorable conditions of his upbringing.” Ramirez’s trial attorney agreed, saying she was not prepared to represent “someone as mentally disturbed as David Ramirez, especially in a capital case.”

Roysden said the solution to those claims is not a federal appeal but to “go to state court and file a second or successive … petition” to plead their innocence.

“Most states allow innocence as a ground. In Arizona, we allow that,” Roysden said. “So you could go to court, you could develop … your record in state court.

“And I think that’s the answer given the statutory requirements of AEDPA, which are very strict in this context,” he said.

Loeb compared that to playing five-on-one basketball then, at the end of the game, giving the one player “a shot from half-court, and that’s going to make it fair.”

“There is a right to have trial counsel here, and there was never a fair trial for Mr. Ramirez or for Mr. Jones,” Loeb said. “And the fact that they give a Hail Mary opportunity for relief at the end of the day, or can give a pardon to Mr. Jones, that does not mean the right to effective trial counsel is being vindicated here.”