Although many farmers are glad to see that progress is being made toward addressing USDA discrimination, Stewart said it will take more than forming a committee to fix the generations of systemic racism and discrimination.

“The committee and all of these things are nice, but results are what really matter,” she said. “The equity part is important, but you need the right people handling it.”

“You can’t change that 1.4% without taking care of the farmers that are already there,” said James, her husband. “By lending that 1.4% more money to help them grow, that’s a great thing, but it doesn’t change that 1.4% by lending money to the same people.”

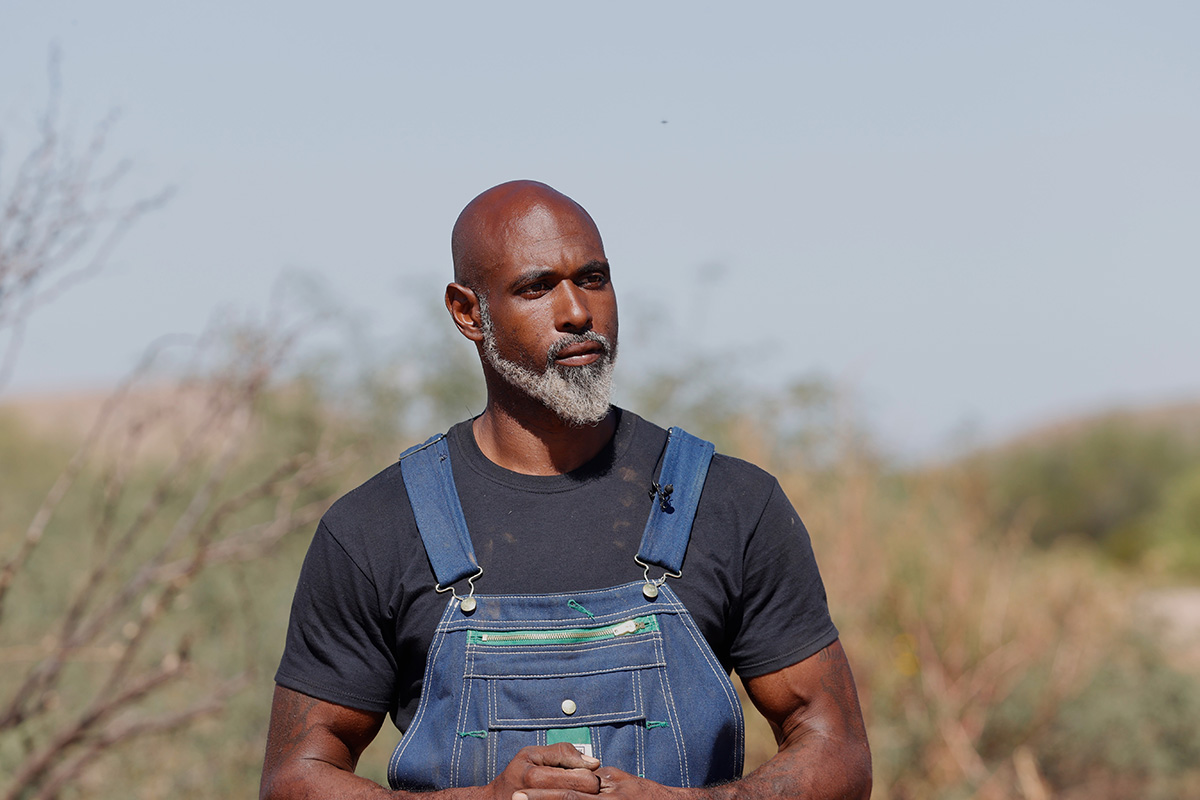

James sees their ranch as an opportunity for their family to continue farming for generations to come. He said by the time their kids are 18, they’ll be prepared to take it over and continue to help it expand.

“The education is right here for our children; they’ve got blood, sweat and tears in it,” James said. “They can start making their own decision, putting their input in it and putting their stamp on it, and they can just continue to grow it. Then when they have children, next thing you know, that’s three generations. As long as we continue to grow and build it, it’s going to make a change.”

Goldmon, who’s a third-generation farmer himself, said most farmers of color have parents and grandparents who over the decades were left out of USDA discussions and denied access to resources and opportunities that were widely available to white farmers. But when effective policies are implemented correctly, he said, farmers of color can build on the successes of their forebears.

He said success in his position would mean that the commission no longer would be needed and all farmers would be treated equally.

“When you look at where we are today, I don’t know that four or even eight years is long enough to adequately address all of these issues, but I continue to keep that as my goal,” he said. “These changes won’t happen overnight, but I think if we are cognizant of that fact, and can be open minded enough to look at not just the programs but the underlying situations, we will make sufficient progress.”