WASHINGTON – An appeals court Thursday rejected an Arizona death-row inmate’s argument that his sentence was unconstitutional because his crime, burning a former roommate to death, was committed in a brief window when the state was revising its death penalty law.

A three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals also flatly rejected Leroy McGill’s claims that his conviction should be overturned because his attorney did not adequately represent him.

The court said the work by McGill’s attorney was “thorough and expansive” and that whatever shortcomings there were in the defense case were due to “the weakness of her case and not her ineffective assistance.”

Circuit Judge Milan D. Smith agreed with the majority that McGill’s conviction should be upheld, but said in a partial dissent that the sentence of death was unconstitutional.

“LeRoy McGill could not have been sentenced to death for murder when he committed his crimes because at that time there was no statute implementing the death penalty in Arizona,” Smith wrote.

But Circuit Judge Jay S. Bybee wrote in the majority opinion that McGill knew that the state could seek the death penalty for the murder.

“Arizona did not impose a penalty that was previously unavailable, nor did the state criminalize innocent conduct after the fact,” Bybee wrote. “The state ‘simply altered the method … employed in determining whether the death penalty was to be imposed.'”

Attorneys in the case did not respond to requests for comment, but one public defender said his office was “disappointed with the 2-1 decision.”

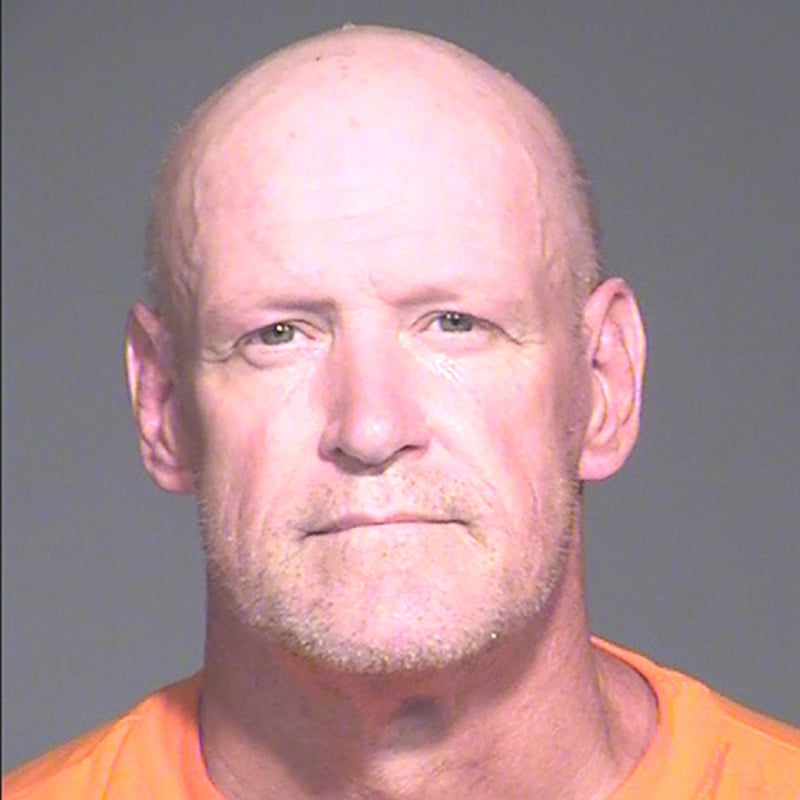

A federal appeals court rejected Leroy McGill’s argument that he should not have been sentenced to death in the 2002 burning death of his Sunnyslope roommate. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections. Rehabilitation and Reentry)

“The crime Mr. McGill was convicted of committing occurred after the Arizona death penalty statute was declared unconstitutional … and before the state legislature fixed the statute,” said Dale Baich, an assistant federal public defender in Arizona.

The case began on July 13, 2002 – halfway between a June 24 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that overturned Arizona’s death penalty law and the Aug. 1 action by state lawmakers that fixed the law by giving jurors, not judges, the authority to impose the death penalty.

It was on July 13 that McGill confronted Charles Perez, a former roommate in a Sunnyslope duplex who accused McGill of stealing a shotgun from a duplex they were living in. McGill was kicked out of the duplex, but subsequently came back to teach Perez “a lesson, that nobody gets away with talking about” McGill and his girlfriend at the time, according to court documents.

McGill found Perez and his girlfriend, Nova Banta, on a couch in the duplex, where he doused them with gasoline and threw a lit match at them, causing third-degree burns that covered 75% of their bodies. Perez died the following day but Banta survived, allowing her to identify McGill.

McGill was indicted in March 2003 on charges of murder, attempted murder, arson and endangerment. He was convicted on all charges in October 2004 and sentenced to death a month later, based in part on the fact that he was a previous felon and had committed the murder “in an especially heinous, cruel, or depraved manner.”

In his most recent appeals, McGill argued that his attorney failed him by, among other things, not obtaining and retaining necessary expert witness and evidence, not spending sufficient time on the case, not digging into records that would show a troubled childhood and addictions, and more.

McGill said his attorney should have made a stronger case for mitigating circumstances that would have weighed against the imposition of the death penalty. Those included claims that he was sexually abused in a foster home, that he suffered brain injuries and that he began drinking alcohol at age 9, progressed to marijuana by age 13 and was a “chronic, daily methamphetamine” user by the time of the murder.

But a U.S. District Court judge rejected the ineffective assistance of counsel claim, noting that McGill’s attorney spent four days at his sentencing hearing presenting evidence of mitigating factors.

The circuit court on Thursday upheld that ruling, saying McGill’s attorney generally did her job. While she could have looked for more issues in his past, the court noted, attorneys are not required to “scour the globe on the off chance something will turn up.”

“McGill’s counsel presented extensive mitigation evidence and diligently attempted to discover much more,” Bybee wrote.

Baich said his office is considering next steps in the case, but was disappointed that the court did not agree with Smith on the constitutionality of the death sentence in McGill’s case.

“Judge Smith agreed with our argument that the death sentence should be vacated because that penalty was not statutorily available at the time of the crime,” he said.