WASHINGTON – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez told a Senate panel Wednesday that special protections are needed to reverse the “very disrespectful” treatment of Native Americans who face extraordinary challenges in the voting process.

Nez joined others urging a Senate Judiciary subcommittee to support the Native American Voting Rights Act, which would set minimum federal requirements for voting on tribal lands, including early voting, mail-in balloting, ballot collecting and ID standards.

“It’s not about Democrat or Republican,” Nez said. “It’s about doing the right thing.”

This includes addressing the many voting barriers that are unique to Native Americans, such as the lack of voting locations on reservations, which makes it difficult for them to vote, Nez said.

“Traveling to polling places can be particularly burdensome,” he said.

But critics at the hearing said the bill goes too far and would open tribal voting to abuse and fraud.

“I agree that we should vigorously protect every American’s right to vote,” said Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas. “But unfortunately this bill … would expand voter fraud rather than combat it.”

Cruz accused Democrats of using voting rights as a cover for election reforms aimed at “seizing power and ensuring Democrats stay in power for the next 100 years.”

The hearing came less than an hour after Senate Republicans blocked debate Wednesday on the Freedom to Vote Act, a voting rights bill aimed at all Americans that would expand voter registration, increase early and mail-in voting and make Election Day a national holiday, among other measures.

That bill was a slimmed-down version of the House-passed For the People Act, which Senate Democrats had amended in hopes of getting some Republican support. But all 50 Senate Republicans voted against it Wednesday, denying Democrats the 60 votes needed to end a filibuster and proceed on the bill.

The Native American Voting Rights Act was introduced in August by Sen. Ben Ray Luján, D-N.M., and has 17 co-sponsors, all Democrats. One of those co-sponsors, Sen. Alex Padilla, D-Calif, said the bill is needed to “ensure that Tribal communities are not denied equal participation in our democratic process.”

The bill would allow tribes to specify locations of voter registration sites, ballot drop boxes and polling locations on reservations and requires states to accept tribally issued ID cards as valid voting identification. It would also make it harder for states to cancel polling places, set minimum standards for early voting and require that states allow voters to give their ballot to someone else to deliver – even in states, like Arizona, that otherwise prohibit such so-called “ballot harvesting.”

Sara Frankenstein said the bill is too broad and “takes control over elections out of the hands of the election administrator, for which he is trained and elected. This raises several legal and practical concerns.”

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez, left, and Sen. Ben Ray Lujan, D-N.M., the lead sponsor of the Native American Voting Rights Act that would extend new protections to the vote on tribal lands, talk before a Senate Judiciary subcomittee hearing on the bill. (Photo by Diannie Chavez/Cronkite News)

Frankenstein, a South Dakota attorney who represents election officials and handles election law cases, pointed to the bill’s requirement that Native American voters can have their absentee ballots sent to a public building, since many homes on reservations do not have street addresses. Having hundreds of ballots arrive at a public building – and with no person in charge – can lead to fraud because there is no way to know the ballot was received by the correct owner, she said at the hearing.

“This is a solution in search of a problem,” Frankenstein said.

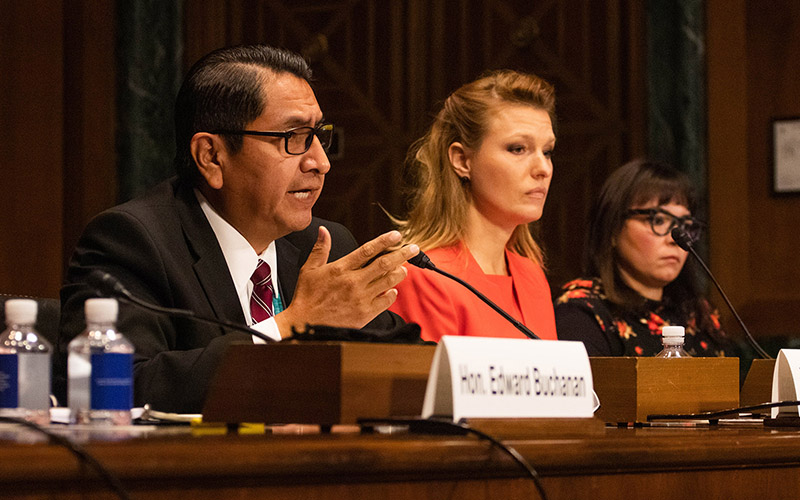

That was echoed by Wyoming Secretary of State Edward Buchanan, who said that the measures would not increase security or confidence in the vote but would only lead to doubt in the election process.

“You cannot have an election that people don’t believe in,” Buchanan said. “Because if they don’t believe that the result has integrity, you will drive down election participation.”

He pointed to the ballot harvesting requirement, which said states “may not allow any limit on how many voted and sealed absentee ballots any designated person can return.” That would lead to fraud because there would be no way to know that absentee ballots were delivered to a registered voter.

“There is no way it can’t happen, and the hard part is that you won’t even know that it is happening,” Buchanan said.

But supporters said ballot collections, drop boxes and absentee ballots address very real problems on tribal lands.

In the 2018 election, Navajo voters in Arizona had to travel up to 236 miles round trip to participate in early voting, Nez said. Tribal members may not own a vehicle that will let them make that trip on their own, and many may not have mailing addresses needed to get a mail-in ballot.

Jacqueline De León, staff attorney for the Native American Rights Fund, said the difficulty Indigenous voters face “also communicates to Native Americans that their vote is unwelcomed.”

“What is being communicated … is that your vote doesn’t matter and that you’re not part of the American system,” she said.

De León said the lack of home addresses on tribal lands and requirement of an ID in some states are examples of “ongoing discrimination and governmental neglect.”

“Many Native Americans live in overcrowded homes that do not have addresses, do not receive mail, and are located on dirt roads that can be impassable in the wintery November,” De León said.

De León and Nez rejected the fears of fraud raised by critics, saying protections are still built into the law and election fraud would still be illegal. They pointed instead to the rights that are being denied under the current law, which is why the new law is needed.

“We need to make sure the rights of Indigenous peoples are protected,” Nez said. “There should be a responsibility to fight for Indigenous peoples’ rights.”