PHOENIX – When construction worker Lorenzo Tejeda moved to Arizona in November 2019 after living in San Diego his whole life, he had to make a lifestyle change to properly adjust to working in the Arizona heat.

“I had to change the way I ate, I had to change the way I hydrated, I had to change the way I exercised in order to condition my body to be ready to work possibly eight to 10 to 12 hours outside in 115 degree heat,” Tejeda said. “It was a long process and it was a complete lifestyle change.”

Tejeda is the safety and environmental manager for Markham Contracting, a construction company in Phoenix.

On Sept. 20, the Biden administration announced a new effort to protect workers like Tejeda from heat related illness in the U.S. Before this, there were no federal regulations for heat protection or mitigation for workers or communities.

“Rising temperatures pose an imminent threat to millions of American workers exposed to the elements, to kids in schools without air conditioning, to seniors in nursing homes without cooling resources, and particularly to disadvantaged communities,” President Joe Biden said in a news release.

At Biden’s request, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is launching a rulemaking process to develop a workplace heat standard, implementing an enforcement initiative on heat-related hazards, developing a national program on heat inspections and forming a working group to engage stakeholders and coordinate with state and local officials.

For Tejeda, the president’s move doesn’t mean any major changes in how Markham handles heat related issues on jobsites. Tejeda said the company currently provides electrolyte packets to workers who need them, and people are encouraged to follow proper nutrition and drink plenty of water.

For his company, Tejeda said, Biden’s announcement is directed more “towards the compliance side from state inspectors and audits. As more information comes out, it may change the way we mitigate heat, but for now we will be continuing to document and inspect our job sites while exceeding the OSHA standard.”

Although no legislation exists at the national level for heat response, Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, is working to pass the Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act, which would require the U.S. Department of Labor to make an occupational safety or health standard for extreme heat prevention. The measure now is in the Senate.

“Hopefully, the employers will join in and we can make this a transition for more protection that doesn’t require the controversy and the divisiveness that other issues are providing right now,” Grijalava said.

However, the Biden administration’s latest move accomplishes some of what the act would do.

OSHA will implement heat related interventions and workplace inspections when the heat index reaches 80 degrees or higher. The heat index is how hot it feels relative to the outside humidity factored in with the actual air temperature, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In Arizona, 80 degrees – which may seem mild in states with high humidity – is the starting point to watch for signs of heat exhaustion, said meteorologist Jaret Rogers with the National Weather Service in Phoenix.

“We actually use impact data from the Centers for Disease Control to look at what level temperatures start to affect people,” Rogers said. “Usually during the summer, it’s about 105. That seems to be one of the thresholds that we use for excessive heat warnings, but really, temperatures in the 90s, even upper 80s, there’s plenty of sunshine if you’re out and exposed for a long time (heat) can start to cause problems for people. “

Although only California and Washington have heat specific standards for outdoor workers, the general duty clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 states that “employers are required to provide their employees with a place of employment that ‘is free from recognized hazards that are causing or likely to cause death or serious harm to employees.’” However, this clause isn’t specific to heat related mitigation strategies.

Heat records and illnesses

The administration’s push comes at a time when much of the West was gripped by record heat, including Washington and Oregon, where many buildings don’t have air conditioning. Hundreds of people died this summer in the Pacific Northwest because of extreme heat. Arizona also had above average temperatures in 2021, according to NOAA, which declared July the Earth’s hottest month on record.

“We had a record hot summer across the state last year (2020), and this summer is much cooler, especially in Phoenix, Southern Arizona,” Rogers said. “Where the state is actually still above normal, though, if you look at the statewide counters in July and August, we were actually the 20th warmest on record.”

Phoenix has warmed 4.3 degrees since 1970, according to Climate Central, and Arizona has warmed 3.2 degrees.

Mark Hartman, chief sustainability officer for Phoenix, said heat is “like a silent storm. … It’s not as dramatic if you’re watching it on camera compared to a hurricane or tornado.”

Outdoor workers are particularly impacted.

“With no climate action, more than half of the counties with a high proportion of outdoor workers (defined as counties in which more than 25 percent of people work outdoors) would experience 30 to 90 days per year with a heat index above 100°F,” according to “Too Hot to Work,” a study from the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Heat associated deaths and heat illness is an issue across the U.S., and those numbers are expected to continue to go up. In Maricopa County, the number of heat associated deaths was much greater in 2020 than in past years. In 2020, there were 323 heat associated deaths in the county.

Rogers said the national data for heat associated deaths are “unreliable.”

“They seem to be underreported quite a bit,” Rogers said. “There’s a lot of reasons for that, in every state has a different way of reporting these numbers, so it’s hard to get a consistent number for each state.”

Experiencing heat

In Phoenix, which is one of the fastest warming cities in the country, the urban heat island effect contributes to the extreme heat. Ariane Middel studies urban heat scapes and how pedestrians experience heat at Arizona State University.

“As the sun hits the surfaces during the day, they store the heat, almost like a battery, and then at night they release the heat slowly,” Middel said. “So when you look at the air temperature difference in the evening and at night between the desert and the city, the desert will be cooler and that’s the urban heat island. The city stays warmer at night than the surroundings because of asphalt and the concrete.”

Middel said people usually think of heat in terms of air temperature, but surface temperature and radiant heat also play roles. Radiant heat is how we experience heat, it factors in the energy that reflects off surfaces as well.

“That’s a heat metric that more closely relates to how we actually experience that heat, and it’s the total of all energy that hits your body,” Middel said. “So it’s the direct sunlight from the sun, if you’re not in the shade, it’s the heat that comes off of an asphalt surface, for example, when you are standing in a parking lot and it’s all of this heat that surrounds you, hits your body and it’s absorbed by your body.”

The lack of overnight cooling in Phoenix is a concern, because there’s less time for the body to cool off from the daytime heat.

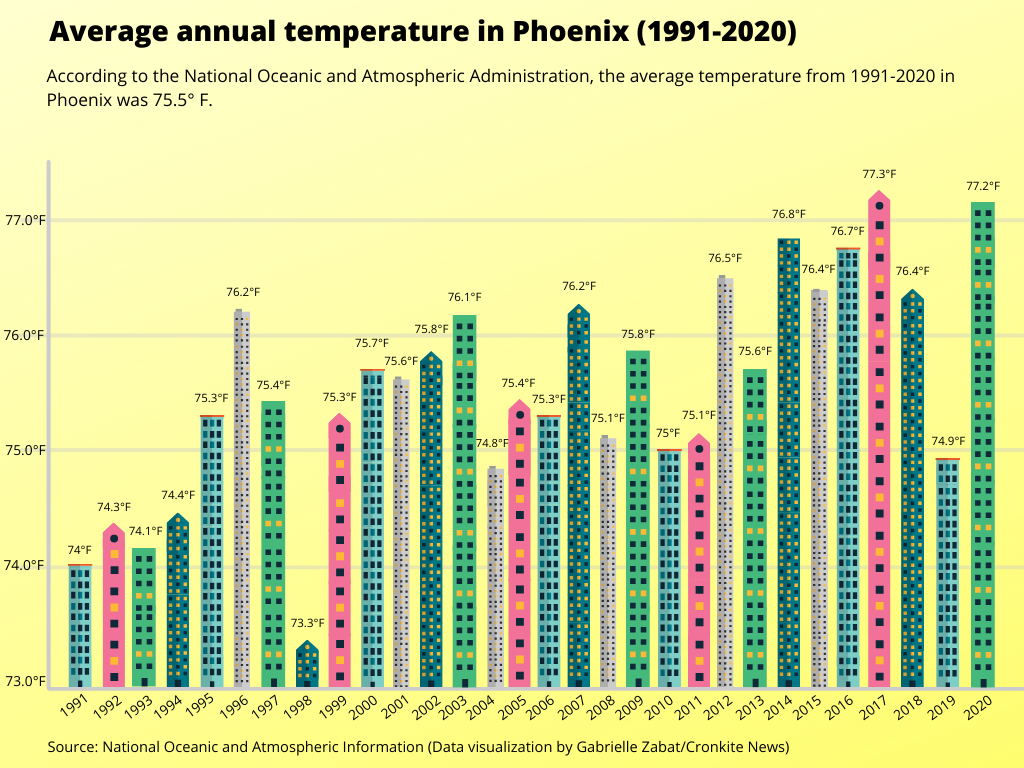

“We have actually seen average temperatures going up over the last 20 years,” Hartman said. “They have been climbing and climbing. A lot of those hard surfaces capture the heat during the day and they release it in the evening hours. So people are less resilient if you do not have the chance to cool down.”

What to do about the heat

The Arizona Department of Health Services has many safety tips to help prevent heat related illness, including limiting outdoor activity, staying hydrated, finding shade and doing outdoor activities early in the morning or late at night. However, for many people who work outdoor jobs and vulnerable populations, this is more challenging.

There are measures that cities can use to help mitigate heat associated death and illness as well.

“I think tree canopy and creating cool corridors in our city that people can navigate from their homes to stores, places to live, work and play,” Hartman said. “Creating those so I think that’s really important. We realized we need to do a lot more.”

Tejeda said strategies for outdoor workers to avoid heat illnesses go beyond having workers stay in the shade and drink more water. Markham Contracting has a heat illness prevention plan that outlines proper hydration and diet for workers to be “proactive rather than reactive,” Tejeda said.

“We also have something called a crash kit, which we give out to our foremen,” he said. “And that contains an electrolyte recovery kit that you pour into some water. And it helps the guys kind of get some good potassium salts back into their body and electrolytes in it helps them come out of very light, heat stress and kind of set them on the right path.

“It really starts having the culture be there and having the guys understand why it’s important to hydrate and prepare the day before for the next day.”