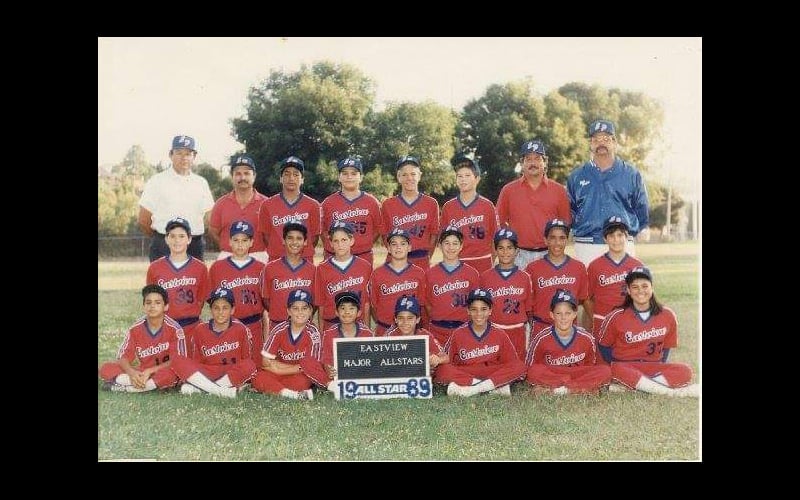

Victoria Brucker (first row, farthest right), now Victoria Ruelas, with her Little League World Series team in 1989. (Photo courtesy of Victoria Ruelas)

LOS ANGELES – Playing baseball is a beloved tradition across the Southwest. But at a young age, girls are steered toward softball, which has been deemed socially acceptable for women.

But more than three decades ago, 12-year-old Victoria Brucker and the Eastview Little League team in San Pedro, California, broke the gender barrier in American Little League Baseball. She made her Little League World Series debut in 1989, becoming the first American girl to compete in the Little League World Series. She became the first girl to get a hit and to pitch, five years after a Belgian girl became the first to play.

The Eastview Little League team finished its run with one win and two losses but marked a first for American girls in the sport.

Despite more than 30 years of barrier breakers, gender barriers still exist at the highest level of youth baseball. Only two teams with girls on the roster have won more than two games during the Little League World Series, and neither won it all. No Little League World Series team from Arizona has ever had a girl player.

But in 2021, Ella Bruning of the Wylie Little League team from Abilene, Texas, became the third girl to record multiple hits in a single LLWS game – against Washington on Aug. 20. Ella was the 20th girl to compete in the tournament.

Ella Bruning became the third girl in history to record multiple hits in a LLWS ? pic.twitter.com/5l340tnqZf

— Athlete Swag (@AthleteSwag) August 21, 2021

In the decades since her debut, Brucker, whose married name is Ruelas, has traded rounding the bases for rounding the corners of Coralville, Iowa, where she lives and delivers mail for the Postal Service. She wishes that girls playing baseball had become the norm.

“They shouldn’t have to keep saying, ‘Hey, there’s another girl,’” Ruelas said. “There should just be more girls.”

But Ruelas also remembers how she faced discrimination and taunting during her time in Little League. But she overcame it, in part due to her teammates’ support.

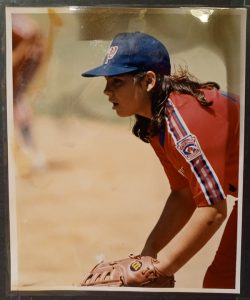

She busted her lip in tryouts, an injury that required stitches, but she was back the next day for the tryout’s second round.

“My coach told the team, ‘She’s over there with a fat lip, you’re telling me she isn’t tough enough?’” Ruelas recalled.

After that, her teammates defended her.

Players on an opposing team once called out, “‘Oh they must suck, they have a girl on their team,’” Ruelas said. “My teammates, of course, wanted to say something, to stand up to them (and) to stand up for me.”

And Ruelas held her own, too. In the game against that team, Ruelas was put on the mound, and she allowed only four hits.

“It was a good way to get back at them,” Ruelas said.

In her LLWS run in 1989, Ruelas and her team finished 1-2, and she had three runs and a hit.

Betsy Schneider, a lecturer at Arizona State University, who is also working on a project about women playing in male-dominated sports, heard similar tales.

Stories like Ruelas’ show “the negative and tribalism but also this idea of community and connection,” Schneider said. “I get goosebumps when I talk about it because it’s something so beautiful.”

Victoria Ruelas prepares to field a ball during a Little League game in 1989. (Photo courtesy of Victoria Ruelas)

As happy as Ruelas was to watch Ella Bruning and the previous barrier-breakers play and the positive coverage she received, Ruelas still felt distraught, noting that Major League Baseball’s limited women’s program isn’t enough.

MLB’s women’s program is called MLB GRIT, which is a professional workout where players are evaluated on talent. The majors also sponsor leadership events for women, but not an official league for women.

“(MLB) and white, male-organized baseball and the effort to push Black men out was as much about white manly power as pushing out girls and women is,” said Victoria Jackson, a professor of sports history at ASU. “This idea that we have an alternative sport like softball for girls doesn’t do anything to chip away at the broader ideological problem.”

Jackson and Schneider spoke to how common it is among women who’ve competed in male dominated sports to question how many gender barriers are needed to actually break the gender barrier.

“As long as it’s these one-off cases, it is just going to be a string of one-off cases,” Jackson said.

Jackson noted how in the efforts to desegregate college football, it took time for the one-offs to build into fully integrated programs, and it took until 1972 for full integration that allowed Black athletes to compete.

“Until we see multiple girls on multiple teams, it really is just going to continue to be that experience, and I don’t know if or when we will get to that point,” Jackson said.

Only three years have featured two girls competing in the Little League World Series, but none were from the same country, let alone on the same team.

“I think a lot of the women I have found are not even necessarily identified as feminists or that they want to purposely break gender barriers,” Schneider said. “Most of the people I’ve talked to just want to play.”

The girls of baseball just want to play. Schneider, Ruelas and Jackson all made it clear that baseball and softball are different sports and should not be treated as the same.

“There wouldn’t be a reason to push girls into playing one and boys to play another if they were (the same),” Ruelas said.

Schneider drew similar conclusions, and went further to note the entirety of women’s sports.

“The history of women’s sports has (had) this idea that you had to make it more gentle,” Schneider said. “Women in track couldn’t run the same distances as men, women didn’t run the marathon until the late ’70s. There’s this inherent idea that women and girls can’t handle certain things.”

With baseball players off fighting World War II, the League of Women Ballplayers was founded, and though it was a popular reimagining of America’s favorite pastime, the league was disbanded when the men returned from the war.

Jackson laid out a scenario on how the one-off cases can grow into more, and it begins with youth sports like Little League, then rising through the higher institutions, like the NCAA and MLB.

“Depending on the way youth sports (can) continue to adapt and change and be more focused on play than competitive sports, that might actually create more opportunities for girls to stick with baseball, because you have power plays when things get competitive,” Jackson said.

Taking a less competition-based focus in youth sports can help facilitate the transition for women to play more in baseball. But, there needs to be more cases of Ruelas and Bruning to fight the fight from the inside.

“(I) just want the girls to keep at it, keep fighting and keep proving them wrong,” Ruelas said.