(Illustration by Zach Van Arsdale/News21)

The Shawnee language is in danger of becoming extinct, but the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting switch to remote education gave it a chance for revival, tribal leaders say.

Years ago, the Shawnee Tribe, based in Oklahoma, created a 10-year education plan to preserve Shawnee, a central Algonquin language. In 2020 – billed as the Year of the Shawnee Language – it appeared the pandemic might derail the Shawnee Language Program.

Reluctantly, program director Joel Barnes moved the program online.

“We started just doing some virtual classes, just some lessons that I had made up then,” he said. “That’s when I came to realize: This is going to work.”

Virtual learning allowed educators to expand the reach of the language while increasing class sizes and learning opportunities. According to UNESCO, only about 100 people speak Shawnee.

Tribal Chief Ben Barnes declared a state of emergency in January 2020, saying that if the tribe didn’t preserve its language, it could mean “losing the voices of our grandparents forever … we cannot wait to act until there is a better time, more favorable conditions.”

Two Shawnee elders died of COVID-19 this past year, Joel Barnes said, and a third died of natural causes at age 99. The pandemic prompted a sense of urgency to teach younger generations the tribe’s language and culture before it’s too late.

Joel Barnes, the chief’s brother, enlisted the help of Jessica Somerville-Braun and other Shawnee educators. As an associate professor of education studies, Somerville-Braun – who lives in New York – helped craft the curriculum for the language classes.

“With this setup, you get a chance to practice the vocabulary, the pronunciation and also the meaning,” she said, which gives students more practice with the pronunciation and makes learning the language less intimidating.

The switch to virtual language classes helped educators reach members of the tribe across the country.

Somerville-Braun, whose grandmother was the last of her family to live in Oklahoma, said remote learning expanded the reach of the program.

“It’s an opportunity to connect much more closely and to learn language and culture and be part of this community in a way that wasn’t possible before these online classes started,” Somerville-Braun said.

No longer limited by proximity to a classroom, tribal members from California, Virginia and elsewhere logged on to online language classes.

In-person classes used to have 10 to 12 students per class. But online, 15 to 20 students log in for each class, and more watch recordings on the Shawnee Language Program’s Facebook page, which has more than 700 followers.

But these classes represented more than learning phonetics and piecing them together.

Raina Heaton, an assistant professor of Native American studies at the University of Oklahoma, said preserving Indigenous languages is a form of sovereignty.

“Reclaiming one’s heritage language is an important component of cultural expression, familial ties and, here in North America, national pride,” Heaton said.

Due to colonization and the cultural genocide of many Native Americans, the Shawnee are one of the few tribes that still have tribal ceremonies, Joel Barnes said.

“A lot of tribes don’t have a cultural connection. They may have their language, but they don’t have anything culturally to tie it to,” he said.

In a January 2020 announcement, Ben Barnes explained why the program would be continued online: “We cannot wait to act until there is a better time, more favorable conditions.”

The “Shawnee Language is in extremis, or to say it simply, it is in danger of being lost forever,” Chief Barnes said in a January news release. “We must act now if we are to preserve the ancestral inheritance that binds all Shawnee people together.”

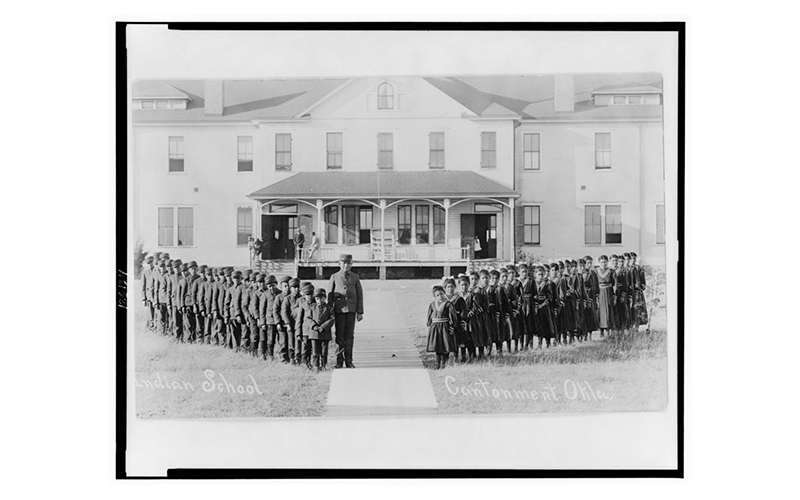

The Shawnee language became endangered in large part because federal officials forced Indigenous children into boarding schools across the country and tried to anesthetize their culture.

The Heard Museum in Phoenix exposes some of the boarding school history in Arizona, where the Phoenix Indian Industrial School opened in 1891. An overhead light shines on a mint-green barber’s chair where Native American children sat to have their long hair cut by school administrators. Words on the wall behind it tell the story of children who lost their hair, their clothes – and their identities.

Somerville-Braun said being a part of the education of new Shawnee speakers has helped her feel more connected to her culture, even though she is thousands of miles from Oklahoma.

“It was something that – because of my family’s history where we’ve been disconnected for so long – wasn’t something that I ever really sought out or felt like I could do or should do,” she said.

“I felt like this invitation helped me to understand the reason I’m disconnected is because of the forces of colonization and assimilation. And, if I wanted to be connected, I could push back against that history and those forces.”

This story was produced in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Unmasking America,” a national reporting project on the lingering toll of COVID-19 scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.