Floating in the bottom of the Grand Canyon this spring, I was traveling back in time in more ways than one. In a narrow section where the Colorado River runs deep and quiet, the “basement rocks” of the Vishnu schist offer a window onto the world as it was here 1.7 billion years ago, give or take a couple of hundred million years.

Little about the redrock walls seems different from when I first marveled at the scenery from a raft many years ago. But for the water that carries travelers through the Grand Canyon National Park, the changes have been dramatic, even though they’ve occurred over just 31 years, which in geologic time is infinitesimal.

In 1990, the big problem was managing so much water in the Colorado. Now the problem is adjusting to so little water. Drought and climate change are proving a profound challenge in the Southwest, where more than 40 million people rely on the Colorado River Basin for the water that sustains their communities and irrigates more than 3 million acres of crops. And that problem is only expected to get tougher as the region gets hotter and drier.

On my first excursion down the river in 1990, I was part of what retired NPR reporter Howard Berkes described as a “floating press conference.” That was when the primary purpose of the Glen Canyon Dam upstream was to provide cheap, convenient power to electric wholesalers serving about 1 million people in the West.

Twice-daily blasts of extra water through the dam’s turbines raised and lowered the river by as much as 13 feet a day. The surges ripped apart the beaches that recreational boaters camped on each night and disrupted the river’s ecology. Policymakers, scientists, advocates and professional river guides told the 21 assembled journalists about their growing concern about balancing dam efficiency with preserving nature in the park.

When I rafted through the canyon in May, it was clear their efforts – bolstered by decades of river research – had led to some meaningful changes in dam operations. By tinkering with the knobs controlling hydropower flows, the river’s ecological health has improved in measurable ways.

On the river, then and now

On that trip three decades ago, Dave Wegner, who led early studies of Glen Canyon Dam’s impacts for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, helped explain the problem of too much water. On a lunch break one day, he pointed to a stick jabbed into the soft, blond sand at the river’s edge. Before we got into the rafts to leave, it had disappeared beneath more than 2 feet of rising water, showing how the fluctuating river levels reflected the West’s thirst for electricity.

“We’re releasing more water at Glen Canyon Dam in response to electrical demand in the power grid,” he said.

The rush of water signaled that dam operators were responding to the region’s demand for hydropower, a daily ebb and flow. As electricity users powered up their hair dryers and coffee pots each morning, and cranked their ovens and air-conditioners each afternoon, dam operators released extra water through the turbines.

The blasts didn’t just erode the sandy beaches that rafters rely on for our campsites and picnics, they also ruined the insect hatches that provided nourishment for fish and birds and washed away plants and shrubs necessary for nesting and sustenance. The very existence of such endangered species as the humpback chub, a fish that likes warm water, was put at risk because of the torrential pulses from the chilly bottom of Lake Powell favored nonnative rainbow trout that thrive in cold water.

Gabriel Braganza filters river water into 5-gallon containers during a Grand Canyon river trip in May. About 40 million people rely on the Colorado River for water, and that demand is growing even as flows decline and climate change speeds evaporation. (Photo by Judy Fahys/Inside Climate News)

“What we’re trying to do is to figure out the dynamics of all this,” Wegener said at the floating press conference. “Are there thresholds in dam operations where we tend to accelerate erosion of these various beaches, and are there thresholds where we might tend to start to rebuild some of these beaches?”

In the years since, the Grand Canyon environment became a focus for dam operators, thanks in part to bipartisan legislation sponsored in 1992 by Rep. George Miller, D-Calif., and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. – the Grand Canyon Protection Act – and perfected over time. The law prompted an in-depth environmental assessment, ongoing scientific research, experimental water releases and, ultimately, changes in how Glen Canyon Dam was operated.

Today, the river still fluctuates, but not as dramatically as before. Steady, low flows on weekends have helped restore insects and humpback chub. Beaches for campsites are rebuilding. Birds find abundant shelter and food along the river’s edge.

But there was a lot more water flowing into Lake Powell above the dam in 1990 – about four times, on average, the volume of inflow this year.

Scott VanderKooi, who oversees the Grand Canyon Research and Monitoring Center for the U.S. Geological Survey in Flagstaff, said it’s important to keep studying the river now in light of two decades of drought and climate change.

“There’s a sense of urgency in trying to understand what is happening and how quickly and how much things will change,” he said.

Big waves and trickling tributaries

For river runners, knowing what’s happening with the water in the Grand Canyon has always been a big deal. They’re always looking out for a crosscurrent that could wallop passengers out of the boat or those Hawaii Five-O waves big enough to swallow a raft. Crystal Rapid gets more difficult in high flows, but avoiding the “Land of the Giants” holes in Hance Rapid is trickier in low water.

But water concerns took on a new meaning in May.

Sixteen of us were on a private float we organized ourselves instead of using a commercial guide service. We rowed rubber rafts and kayaks 250 miles through the national park and some of North America’s most challenging rapids – all while rapt by some of the world’s most breathtaking redrock scenery and gobsmacking geology.

We’d strapped everything we needed for more than two weeks of camping onto the boats – sunscreen, oar repair kits, rain gear, food, helmets for the big rapids, goofy costumes for party nights and cases of bubbly beverages. Our loads included 10 5-gallon jugs that, during my previous trips down the river, would have needed refilling two or three times.

Kayaker Claire Simon helps monitor progress of a chemical water treatment at Tapeats Creek, a Colorado River tributary and source of relatively clean water in the Grand Canyon. Having enough water is a preoccupation in a region coping with its 21st year of megadrought. (Photo by Judy Fahys/Inside Climate News)

In May, we refilled them six times. It’s possible this thirstiness is tied to the 17% decline since 1990 in precipitation in the canyon from January to May, which is consistent with lower moisture levels across the Southwest that have been blamed on human-caused climate change.

On the river, we noticed water wasn’t jetting from the greenery on the cliff face at springs like Vassey’s Paradise, as it had been when the floating press conference drifted past 31 years earlier. Nankoweep Creek and others were running dry.

The short hike to the Book of Worms also held a surprise. We had no trouble finding the stone panel covered with fossilized tracks the invertebrates left in the muck about 550 million years ago. But the trail to the book had many shriveled and collapsed cactus pads where lush yellow blooms had been abundant when we visited two years ago.

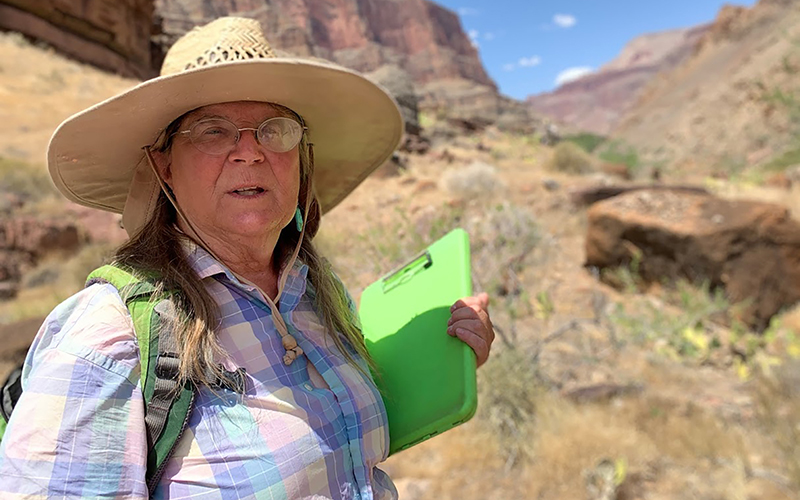

We ran into veteran archaeologist Helen Fairley across the river from Deer Creek Falls, where she and her team were snapping before-and-after photos to document long-term changes in beaches and vegetation. A scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey, she also had spotted troubling trends like these.

“You know you’re dealing with a drought when you’re seeing desert plants falling over from lack of water,” said Fairley, glancing at the desiccated cactuses all around.

Like me, Fairley, who’s been studying the canyon for decades, had also noticed the odd abundance of bighorn sheep feeding along the river’s edge. It’s not unusual to see bighorn at the river, but this time the thrill of snapping their pictures wore off because there were so many. One night, a bighorn even watched us from a rocky ridge above our camp. She seemed to glare, as if we’d elbowed her hungry family from the dinner buffet.

“Generally, they don’t come down until late summer or fall, when the water sources up high dry out,” Fairley said. “Well, this year, apparently, they don’t have water up high.”

Water became a preoccupation for us, too, even on the river.

We filled the jugs at the Phantom Ranch spigot, as usual. Then we refilled them with clean water from Tapeats Creek, chemically treating all 50 gallons to be safe. But our 5-gallon jugs ran dry surprisingly fast, and four other times volunteers from our group hauled buckets of water from the river and filtered every drop using a hand pump.

The lack of runoff this year was also visible. Runoff normally fills the river with sediment that turns the river the color of a strong mocha. But this year it was so puny – inflow into Lake Powell was about one-third of normal – that there was little sediment and the water remained unusually clear. VanderKooi said moss grew in the water as a result and kept the river green along the length of our trip through the national park.

Floating the Colorado River through Grand Canyon National Park offers a window into deep time and recent history. The needs of water users, recreationists, wildlife and the canyon’s ecology are part of an ongoing conversation made more contentious by rising demand and dwindling resources. (Photo by Judy Fahys/Inside Climate News)

This spring, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation expected the inflow into Lake Powell, the reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam, to be a fourth to a half of what’s been normal since it started filing in 1963. It’s part of what appears to be a steep decline of inflows into the reservoir, a trend that’s stepped up over the past two decades.

Pam Adams, a hydrologist for the bureau, which runs the dam, recently noted that reservoirs in the Colorado River Basin were nearly full before the current drought began. They dropped by about half in just a few years. Tree ring data showed the current drought, now christened a “megadrought” because it has lasted 20 years, represented the driest period in more than a century and one of the driest in the past 1,200 years, Adams said.

“Our challenges are not over,” she said.

Rafters and researchers study a rapidly changing river

Citizen scientists also are watching the changes as they help gather data in the Grand Canyon that ultimately will be used in setting future policies on the Colorado River.

One is river guide Maggie Oliver, who was prepping a dory at the Lees Ferry put-in, between the Glen Canyon Dam and the Grand Canyon. Oliver already had packed and stowed science kits that would travel downstream as part of a guided river trip for tourists. The kits would help gather information on bats and insects, but she was aware of bigger issues in play on the river, such as global warming.

“It’s definitely on our minds,” she said. “We’ve seen the river change; we’ve seen the flows change and the temperature change.”

Oliver, who works for Arizona Raft Adventures, the company that supported the floating press conference in 1990, recalled how on a research expedition tracking insect populations, a kind of bellwether for the ecosystem, river temperatures rose surprisingly fast as their boats made their way downstream.

Indeed, heat is at the heart of many challenges facing the basin. In a 2018 paper published in the journal Water Resources Research, a team including Colorado State University climate scientist Bradley Udall set out to understand why the Colorado River’s stream flow had declined 16.5% over the previous century when annual precipitation actually had increased 1.4% during that time. The researchers determined that warming reduced snowpacks and increased evaporation, starting in the headwaters, and could be blamed for half the streamflow’s decline.

Emma Wharton says participants in her nonprofit rafting program, Grand Canyon Youth, grasp the importance of understanding environmental change. “There’s a lot of trepidation about what is to come,” she says. (Photo by Judy Fahys/Inside Climate News)

The influential study cited five other papers that projected the trend would continue into the middle of the century, with runoff declining up to 30% by 2050, thanks to anthropogenic climate change. And the study, which compared the first 15 years of the current drought with the severe drought from 1953-68, also determined that this century’s warming was the big factor in a reduction of runoff, since actual precipitation wasn’t that much lower than in the earlier drought.

In short, no matter what way scientists contemplate the water situation in the 250,000-square-mile Colorado River Basin, human-caused global warming is having significant impacts throughout the region.

A lack of forage on the range is forcing ranchers to reduce herds. Tinder-dry vegetation has increased the risks, costs and extent of wildfires. Heat-related deaths are increasing. Less snow and snowmelt from the mountains means less water flowing through Glen Canyon Dam to produce carbon-free hydroelectric power, which, in turn, might create more demand for fossil fuel energy to make up the difference.

Longer droughts, more evaporation, precipitation changes, earlier runoffs, lower streamflows – they’re all expected in the Colorado River Basin of the future, especially if projections are correct that more greenhouse gasses will result in temperatures that could be as much as 5 to 7 degrees higher throughout the Mountain West.

These are unavoidable concerns for the members of Grand Canyon Youth, said Emma Wharton, who leads the Flagstaff nonprofit for ages 10 through 19. She also can imagine a time soon when water levels dip so low on Lake Powell that hydropower production falters at Glen Canyon Dam. To avert such an issue, the Bureau of Reclamation last month announced plans to release water held in reservoirs upstream, which also are low.

“There’s a lot of trepidation about what is to come,” Wharton said. “This generation is really going to have a lot of challenging decisions to make moving forward, but I also see the hope in the love and care that our alumni and our participants have for these places and that there is a lot of joy there at the same time.”

People who rely on the Colorado River are coming to grips with the fact that too much water is an easier problem to solve than too little.

High stakes for the river – and the people it supports

Considering how that floating press conference helped inspire changes to protect the Grand Canyon, there’s reason to believe that scientific data gathered over three decades then can help bring the kind of transformations that will be necessary to keep the Colorado River healthy for future rafters, fish, plants and sheep.

Yet, my reporting on the issue over those decades also gives me pause. That’s because the common refrain is that everyone – the seven states in the Colorado River Basin, the 39 Indigenous tribes and the hundreds of thousands of recreational users – must work together to address the uncertainties of Colorado River water and the shortages we’ve started seeing. In a society so much bigger than a rubber raft, it’s not clear that we’re up to the challenge of collaboratively managing a shared resource in such challenging times.

On the Colorado River, cooperative agreements among water users, one hammered out in 2007 and another in 2019, offer some hope that it’s still possible to stay the course and continue protecting the ecological resources in the Grand Canyon. But the stakes are getting higher, too. A variety of strategies, including releases from upstream reservoirs to protect Lake Powell and water conservation, already have been implemented in California and Nevada. And, by the end of August, the Bureau of Reclamation is expected to start reducing water to farmers in Arizona.

But at the same time, the Upper Basin states – Utah, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico – are planning new dams and pipelines for the Colorado River water they have let downstream states use for a century. It’s water those Upper Basin states were granted under the 1922 Colorado Compact, when river flows were strong. All of the states, both in the Upper and Lower Basin, want more water to accommodate growth just as climate change promises a future that’s drier and hotter.

There are hard realities foreshadowing brutal choices. The needs of growing cities and established farmers, the demands of power producers and tribes, the protection of endangered species and the environment seem destined to collide in the long-term. And, on the Colorado River, as with most of the water in the West, the most immediate human needs – water, food, electricity, recreation – usually have prevailed.

I recall something Fairley told us deep in the canyon in May.

“We have to figure out how to keep people with enough water to drink and to sustain human life and society,” she said. ”At some level, it does become kind of a preeminent concern over every other issue.”

Fairley hopes to see those decisions made intelligently and strategically – and with the help of science – so that the Colorado River can continue sustaining life and the Grand Canyon far into the future.

Perhaps that’s a lesson that’s easiest to comprehend in a raft floating between the steep walls of the quiet canyon, even in a flash of geological time.

The story was produced from recordings made by retired NPR reporter Howard Berkes. It is part of ongoing coverage of water in the West, in collaboration with InsideClimate News and Colorado public radio station KUNC.