A drought, a virus and a landslide – these concurrent crises have worsened the food insecurity of Northern California’s Yurok Tribe and spurred some members to explore their own solutions.

Their reservation, nestled between the Pacific Ocean and the redwoods of the Klamath Mountains, was declared a rural food desert by the USDA in 2017. The situation worsened when the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with severe drought and a crumbling highway, slammed the reservation and nearby Indigienous communities.

Sammy Gensaw, 26, grew up paddling redwood canoes on the Klamath River and driving the winding mountain roads of California’s North Coast. Since he was 10, Gensaw has been advocating for his people – and the food provided by the river and its valley – at government meetings and with nonprofit groups.

Giving Indigenous communities the means to feed their families is a responsibility Gensaw wants to take on, starting with giving people access to healthful food choices.

“While people are dying here in the Klamath Basin – where people are getting sick and getting diabetes and not being able to provide for themselves – this is what we’re facing,” Gensaw said. “It’s not just the environment. We’re facing a whole system that needs to be changed.”

Indigenous people suffer from negative health disparities, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says makes them particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Health inequity further exacerbates disparities in food, housing and income. In response, the federal government, through the CARES Act of 2020, allocated $8 billion to be directed to Native American tribes and organizations.

CARES Act funds and financial support from nonprofits have subsidized Indigenous communities’ efforts to achieve food sovereignty. For the Yurok Tribe, that has meant a pivot from traditions such as fishing, which is becoming unsustainable as the West gets hotter and drier, toward gardening. Some tribal members are working to grow their way out of a food desert.

The CDC granted California tribes more than $19 million in CARES Act funds to address health needs and related issues; only Alaska received more. The Yurok Tribe, the largest in the state, with more than 5,000 enrolled members, received about $1 million – the largest sum from the CDC to any California tribe. The Yurok Tribe received more than $32.7 million in CARES Act money from the Coronavirus Relief Fund.

The tribe used $490,000, according to property tax records, to buy 40 acres of land, which was originally a part of their ancestral home.

The tribe’s Food Sovereignty Division plans to create “food villages” on the 40 acres, manager Taylor Thompson said. The daisy-covered hills, grassy meadows and redwoods would become a communal garden and commercial kitchen, with small homes for workers to create a self-sustaining food system that can withstand a crisis.

These food villages would provide healthy food options in an area with limited food access. The reservation’s population is 836, according to the Census Bureau, and the nearest supermarket is more than 40 miles north in Crescent City.

“The accessibility of the nearest supermarket from some of these communities is like an hour and a half drive one way,” Thompson said. “So it’s just a real barrier for people to be able to have access to fresh produce or sufficient food choices for them to be able to have healthy, well-rounded nutrition.”

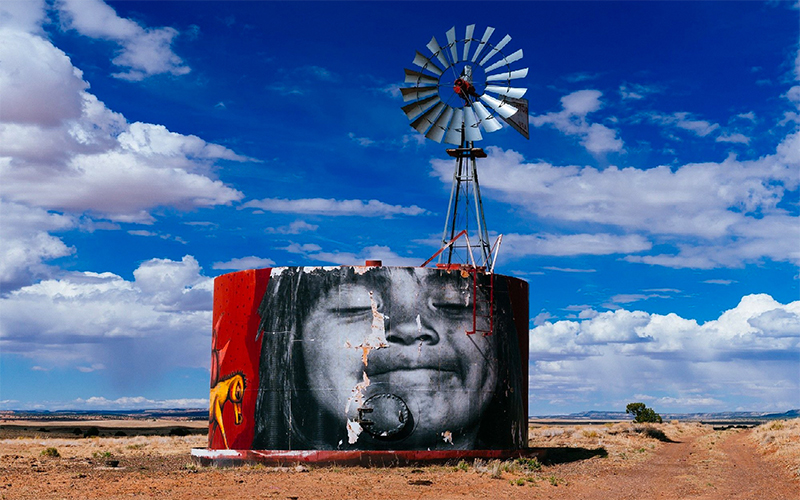

Members of the Ancestral Guard paddle redwood canoes onto the Klamath River, which provides eels, sturgeon and crab in addition to salmon. Yurok people also gather acorns, berries and other foods on the riverbanks. (Photo by Beth Wallis/News21)

Growing generational knowledge

Gensaw co-founded the organization Ancestral Guard, which became a nonprofit in 2015. The organization teaches Indigenous youth farming and fishing, as well as provides families a sustainable way to obtain and produce food.

He said it’s particularly important to root food sovereignty in younger generations, who one day will become elders who pass on their knowledge.

“When we say sovereignty, we want our people to be able to make healthy decisions,” Gensaw said. “We want our people to be able to say, ‘Yes, I can grow a garden. Yes, I have the resources to do so. And yes, I’m going to invest these resources back into my community,’ because recreating these systems of reciprocity between Indigenous people and the land that we all live in (and) depend on, these have been broken by years and years of genocide.”

U.S. 101 is the main road through the reservation. Along the highway, on the western edge of the reservation, sits the tribal-owned Pem-Mey Fuel Mart, one of two gasoline stations on the reservation and the only source of food available to purchase. The fuel mart – which also provides WiFi for an area with spotty service – is where Gensaw submitted the application for the grant that funded Ancestral Guard.

If Yurok living on the reservation want to go to the nearest grocery store in Crescent City, it takes more than an hour even without traffic. A landslide in February along a 3-mile stretch of U.S. 101 between Crescent City and Klamath, known as Last Chance Grade, stretched that drive to two hours. While repairs continue, the grade is closed from 8 a.m. to noon Mondays through Thursdays, and 8 a.m. to noon and 3 to 7 p.m. Fridays.

Last Chance Grade is so prone to landslides that locals refer to the patchwork repairs on the two-lane highway as “$1 million Band-Aid.” Since 1997, the California Department of Transportation has spent $85 million on maintaining the road, according to the Last Chance Grade Project, which began surveying the area in 2015 and is dedicated to finding a permanent solution.

The project estimates that construction of an alternative route could be completed from 2031 to 2039 but would come at a steep cost, with alternative routes costing between $295 million and $1.1 billion. A 2018 study found that a one-year closure of Last Chance Grade would reduce business output by $456 million, accrue $236 million in travel costs and require residents to make a 320-mile, six-hour detour.

Gensaw said COVID-19 also highlighted the food insecurity in the Yurok Tribe and nearby Indigenous communities. Although the Ancestral Guard was in the works before 2020, it began its five-year food sovereignty effort during the pandemic, starting with the Victorious Gardens Initiative. It launched a 10-row community garden near a bend in the calm Klamath River and has since expanded into 3-by-6-foot garden boxes at 30 homes on the reservation and in Klamath and Crescent City.

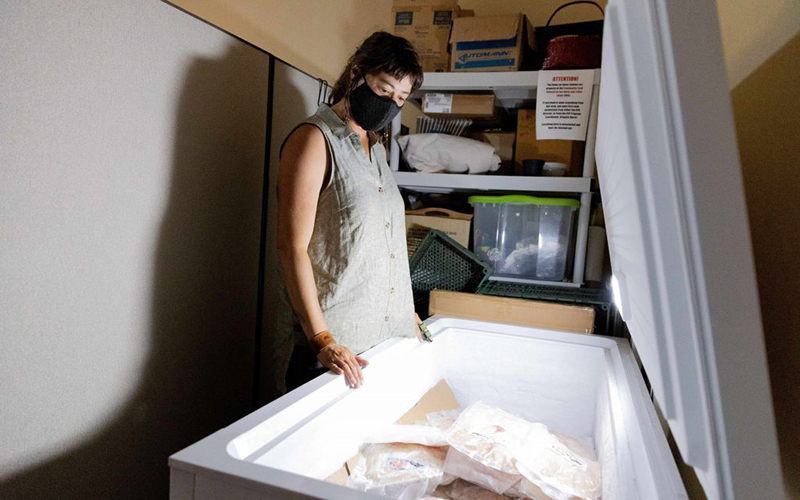

Drea Lanctot with the Del Norte County and Adjacent Tribal Lands Community Food Council checks a freezer full of salmon and other local fish. The council partners with local fishermen, whose businesses plummeted during the pandemic, to provide protein to people in the area. (Photo by Beth Wallis/News 21)

Balancing food security, traditional practices

The Yurok traditionally are fishermen – for salmon, eels, sturgeon and crab – but they also gather acorns, berries and other foods. The Klamath, historically teeming with Chinook salmon, runs south through the reservation from Oregon. Del Norte and Humboldt counties are experiencing severe and extreme drought, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System.

That led Gensaw to start the Victorious Garden Initiative and show, as he says, that fishermen can farm. Teaching a young person how to garden not only will provide a stable source of food, it will create a culture of gardeners and farmers.

“We’re not just growing food, we’re not just giving it to people,” Gensaw said. “We’re trying to revitalize the idea that these gardens are a piece of our culture, because often in Indian Country, traditions and cultures get muddled together. In reality, these traditions are things that our fathers have done or our grandmothers have done and their grandparents have done and we’ll continue to teach our children.”

The historic drought has allowed the Ceratonova shasta parasite to rapidly spread among the salmon, killing off juveniles. Although these parasites naturally are present in river water, experts say the ongoing drought and a dam upriver (which is scheduled for removal in 2023) have heightened the threat by contributing to the Klamath’s low level.

The drought and pandemic have harmed tribal members financially. Jonathan Jackson grew up in the late 1980s and early ’90s, fishing the Klamath by night with his parents and brother and processing the catch at home during the day. In 2001, he started commercial fishing and later established his own business, Pacific Native Fisheries.

When the pandemic began in March 2020, he found that his regular customers – restaurants and fish markets – weren’t buying. Jackson couldn’t afford to stop fishing, so he began making home deliveries.

“When the pandemic hit and everything shut down, we lost all of our markets and then all the big buyers also quit,” he said.

Jackson doesn’t live on the reservation or in the area. He fishes down in the North Bay, he said, in part because of the drought’s effect on the Klamath. Although it’s many miles south, near San Francisco, the North Bay area still feels the effects of the river’s environmental issues. Because salmon travel south, Jackson said, their low numbers in the Klamath River mean fishermen to the south are limited by the government on how many salmon they can catch.

Crabbing season also yielded a low harvest; last season was the worst he has seen, Jackson said. His first pull yielded 400 pounds of crab, and at $3 a pound he made only $1,200. In a normal season, the first pull would be 7,000 pounds of crab, worth $21,000.

Jackson got through the pandemic and reduced fish harvests with help from Fresh Catch: North Coast Fresh From the Sea, a program run by the Del Norte County and Adjacent Tribal Lands Community Food Council. The council received a COVID-19 relief grant from Catch Together, a nonprofit that helps fishing businesses across the country.

The food council bought salmon from Jackson and other businesses to be used in its food boxes distributed by the food councils run by Pacific Pantry. The program also delivered fish meals to senior centers and packaged fish for meal-distribution centers, including some serving Indigenous people.

“With this crab season being as poor as it has been, it really saved me,” Jackson said of Fresh From the Sea. “Otherwise I wouldn’t have made my mortgage payment this year.”

A highlight of the program was its ability to address two problems, said Drea Lanctot, the council’s community food program coordinator.

“As the pandemic sort of showed us our supply chains, we’re trying to keep fish local, so that helps support small fishermen, (and) it gave our tribal elders and community members access to the nutrient dense seafood, local protein,” Lanctot said.

Although the Yurok traditionally fish, they’ve turned to growing foods for a healthier future.

“We’re really just learning what it is to be farmers, really, because we’re all fishermen,” Gensaw said.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Unmasking America,” a national reporting project on the lingering toll of COVID-19 scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.