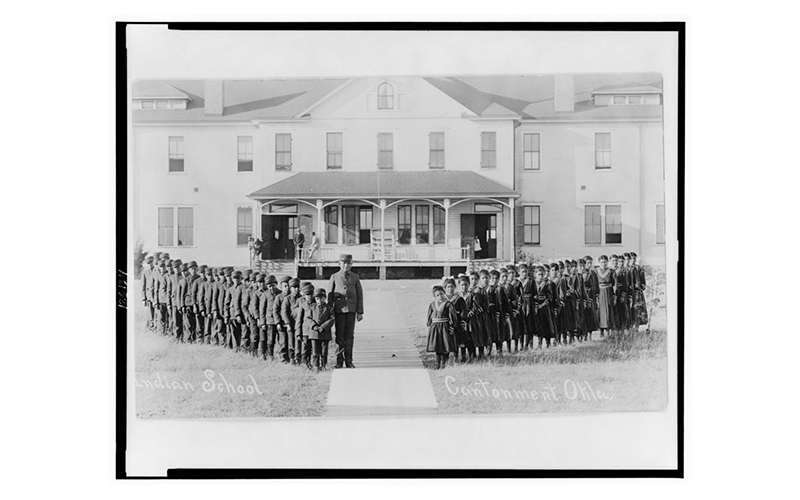

PHOENIX – When the Phoenix Indian School was established in 1891, the top federal administrator considered it a budgetary win to send Native American children to boarding schools to enforce assimilation into white society.

“It’s cheaper to educate Indians than to kill them,” Indian Commissioner Thomas Morgan said at the opening of the school.

The true cost of Indigenous boarding schools in the United States and Canada, and the abuses Native Americans endured in them, continues to be revealed. With nearly 1,000 bodies in mass graves discovered this month on the grounds of Canadian boarding schools amid their ongoing investigation, and Secretary of the Interior Deb Halaand’s recent pledge to investigate past abuses in the U.S., Arizona’s Indigenous boarding schools are facing fresh scrutiny.

Rosalie Talahongva, who curates the Phoenix Indian School Visitor Center, said she and many of her Hopi relatives went to school there.

“If you ask, was that voluntary, I would ask you, is it voluntary when there isn’t any other option?” Talahongva said.

The Phoenix Indian School closed in 1990 by order of the federal government. But a handful of Indian boarding schools remain in operation.

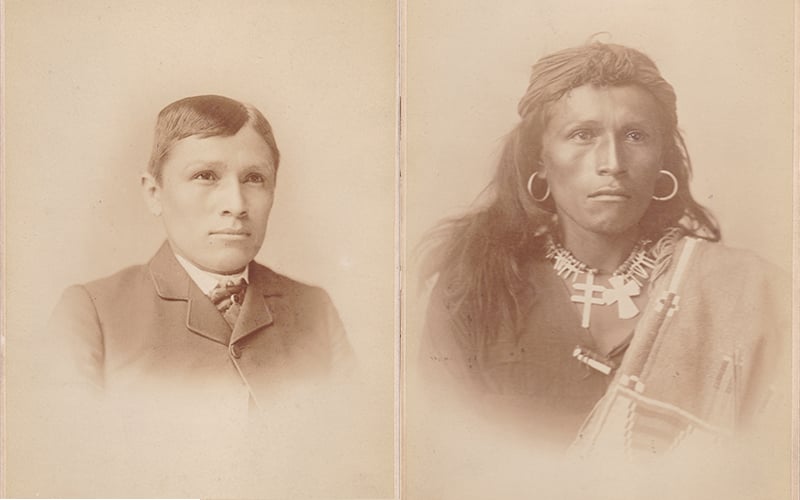

“Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt had a lot to do with the structure of these boarding schools,” Talahongva said, referring to the founder of the influential Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. “His idea was ‘Kill the Indian, save the man.’ So the whole destruction, annihilation of Indian identity – Indian culture was to be destroyed at these federal boarding schools.

“There were many children that were just forcibly taken away from their families and made to come to boarding school.”

By 1900, 20,000 children were in Indian boarding schools. By 1925, that number had more than tripled, according to Boarding School Healing.

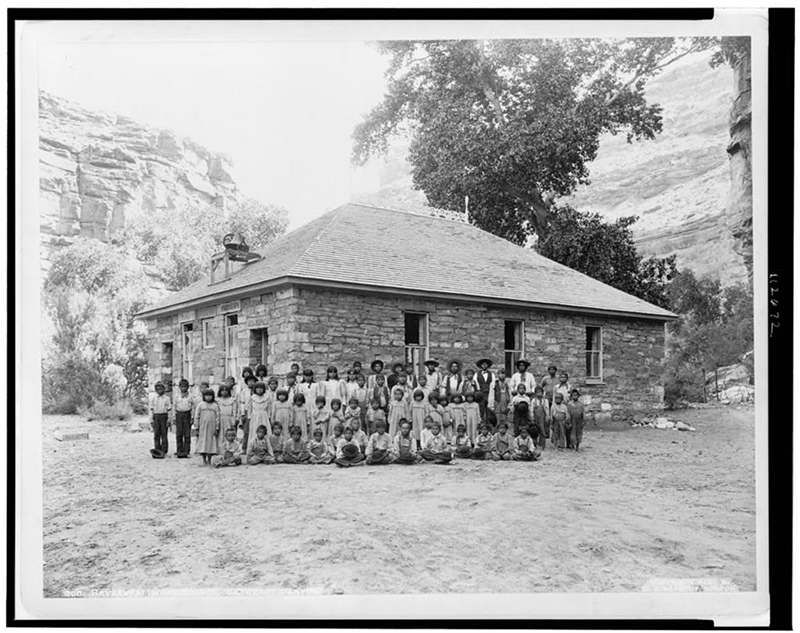

Children at Havasupai Indian School in Cataract Canyon, Arizona, in 1901. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Students were stripped of everything related to Native life. Their hair was cut short, they had to wear uniforms, and students were punished physically for speaking anything but English. Contact with family was discouraged or prohibited. Survivors have described a culture of pervasive physical and sexual abuse at the schools. Food and medical attention often were scarce and led to many deaths, according to The Atlantic.

Some of the schools were operated by the Catholic Church. The Atlantic reports “about one-third of the 357 known Indian boarding schools were managed by various Christian denominations” under the 1819 Civilization Fund Act.

The Catholic Diocese of Phoenix did not respond to requests for comment.

The operation of the long-shuttered schools will face new inquiry under the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative announced Tuesday by Haaland. The department intends to identify boarding school facilities and burial sites across the country and review enrollment lists.

The announcement came after the discovery of the remains of 215 children on the grounds of Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada. More graves have already been found in Canada. The Cowessess First Nation found 751 unmarked graves at the site of the former Marieval Indian Residential School, the Washington Post reported Thursday. The Sioux Valley Dakota Nation is working to identify a series of unmarked graves at the former Brandon Residential School in Manitoba, according to Chief Jennifer Bone. So far, 104 possible bodies of Indigenous children have been discovered on or around the school’s property.

Chiricahua Apaches at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, after four months of training in the late 1800s. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

“It will be hard to look back on that past, but it’s time that it was acknowledged,” Talahongva said. “The atrocities that happened here need to be acknowledged.”

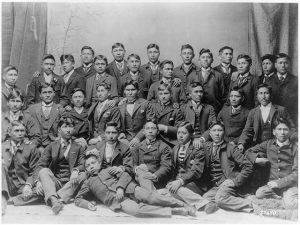

According to the Heard Museum in Phoenix, four off-reservation Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools are still in use: Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon, Sherman Indian School in Riverside, California, Flandreau Indian School in Flandreau, South Dakota, and Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Oklahoma. However, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition told Reuters more than 70 schools still operate in the U.S.

Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna in New Mexico, calls herself a product of “horrific assimilationist policies” in the U.S.

“I come from ancestors who endured the horrors of Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead; the same agency that tried to eradicate our culture, our language, our spiritual practices, and our people,” she said Tuesday in remarks to the National Congress of American Indians.

Marsha Small, a Montana State University doctoral student, has been using ground-penetrating radar to locate unmarked graves at the Chemawa Indian School cemetery in Salem, Oregon. So far, she has found 222 sets of remains at the school, which remains in operation.

“Until we can find those kids and let their elders come get them or know where they can pay respects, I don’t think the Native is going to heal, and as such I don’t think America is going to heal,” Small told Reuters.

One researcher told Reuters they believe that as many as 40,000 children may have died in Indian boarding schools in the U.S.

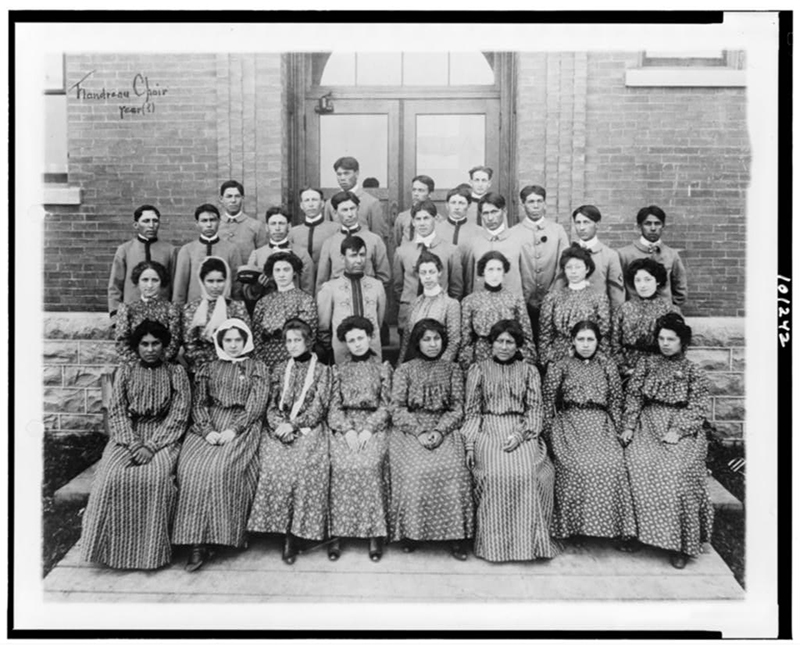

Male and female choir members pose at Flandreau Indian School in South Dakota, circa 1909 to 1932. The off-reservation school remains in operation. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

“We must uncover the truth about the loss of human life and the lasting consequences of the schools,” Haaland said in remarks about the new Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. “This investigation will identify school facilities and sites, the location of known and possible burial sites located at or near school facilities, and the identities and tribal affiliations of children who were taken.”

The initiative will proceed in several phases and include the identification and collection of records and information related to the Department of Interior’s own oversight and implementation of the Indian boarding school program, as well as conducting consultations with Tribal Nations, Alaska Native corporations and Native Hawaiian organizations, according to a press release from the Department of the Interior.

“I know that this process will be long and difficult,” Haaland said. “I know that this process will be painful and won’t undo the heartbreak and loss that so many of us feel, but only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud to embrace.”

Cronkite News reporter Julia Sandor contributed to this report.