Declining levels at the second-largest reservoir in the U.S. have spurred officials in Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico to search for ways to prop it up.

Lake Powell on the Colorado River is dropping rapidly amid one of the southwestern watershed’s driest years on record. It’s currently forecast to be at 29% of capacity by the end of September – the lowest level since the reservoir first started filling in 1963. Its sister reservoir downstream on the Colorado River, Lake Mead, also is approaching a record low this year.

The amount of water flowing to Lake Powell since October has been less than what the river delivered during the same period in 2002, the driest year on record. Total reservoir storage in the Colorado River basin is projected to be at 39% of capacity by the end of September.

“Our team of Colorado River hydrology experts have been closely monitoring conditions and analyzing the impacts on river operations, and are very aware of the daunting projections,” Colorado Water Conservation Board Director Rebecca Mitchell said in a statement.

Federal projections for the reservoir are prompting water officials to begin strategizing ways to keep Lake Powell from declining to a level where hydroelectric power generation is not possible. In a statement, the Upper Colorado River Commission announced it will begin developing a drought response operations plan, a measure outlined in a 2019 agreement. Earlier this year the reservoir’s declining level triggered monthly calls among the Upper Basin states and mandated a wider range of modeling.

The commission is made up of officials from Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Utah and the federal government.

“Colorado stands ready to work with our neighboring Upper Basin states to implement all aspects of the Drought Contingency Plan if conditions warrant,” Mitchell said.

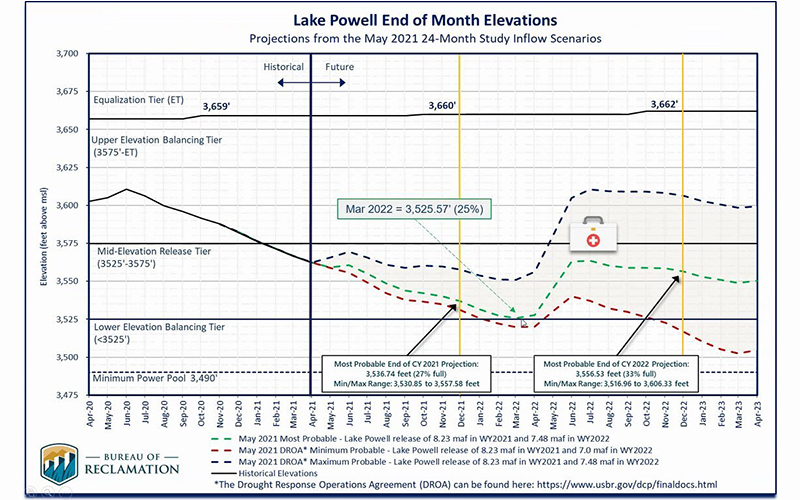

The 2019 drought contingency plan calls for operational changes to Glen Canyon Dam to preserve the lake’s level if it is projected to decline past a critical threshold, identified in the plan as 3,525 feet above sea level.

While some models show it’s plausible the reservoir could dip below that point by next spring, the most probable forecast shows Lake Powell staying narrowly above that threshold. Nevertheless, Upper Basin leaders say they can’t just wait to see how bad things get.

“The parties feel it is prudent to begin the development of a plan now, rather than waiting until we hit the absolute 3,525-foot threshold,” said Amy Haas, the Upper Colorado River Commission director.

An Upper Basin drought response plan could include water releases from upstream reservoirs, including Blue Mesa, Navajo and Flaming Gorge, to prop up the declining pool at Lake Powell. The details of how those releases would be made aren’t known.

“This is all new territory,” Haas said.

In their statement, the Upper Colorado River Commission also acknowledged Interior Secretary Deb Haaland could step in and take “emergency action” if conditions worsen. Haaland would need to consult with Colorado River basin states before taking any action. The plan doesn’t define what constitutes an emergency at a federal reservoir, and leaves the authority to declare one up to Haaland.

The Upper Colorado River Commission’s announcement comes on the two-year anniversary of the drought contingency plan’s signing ceremony at Hoover Dam in 2019.

A May 2021 forecast from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation shows Lake Powell dropping over the next year. (Image courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation)

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC in Colorado, and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.