Sparse monsoon rainfall last summer and spotty snowfall this winter have combined to dramatically worsen the drought across the West in the past year, and spring snowmelt won’t bring much relief.

Critical April 1 measurements of snow accumulations from mountain ranges across the region show that most streams and rivers will once again flow well below average levels this year, stressing ecosystems and farms and depleting key reservoirs that are already at dangerously low levels.

As the climate warms, it’s likely that drought conditions will worsen and persist across much of the West. Dry spells between downpours and blizzards are getting longer, and snowpack in the mountains is starting to melt during winter, new research shows. The warming atmosphere may also be suppressing critical summer rains from the western monsoon, a seasonal shift in wind direction often accompanied by precipitation.

A year ago, when California and Colorado experienced their worst fire seasons on record, drought conditions spanned about half the West, and no areas categorized as “extreme” or “exceptional.” But going into this year’s dry season, about 90% of the region is now in drought, with 40% in those two most severe categories.

At the end of March, the U.S. Drought Monitor showed exceptional drought spreading across roughly half of Nevada, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico, and extending up to northern Colorado. Utah was persistently dry from January 2020 through January 2021, with some welcome snow piling up in just the past few weeks, but too little and too late to stop the state’s steady drying. California’s snowpack is about half of average, according to that state’s April 1 snow survey.

“Everything is looking below to much below average,” said Cody Moser, senior hydrologist for the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. Although everyone is hoping for a wet spring, he said, “we’re not holding our breath for something like that.”

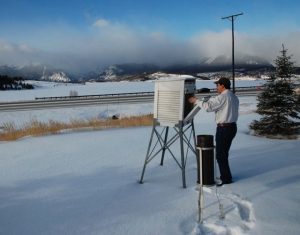

Dave Fernandez, an engineer for Denver Water, takes a daily weather reading, tracking new snowfall, temperature and moisture near Dillon Reservoir, a key drinking water source for millions of people around Denver. (Photo by Bob Berwyn/Inside Climate News)

Forecasters expect this year’s annual flow into Lake Powell, a key Colorado River reservoir that helps distribute water to 40 million people and vast croplands in the Southwest, will only be around 45% of normal.

New studies show lengthening dry spells, earlier snowmelt

This year’s parched conditions aren’t surprising to climate scientists who study the region. Nearly all recent research suggests that the West is experiencing what climatologists call aridification – decades of drying with rare relief from occasional wet years.

Research published this week by the American Geophysical Union analyzed daily temperature and precipitation readings collected from 1976 to 2019 at 337 weather stations from North Dakota and Texas to the West Coast.

The analysis showed that, across the West, the longest dry spells between measurable precipitation are increasing by 2.4 days per decade, while precipitation is declining about 0.09 inches and temperatures are increasing at 0.36 degrees Fahrenheit every 10 years.

The hardest hit is the desert Southwest, where average dry spells increased by 50% – from 31 to 48 days – during the 45-year study period, and total annual precipitation declined by 0.75 inches per decade.

Bill K. Smith, who studies how drought in the Southwest affects plants and is an author of the University of Arizona study, said those trends have accelerated since 2000. The new study and other research show that changes in the timing and intensity of rainfall are likely to disrupt plant communities, he said. Species that grow quickly after an intense downpour and can survive dry spells in dormancy are likely to replace those needing a steadier supply of moisture.

“It may not necessarily always be a story of desertification, but there will be major shifts in types of ecosystems,” Smith said. That could lead those drylands to emit more carbon dioxide than they take up, which could further speed global warming.

Early snowmelt could disrupt ecosystems and water management

One reason that less moisture is trickling down from mountains to arid landscapes below is that more snow is melting during winter, when it should be piling up, as shown in another recent study published in Nature Climate Change. That research, led by University of Colorado, Boulder climate scientist Keith Musselman, is the first to compile a long-term data record from 1,065 automated weather stations in the Western United States and Canada.

One-third of those stations showed that snowmelt is increasing throughout the winter, but especially in November and March. This year, the winter snowpack in Colorado was already in steep decline on April 6, when it typically is at its peak.

The findings show that the Western snowpack is more sensitive to warming than suggested by the commonly used measurement of the snow’s water content, Musselman said, and more winter snowmelt will complicate water resource planning. Water managers around the West have historically relied on the April 1 snowpack measurements to decide how much water to store or release from reservoirs, and how much will be available for seasonal irrigation.

The findings bolster projections that global warming will disrupt a water cycle that’s been relatively stable for at least the past few hundred years, said snow scientist Jeff Deems, part of the research team at the Western Water Assessment.

“At a basic level, this study helps quantify something you suspected anecdotally,” he said. “We’ve grown up in a world in which snowpack has been a reliable reservoir, but it’s not that way anymore.”

The research shows that the widely used measurements from snow-sensing stations and manual surveys don’t tell the whole story of how global warming is changing the snowpack, Deems added.

“We can’t rely on history anymore to tell us what is up there,” said Deems, co-founder of a company that does aerial snow measurements. Keeping up with the rapid changes warming is making to the water cycle requires more emphasis on broad-scale measurements of snow from planes and satellites, he said.

The April 1 snowpack readings worked well in the past, Musselman said, but when you add in new and rapidly changing factors like winter snowmelt, “you’re eroding your predictive capacity.”

Big impacts trickle down from snow melting in winter

Early snowmelt can raise winter soil moisture, which could “prime the pump for an extreme response, something like a rain-on-snow flood event,” Musselman said. Wetter cold-season soils may also emit more carbon dioxide, and increasing winter runoff can wash more pollution into rivers, worsening water quality, he said.

In Yosemite National Park’s Tuolumne Meadows, Jessica Lundquist, with the Mountain Hydrology Research Group at the University of Washington, found that 2017 storms that delivered record-setting snowfall to California’s Sierra Nevada also brought rain and extremely low temperatures, which formed ice layers within the snowpack that left a “bathtub ring of damage” to trees encased by the ice. Similar frozen layers in the snowpack can also make it harder for animals like bighorn sheep to find food.

Winter rain and snowmelt, combined with extreme temperature swings, can cause more damage to houses and roads when water seeps into small cracks and widens them as it refreezes, crumbling pavement and tearing gutters off homes, she said.

Oregon State climate scientist Phil Mote said the changes to snowpack and precipitation documented in the recent studies could put some places more at risk of having both extreme floods and droughts within the span of a few months.

Climate models don’t suggest annual precipitation will change that much in the Northwest. But it’s likely that it will come in more intense bursts, including from wetter atmospheric rivers that have longer dry spells between them, as shown by Smith’s work at the UArizona.

“Winter storms in a world that’s a few degrees warmer means that, within a few month period, there is a greater likelihood of both winter flooding and summer drought,” Mote said. A 2015 drought cost Oregon agriculture about $700 million and lowered river flows to spur blooms of potentially toxic river algae that challenged municipal water managers, he said. That drought also primed forests for what was then the Pacific Northwest’s most destructive wildfire season.

“A lot of these issues tie back to snowpack in some way,” he said.

One of the clearest impacts of increasing drought, precipitation variability and heat in the West is on forests, Smith said.

“What’s consistent is, the mortality signal is on the rise,” he said. “We know some of the big trees, some particular species, are dying.”

Lani Tsinnajinnie, an assistant professor in community and regional planning at the University of New Mexico, said the recent research helps summarize and confirm observations from around the Southwest, including her home community of Na’Neelzhiin in the easternmost part of the Navajo Nation Reservation.

“It helps us better understand the changes we are noticing,” she said, emphasizing that precipitation and runoff seeping into groundwater recharges springs that are important water sources for communities throughout the Southwest. The changes in the snow-water cycle will also affect important plant resources, such as piñon trees, she said.

“Piñon-juniper forests are really dependent on winter soil moisture,” she said. “They are in that snow transition zone, and those forests that are more vulnerable to loss of snowpack.”

If there’s not enough winter moisture, she said, piñon seeds can’t sprout, so the forests don’t regenerate.

“It’s pretty scary for me and for a lot of people here in the Southwest,” she said. “The piñon nuts are part of our diet, part of our informal economy, and we are a little worried and concerned.”

Weak snowpack is deepening drought from last year’s ‘nonsoon’

The early melting of the snowpack isn’t the only factor contributing to this year’s drought, as what water does trickle down from the mountains is being sucked up by soils left parched by the failure of the Western monsoon last summer.

A 2017 study published in Nature Climate Change projected that precipitation from those seasonal thunderstorms could drop by up to 40% if the atmosphere continues to warm at its present pace through the end of the century.

Last year, when that vital rainy season never materialized, some meteorologists joked darkly about the “nonsoon.” The biggest story this year could be “how dry the soil is,” said Jon Meyer, a research climatologist at the Utah Climate Center. Land left dry last summer will have a sponge effect on the meltwater that does trickle down from the mountains.

Although there were a few weeks of decent precipitation late in the winter, and the worst-case scenario of record-low snow didn’t materialize, the situation for runoff and reservoirs remains dire.

Models by the Utah Climate Center suggest drier times look likely for at least three or four years, but Meyer said he’s not ready to call it a megadrought yet. Still, he said the current 20-year dry spell across the West is having a big impact on water supplies.

“We don’t need a megadrought to have mega-impacts,” he said.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River Basin and water in the West. It was produced by Inside Climate News and distributed by public radio station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado.