The Colorado River is one of the most engineered river systems in the world. Over millions of years, the creatures that call the river home have adapted to the natural variability of its seasonal highs and lows. But for the past century, they have struggled to keep up with rapid changes in the river’s flows and ecology.

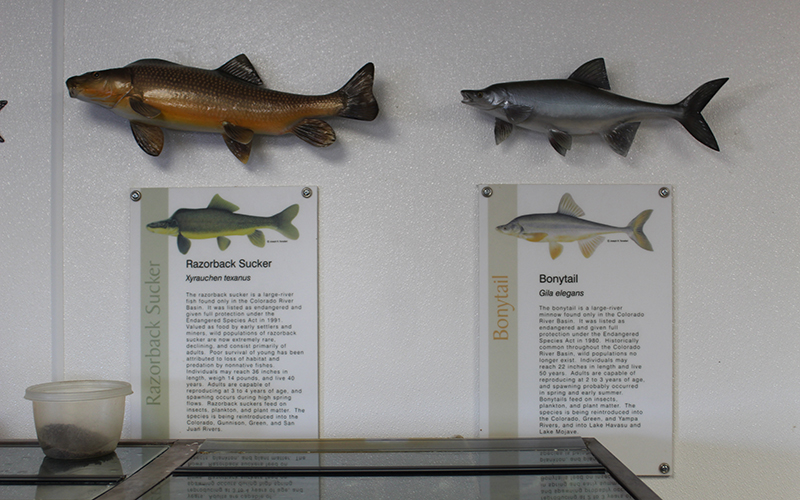

Dams throughout the watershed create barriers and alter flows that make life hard for native fish. Toss in 70 non-native fish species, rapidly growing invasive riparian plants and a slurry of pollutants, and the problem of endangered fish recovery becomes even more complex. The river system is home to four fish species listed as endangered: razorback sucker, Colorado pikeminnow, bonytail and humpback chub.

For decades, millions of dollars have been spent on boosting populations of the river’s fish species on the brink of extinction. Although scientists are learning what helps some species survive in the wild, other species still are struggling.

‘Darling little divas’

Much of the work of keeping these fish from extinction is conducted in a handful of hatcheries across the West. One of them is the Ouray National Fish Hatchery, which sits along the Green River in northeastern Utah. It’s a squat, unassuming building next to a series of ponds where two of the river’s endangered fish – the bonytail and razorback sucker – are raised.

Inside, the room is filled with aqua-colored tubs of water. A pipe feeds each tub with fresh water and creates a whirlpool, simulating a river’s flow. Above the tubs, lights automatically dim up and down to give the fish some semblance of a sunrise, high noon and sunset.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Matt Fry peers into one of the tubs and warns not to do it too quickly to keep from stressing them out.

“When they see you, they’ll scatter,” he said.

Fry is the acting manager of this hatchery. This kiddie-pool-size tub is full of bonytail, so named for their slender, tapered bodies.

“I call these guys my darling little divas because you really got to treat them with kid gloves,” Fry said.

A couple decades ago, bonytail were nearly extinct, the last few scooped up from Lake Mohave in the Colorado River’s lower reaches. Hatcheries like this one have kept them alive while scientists tried to figure out the best way to help them overcome the challenges humans keep throwing at them in the wild.

Bonytail have remained difficult to assess. Their numbers haven’t risen like those of other Colorado River basin endangered fish, and they’re innately less hardy, Fry said. Some research has shown a bonytail can experience a stressful event, like a particularly strenuous move from a retention pond to an indoor hatchery, and hold that stress for up to 45 days until they finally die of it.

“Any time they stress out, one of the first things they do is stop eating,” Fry said. “I like the old adage, a healthy fish is a hungry fish. So if we can keep them hungry, you know they’re healthy.”

The hatchery hit other snags with recovering bonytail this year, too. A team of biologists and technicians would usually spawn the fish in the spring, but this year’s spawning event timed out just as the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning to spread rapidly. They had some bonytail already on site but missed a chance to spawn more because it wasn’t safe to do it at the time, Fry said.

“When you’re spawning the fish, it’s pretty intimate. You’re like shoulder to shoulder, stacked right on top of one another to handle the fish,” he said. “We just figured it would be prudent and wise to not do that.”

Because bonytail are nearly extinct, the science about them has been sparse. Even basic questions remain only partly answered. Do they prefer slow-moving backwaters or rushing canyons? Where do their young stand the best chance of surviving? What diet makes them the healthiest? Answering those questions requires patience, Fry said.

“We haven’t had an ‘aha’ moment or like, ‘Oh, this is what we’ve been doing wrong this whole time,’” Fry said. “We know what we can do for them here in the hatchery setting. The big question is, what do they need out there?”

Tildon Jones, a habitat coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Vernal, Utah, says the goal of the fish program is to restore sustainable populations, not stock the Colorado River. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

‘Hurdles to overcome’

That’s the question for Tildon Jones, Fry’s colleague at the Fish and Wildlife Service. A habitat coordinator for the agency, he looks for ways to help the endangered fish complete their life cycle in the wild, not just rely on people to keep raising them in hatcheries.

On a bluff overlooking the Green River near the Ouray hatchery, Jones points out the features of a riverside wetland. The river – a majority tributary to the Colorado – makes a narrow U-shaped bend, and in the middle is a wetland.

“The river would come up and flood these areas regularly in the past,” Jones said, pointing to the lines of cottonwood trees over a chorus of sandhill cranes that has taken up residence nearby.

This stretch of the Green, with its abundance of low-lying wetlands, used to be a haven for the razorback sucker, known for its bony hump and down-turned, vacuumlike mouth. The fish adapted to the Colorado River’s wild swings between high and low flows by spawning just before the river’s annual spring snowmelt rise. Those flood waters would carry the tiny, just-born fish into protected riverside ponds to grow. At that point, the larval fish look like a grain of rice with two black dots for eyes.

“The timing of those larvae hatching and drifting downriver is such that they would have made it into these wetlands and made it into these habitats,” Jones said.

But the Green River hasn’t acted like its former self in more than 50 years. The Flaming Gorge Dam just upstream holds back those flood waters and regulates the river’s flow, making the tiny razorbacks less likely to end up in wetlands and more vulnerable to nonnative fish that gobble them up.

“The ability of the fish to reproduce and survive in the wild is what really moves the needle from simply stocking fish in the river to having the fish functioning in the ecosystem on their own,” Jones said.

The fish don’t just have one thing working against them, but a confluence of factors keeping them from thriving. If it were just the restricted, regulated flows or just the addition of non-native fish predators, Jones said, the problem might be easier to solve.

Since 2012, the Fish and Wildlife Service along with other partners in the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program have turned their focus to managing wetlands to give razorbacks a better chance of reproducing in the wild and provide juvenile fish the opportunity to grow.

Canals move river water into the wetland during high flows or coordinated releases from Flaming Gorge Reservoir in southern Wyoming, and metal screens keep out the predatory fish. Researchers can then keep an eye on the growing razorbacks before releasing them back into the river.

After seeing some initial success in this approach, and seeing adult razorback populations stabilize due to stocking, Jones’s agency is proposing to move razorbacks from an endangered status to threatened.

“There’s still some hurdles we have to overcome to get them to the point where they don’t need our help as much,” Jones said.

Some environmental groups have said the move is too hasty and have accused the Fish and Wildlife Service of caving to political pressure to show progress in recovering the fish.

Changes to the interpretation of the Endangered Species Act also could affect fish recovery efforts long term. The agency under President Donald Trump recently finalized a rule defining “habitat” as it pertains to endangered species, and while the change won’t likely limit the amount of existing designated habitat for the Colorado River’s fish, it could limit the ability to designate future protected habitat.

But even if the razorback sucker was downlisted from endangered to threatened, Jones said, those working to recover it wouldn’t just walk away.

“The river is highly manipulated. Humans have changed it a lot. And we’re probably going to have to play a role in helping these species survive,” Jones said.

Linda Whitham of the Nature Conservancy stands in front of an expanded channel to deliver water to the Green River wetland’s fish nursery. (Photo by Luke Runyon/KUNC)

Reconnecting the river to its wetlands

After seeing managed wetlands demonstrate successes on the Green River, the Nature Conservancy’s Linda Whitham said it made sense to replicate the idea on a stretch of the Colorado River near Moab, Utah. The environmental group receives funding from the Walton Family Foundation, which also supports KUNC’s Colorado River reporting.

On a warm fall day, big yellow dump trucks moved dirt, excavated as part of a pond expansion at the Matheson Wetlands Preserve. A deepened channel and water control structure with a screen to keep out the predatory fish were also added.

“That was one of our major goals in this project was reconnecting, getting more water into the preserve by widening, deepening this channel,” Whitham said. “And getting the water during high flows into the preserve up the channel into what we’re calling our nursery.”

A combination of invasive salt cedar, or tamarisk, whose roots bind soil along the river, and diminished flows from overuse and climate change have kept the Colorado River locked in its channel.

“Right now, we’re only getting flood events about once every 10 years,” Whitham said. “And that is one of the reasons why the fish are having such a hard time is because the river is not is not able to create those habitats.”

Along with the state of Utah and other partners, Whitham’s group is wrapping up this multiyear, million-dollar infrastructure project, making it a new endangered fish nursery. The next time the Colorado River sees a high spring flow near Moab, there’s a good chance this pond will fill with larval endangered razorback suckers and bonytails, and allow them to grow without being eaten right away.

“As they were in decline, this is one of the last places where wild razorback suckers were collected on the Colorado River,” said Zach Ahrens, a native aquatics biologist with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

If this managed wetland is successful in providing a safe haven, it might be a challenge to find the next spot to locate a similar wetland. Areas to create these kinds of nurseries are limited, Ahrens said, because of how both the Upper Green and Upper Colorado Rivers are bound in tight canyons. But with a few online, they could give the fish the ability to once again complete its full life cycle in the wild.

“Hopefully, you know, with a hypothetical system of these sorts of wetlands, and emulating natural flow regimes, maybe we don’t have to have hatcheries down the line,” Ahrens said.

“A self-sustaining population.”

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced in partnership with public media station KUNC in northern Colorado, with financial support by the Walton Family Foundation.