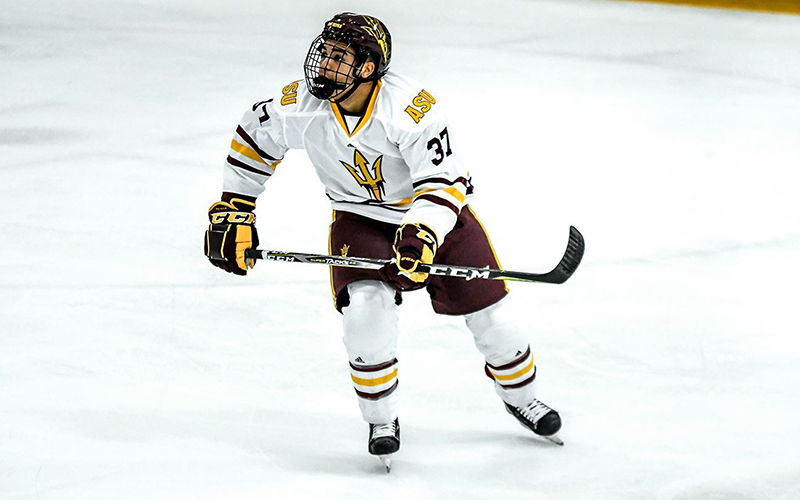

In June, as protests addressing racial injustice swept the country, Dominic Garcia was moved to write an open letter about the racism he has endured in the past. (Photo courtesy of Sun Devil Athletics)

Dominic Garcia fondly remembers playing against the University of Wisconsin’s K’Andre Miller, right, who also is Black. Miller later was drafted by the NHL New York Rangers. (Photo courtesy of Riley Trujillo/Sun Devil Athletics)

PHOENIX – When reality sets in … a deep pain and sadness comes over you. It’s a feeling that lingers no matter what unfolds the rest of the day. It occupies your mind, even though I (along with many others) continue to put on a brave face.

Those are the words Dominic Garcia penned June 17, just weeks after a nation dropped its gloves to react to the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. It was the day the Arizona State University hockey player found his voice and revealed that his journey wasn’t always easy.

The words are especially profound as the Sun Devils prepare to face Minnesota Sunday and Monday at 3M Arena, which is less than 6 miles from the site where Floyd, a Black man, lost his life. As the son of a Mexican-American father and an African American mother, Garcia was made aware at a young age that life would present certain obstacles.

“I definitely did have a discussion with him about racism and the worries of that coming about,” said his father, Frederick Garcia Jr., an officer with the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. “Especially with the hockey, you know, there’s not too many minorities skating around on the ice.”

According to the NCAA’s Demographic Database, 24% of men’s college ice hockey players in 2019 identified as people of color, and just 29 of 4,294 players were Black.

In the NHL, less than 6% of players are Black, Indigenous or people of color.

Garcia, who plays forward for ASU, said he endured his share of discrimination growing up. His first memory of being a target of a racial slur occurred during a game when he was 10.

“It’s not too detailed. I just remember being on the ice and hearing it,” Garcia said. “At the time, I didn’t even know the impact or the weight of the word.”

Then on May 25, Floyd died after Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes, sparking nationwide protests.

The incident inspired Garcia to publish an open letter on ASU’s athletics website, sharing some of the experiences he has had with racism in hockey, and his thoughts on the protests breaking out across the country.

“(The letter) kind of came spontaneously,” he said. “Obviously, right at the time I was thinking about posting, it was during all the protesting and marching in Minneapolis. And (then) you’re seeing stuff in Scottsdale or Phoenix. So I really just tried to listen and watch it and see what happens.”

Once he was assured that Dominic wasn’t expressing anti-police sentiments, his father gave his son his full support.

“I had to make sure that I understood what he was announcing to everyone, what his topics were and how he felt about it,” he said. “I, like many others, don’t appreciate or don’t approve of some of the acts that have been broadcasted or shown on the media from officers, from police officers, rogue officers that have done (bad) stuff.

“But I support his thoughts, his feelings and everything that he felt. I was very proud of how he put it out there and didn’t place blame on anybody, he didn’t make any accusations. … He just was open to conversations with folks, and I was very proud of that.”

ASU coach Greg Powers says learning about the racism forward Dominic Garcia has faced “was sobering, it was sad, and … things that no kid ever deserves to go through.” (Photo courtesy of Pamela Garcia)

Opening up

The letter was a pivotal moment for Garcia, as he had never told anyone before about the things he had gone through, including his teammates and coaches at ASU.

“I honestly didn’t know,” junior forward Jordan Sandhu said. “To hear some of his stories and some of the things that he had to go through, it was pretty heartbreaking. But he’s definitely someone that’s done a great job with it. He’s obviously using his voice for the right reasons, and it touched a lot of people. It touched me.”

“Shame on me, I never asked, but I didn’t know,” ASU coach Greg Powers said. “Because he’s so outgoing, and happy, and always has a smile, and he’s just a huge part of our program. … To read those things that happened to him in his past, it was sobering, it was sad, and certainly (those were) things that no kid ever deserves to go through.”

Even redshirt sophomore forward Peter Zhong, who played junior hockey with Garcia in the North American Hockey League before becoming teammates again at ASU, wasn’t aware of the challenges he had faced.

“I never really personally experienced any discrimination towards Dom or anything like that,” said Zhong, who was born in Beijing and has faced his share of racism in hockey. “I’m not sure if it’s any experience with his past teammates or other opponents, just in general, but that was the first time I’ve heard about it.”

However, Zhong said he can to relate to Garcia’s experiences.

“There were a couple few instances back in the AAA days, where there was that kind of discrimination towards me,” Zhong said. “But (Garcia’s letter) was surprising a little bit. It kind of made me relate to me growing up and what I experienced. It’s really sad, I think.”

Before the addition of the NHL’s Vegas Golden Knights in 2017, hockey wasn’t on many people’s radar in Las Vegas. So when a young Dominic told his parents he wanted to play, they were caught off guard.

“Dominic was playing soccer and baseball before he decided he wanted to venture into hockey, so it was kind of one of those out-of-the-blue things,” said his mother, Pamela Garcia. “I actually told him, ‘We don’t play that.’ I just kind of said, ‘Oh no baby, that’s not our sport,’ because we didn’t know anything about it.”

“I was excited for him,” his father said. “It’s a sport that’s unfamiliar (to) us, other than watching it on TV. The only concern I really had as a parent, initially, was expenses. I know ice hockey was very expensive when I was a kid.”

Garcia’s first foray into the sport was roller hockey. He isn’t sure what drew him to it, but he was hooked from the start.

“I kind of got into hockey randomly,” he recalled. “I tried soccer and baseball when I was young, and then I think we just kind of stumbled upon the rink. I started with roller hockey, so we kind of just walked in there and I think there were people playing, or we must have seen something, and my interest took off from there.”

Although small at the time, the Las Vegas hockey community was supportive and “really tight,” he said.

“Hockey wasn’t very big, so I mean we only had each other to lean on. I think it was three others or four others. We had to leave to play in (California) one year, and our parents would rotate on who would take us each weekend. So Friday after school, we were all meeting up, and we’re out playing for our team in Cali Friday-Saturday-Sunday, and then we’re driving home Sunday and back to school Monday.”

Having a strong community is great for developing young players, but it can only get you so far. His mother knew that for Domenic to continue to improve his game, he would have to leave home.

“There wasn’t a lot for the kids to do, as far as (when) you got better,” she said. “So as the kids got better and better, they had to go outside of Las Vegas. I guess (the Vegas hockey scene) was good for what we knew, for people in Vegas, because we didn’t have a lot to compare it to, so we all thought it was great … but we also knew that our bubble was small.”

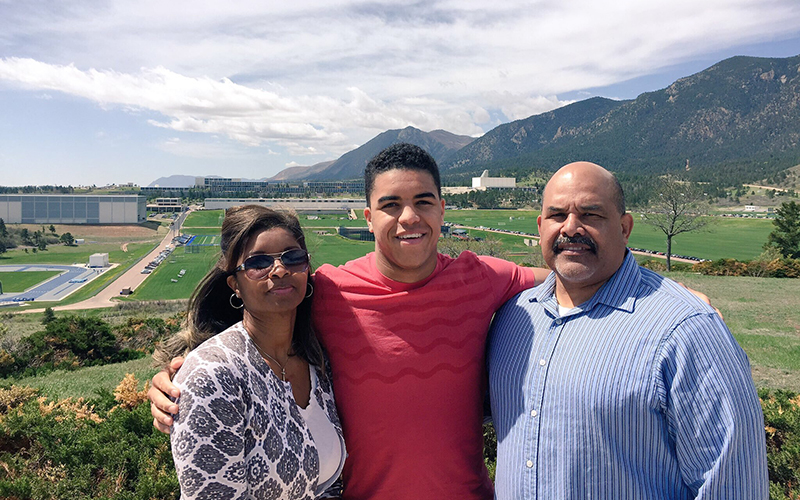

Dominic Garcia says he’s grateful for the support of his mother, Pamela, and father, Frederick. Both are Air Force veterans, and Dominic had committed to playing for the academy before switching to Arizona State. (Photo courtesy of Dominic Garcia)

A new path

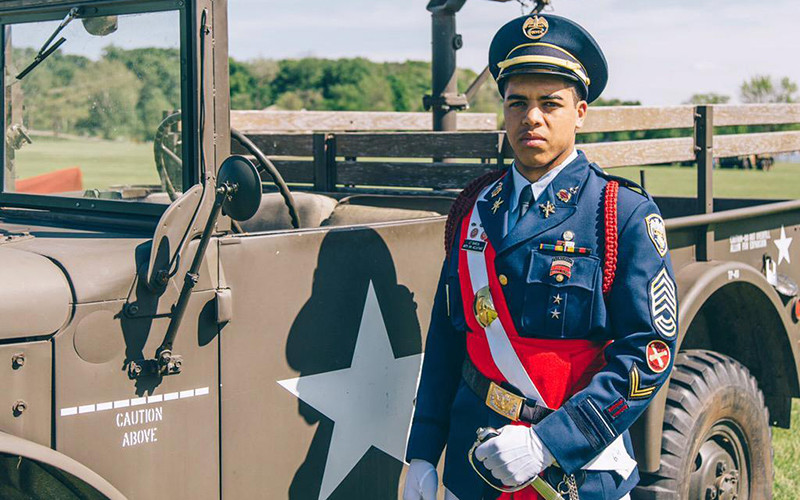

In 2012, Garcia moved to Culver, Indiana, to attend and play hockey for Culver Military Academy. While on a road trip, he recalled, the team stopped for food in an area that was known to be “racially confrontational,” so Garcia remained on the team bus, saying he wasn’t hungry.

“There are tons of different occasions where I may change the way I act, or I change something I do, just so I don’t even have to potentially be put in a situation,” Garcia said. “For me, it was just another thing I’ve gone through.”

When he was in Indiana, his mother said, “we knew the area that he was in … you’ve got these pockets of (Ku Klux) Klan, and … these other pockets of racist little groups out that way, so it’s very weird. When you’re on (Culver’s campus), you don’t really even feel it, because the kids are from all over. But as soon as you leave Culver, it’s very noticeable, so he and I had talked a little bit about that.”

It was important, she said, because “as a Black female, it’s just something that I’ve heard throughout my life. We’ve just always been told that you’re just going to always have to work harder. You’re always going to have to work harder to prove yourself, no matter what.

“It’s not so much that your color is a barrier, per se, but it just means … that you’re going to have to work twice as hard to get what you want. It’s unfortunate, but it is what it is.”

After graduating from Culver in 2015, Garcia moved to Philadelphia to play for the NAHL’s Aston Rebels, now the Jamestown Rebels. There, he met Zhong.

While walking back to the locker room during the first intermission of a game, Garcia was called a racial slur as concession snacks were thrown at him.

“We had just finished the first period. … The kid ran up and yelled it on our way back, and then kind of tried to dip out and take off,” Garcia said. “I think I had my teammates around me thankfully, because I think that was the first time I really snapped during one of those instances.”

Despite the racism that came his way, he was determined to keep chasing his dreams in hockey. In 2017, Powers got his first real look at Garcia’s game in the NAHL Top Prospects Tournament.

“Before we actually ever went to go see him play live, we knew we wanted him,” Powers said. “At that time, we didn’t have anybody that did what he does. The way he plays is such a lost art. He relishes doing all the little things that a lot of guys don’t want to do.”

There was a problem, however.

“Dom was committed to Air Force,” Powers said. “He comes from an unbelievable family, both his parents served in the Air Force. So I think when Dom was young and going through the process of figuring out what he wanted to do and where he wanted to play college hockey, Air Force was a natural fit for him.”

Somewhere along the way, Garcia decided that the Air Force wasn’t for him. After decommitting from the academy in Colorado, ASU quickly became one of his most attractive options.

“It’s always the dream to play at the highest level, but … I always grew up wanting a backup plan,” he said. “I never really wanted to go into business, which seems like what most hockey players go towards. So coming here I was able to do my major, which is forensic psychology, and just be close to home.”

Dominic Garcia moved away from his family in Las Vegas to attend Culver Military Academy in Indiana, where he fine-tuned his hockey skills. He had initially planned to go on to the Air Force Academy in Colorado. (Photo courtesy of Dominic Garcia)

A tough call

Not everyone was excited about his decision.

“(Air Force) really wanted him,” his mother said, “and they were building their team around him, and so for me, that was hard to watch him turn that down because he was going into the unknown at ASU. Even after he decommitted, they called probably for weeks afterwards, trying to get him to come. … For me, it was kind of hurtful that he walked away from that because he was desired in a different way than he was at ASU.”

Despite his mother’s feelings, Garcia committed to ASU and quickly became a favorite among his teammates.

“I think a lot of people appreciate the work ethic that he comes in (with) day in, day out,” Sandhu said. “It’s not an easy job to go out there and block shots and put your body on the line. Off the ice, he’s just a great guy, great leader. … He’s just an overall great person.”

“I kind of see him as a mentor almost,” Zhong said. “He’s always been my captain. Since we played together in juniors he was the captain of the team. Seeing him doing what he does, on and off the ice, just really inspires me, I think motivates me, too.”

Garcia’s coaches are glad they could bring him on board.

“He’s just one of the most likeable kids I’ve ever been around,” Powers said. “Everybody on the team likes him. When you’re in his presence, it doesn’t matter where it is … you feel better about yourself. He has that innate quality in him that he just makes everybody around him feel better about themselves and that’s why he’s going to be so successful in whatever he ends up doing.”

Dominic Garcia poses with the trophy after winning the 2013 North American Roller Hockey Championship with team Reebok/BTM. (Photo courtesy of Pamela Garcia)

Since writing his letter, Garcia has gained not only the respect of his teammates, but even such NHL players as Kyle Okposo.

“Kyle Okposo also reached out. … He reached out and just checked up on me and we talked for probably 35, 45 minutes,” he said. “Growing up that was one of my icons, when he played at University of Minnesota, but it was really cool just to hear from him and have him reach out.”

Garcia’s father is impressed by his son.

“I think it’s very cool to have that support from your fellow players, and then to get it from the NHL players is also very exciting for him, that he’s not alone,” he said. “It made him feel very positive about what he did, as well as my wife and I, we were very proud of the way he wrote the letter.”

One of Garcia’s favorite moments playing for ASU was a small but important one. It came in a game against Wisconsin in February.

“Of all the pictures that have been taken of me on the ice, one in particular has become my favorite,” he wrote in his letter. “It’s the picture of K’Andre Miller and myself playing against one another.”

Miller, a 2018 first-round pick of the New York Rangers, was the victim of a racist incident in April when a Zoom call he was attending with several hundred Rangers fans was hijacked, and racial slurs were repeatedly hurled at Miller throughout the chat.

“You hate to see it happen, but when it does … you almost expect it, always,” Garcia said. “So you feel terrible that he’s the recipient of it this time, but at the same time, I feel like everyone in my situation knows it’s coming again. You can’t avoid it forever.”

Despite the ugliness both men have been subjected to, Garcia sees the photo of them together as a triumph.

“It’s awesome to see, I think anytime you’re out on the ice with someone who you know who’s been through the same type of things. You automatically have a mutual respect for them,” he said. “To see myself there playing against another Black hockey player, I mean it’s awesome.”

And groundbreaking.