PHOENIX – The pay gap is confoundingly stubborn: On average across the United States, women make 81 cents for every dollar a man makes, with the size of the gap varying based on a woman’s job, family status and race.

In Arizona, women fare slightly better than the national data, making 84 cents for every dollar a man is paid. That places the state at No. 11 for the smallest gender wage gap, according to a 2020 study by business.org. When the wage gap is broken down by race, many women are making even less.

Asian women overall are paid the most, matching the Arizona average of 84 cents. The gap grows for Black women, who make 65 cents on the dollar, and Hispanic women, who make 55 cents.

The National Committee on Pay Equity, which advocates for the elimination of the race and gender pay gaps, created a formula to determine how far into the following year different demographics of women would have to work to make the same as a man, on average, at the end of the year. They call each of these days “equal pay day.”

The latest equal pay day was March 31, but a majority of women of color had to wait months longer. For Asian American women, it was Feb. 11, and for Black women it was Aug. 13. It was Oct. 1 for Native American women and will be Nov. 2 for Hispanic women.

“For many years, we had equal pay day on a Tuesday in April,” said Michele Leber, chair of the National Committee on Pay Equity. “We just got to the point last year where equal pay day is in March. Statistically from year to year there is no difference, but it’s inched up a bit this century.”

Experts say barriers are larger for women of color and, although the pay gap may seem entrenched, there are solutions based on policy changes, individual behavior and company systems.

Barriers in female-dominated industries

Occupational segregation is another contributor to the pay gap, but education is becoming less important, said Julia Bear, an expert on the wage gap and salary negotiations.

Industries that are female dominated, such as nursing and teaching, tend to pay less. Even when women enter higher paying industries, such as management or technology, their presence drops the average pay for those fields, according to Jessica Mason, a senior policy analyst at the National Partnership for Women and Families.

The National Women’s Law Center examined common industries where women work:

The highest wage gap between male and female workers was found among janitors, building cleaners, maids and housekeepers. In this field, women made 70 cents for every dollar a man did. On average, women made an hourly wage of $10.10 compared with $14.42 for men in these positions.

The lowest gap was a tie between registered nurses and customer service representatives at 91 cents to a man’s dollar. Women who are registered nurses – a female-centric industry – make an average hourly wage of $30.77 compared with $33.65 for men. For women who are customer service representatives, they make an average of $15.38 compared to $16.83 for men. 89% of registered nurses are women, according to the same study.

Barriers in the job market make it harder for women of color to succeed, according to Kara Stevens, founder of the Frugal Feminista, a website dedicated to giving financial advice to women and families of color.

These barriers include information and networking gaps, along with the fact that advice and discussions on pay aren’t sensitive to race and gender, Stevens said.

The information gap acknowledges the lack of education given to people of color about wealth and wealth creation.

The networking gap refers to the advantage some people have only because they know the right people in an industry.

“I always talk about the analogy of a baseball field,” Stevens said. “Some of us are on second and third base because of the families that we are born into.”

She has experienced a pay disparity during her time in personal finance. She was paid less than white men and women for speaking engagements and brand partnerships.

Barriers for women of color also exist in nonprofits. Women of color are less likely to become involved in the field because most people start off with unpaid internships.

Mason said systemic issues such as this are seen across society, with a lack of representation in government officials and corporate executives.

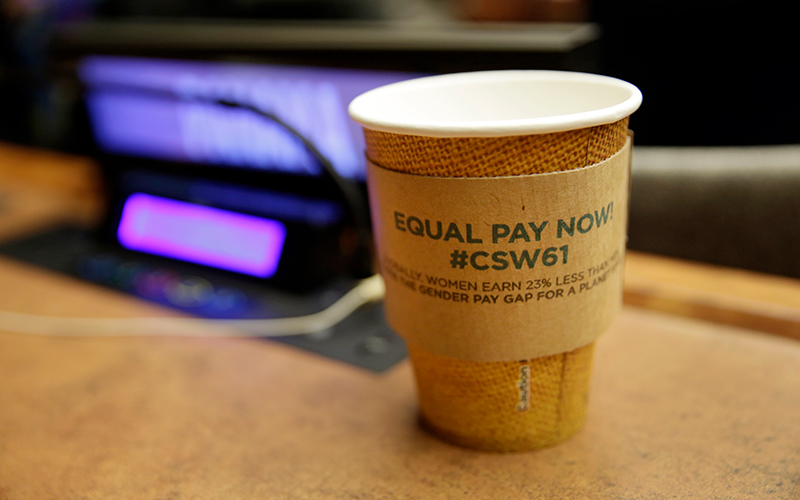

The wage gap is a global issue, with the United Nations taking up the cause. Research predicts the pay gap between men and women, at least in the U.S., won’t close for at least 30 years. (Photo by UN Women/Creative Commons)

Never-ending salary discrimination

Wage discrimination can follow women throughout their careers.

“If someone is discriminated against at one point in their work history,” Mason said, “that sets in stone this discrimination that can follow them from job to job. Employers often use your last salary to set your next salary.”

Certain policies limit how employers can treat a new employee’s salary history and others – such as the salary history ban, which prevents employers from asking applicants about current or past salaries – eliminate that power entirely. In addition, such bans usually stop the employer from seeking that information through the applicant’s previous employers.

As of November 2019, 18 states, six counties and 10 cities had a version of a salary history ban, according to a study done by Sourav Sinha, a graduate student at Yale University. Arizona is not among those states.

States that enforced a salary history ban had a significant increase in the pay of workers who change jobs, an even larger increase in the average pay of women and African Americans who change jobs and no change in rates of worker turnover, according to a study done by the Technology & Policy Research Initiative at Boston University School of Law.

Union membership also has an effect. States with higher rates of union membership usually have a lower pay gap because wages are openly discussed in negotiations with management.

Other contributing factors are women’s reluctance to negotiate for their pay, Bear said, adding that they usually do worse than men when they do so. Mothers are normally the caregivers, which affects how much time they put into a job, and they’re routinely overlooked for promotions.

When employers knew that a woman was the head of household, Bear said, they were more likely to pay her a salary closer to her male counterparts.

Solutions to narrowing the pay gap

Changes in government policy, companies instituting fairness into their salary systems and empowered employees are all key to closing the wage gap, experts say.

The Paycheck Fairness Act, which if passed would add procedural protections to the Equal Pay Act and the Wages and Fair Labor Standards Act, is just one way to end pay discrimination between genders and among races, Mason said.

The labor standards act is a 1938 federal law that established the right to a minimum wage and to overtime pay, and it prohibits the employment of minors in dangerous jobs.

The Equal Pay Act, which amended the labor standards law, requires that men and women receive equal pay for equal work. The jobs do not have to be identical, but very equal. Job content and not job titles determine the equality of work.

The Paycheck Fairness Act bill also addresses wage discrimination regarding sex. It would modify equal pay provisions set out by the Fair Labor Standards Act by strengthening non-retaliation prohibitions, making it illegal for a company to require employees to sign contracts to not share wage information, increasing penalties for violations of equal pay provisions in addition to several other points.

The House passed the bill in March 2019. It has not been passed in the Senate.

“Public policy is one of the biggest drivers, both because of the direct effects it has and in the ways that changing public policy can be an important nudge to change social norms,” Mason said.

The study by Sinha found that states with statewide salary history bans had a reduction in the gender pay gap by about 2 percentage points for hourly and weekly earnings. These changes were primarily caused by an increase in earnings for women, with little to no reduction in earnings for men.

Sinha compared states with statewide salary history bans to states without them, and he studied states that had bans in counties or cities.

His study also found that before the bans, women were 3% more likely to be asked about previous salaries than men. Men and women were both more likely to share their previous pay when asked, but women were 4% more likely to disclose pay history than men.

Based on these findings, Sinha found that women were 2% more likely to disclose their pay history before bans were enacted, even when they weren’t asked. Once the bans were put in place, women had the same likelihood of disclosing their salaries as men.

A few of the societal changes that can help close the gap, Mason said, are discussing salaries with co-workers, strengthening company benefits for caregiving and making caregiving responsibilities gender neutral.

Stevens suggested having a “work husband or wife” to share their salary information with you and advocate for you when it comes to raises. High-level managers also can pressure top company executives to make salary information more transparent so “individuals can use their power together,” Stevens said. “If you do it alone it’s a lot easier for you to be shunned or removed and considered a trouble maker.”

There also is room for pay-gap change at the company level. Two examples are having fair evaluation benchmarks to determine how much an employee could make after a few years with the company, and a human resources department that’s open to employee orientation conversations to fairly discuss wages.

“This is an issue that affects women all their lives,” Leber said.

From the 1960s through the 1990s, Bear said, good progress was made to close this “stubborn gap,” but that has stalled for most of this century.

Research predicts the gap won’t close for at least 30 years. It’s unknown whether the economic shock and human costs of COVID-19 will play a factor in closing it or expand the gap even further.

“Many factors are responsible for the gender and racial wage gaps,” Mason said, “which can make the problem seem a little overwhelming. But, every small change will and has had an effect.”