The death of Dion Johnson in Phoenix led to protests that mirror those across the country over the shootings of Black Americans at the hands of police. In this file photo, protesters gather downtown on May 31. (File photo by Aung N. Soe)

PHOENIX – The state trooper who shot and killed Dion Johnson will not face criminal charges, Maricopa County’s top prosecutor announced Monday, saying the trooper feared for his life.

“Please know these decisions are not made lightly,” County Attorney Allister Adel said at a news conference.

The May 25 death of Johnson, a 28-year-old Black man who had fallen asleep along a freeway in Phoenix, led to protests that mirrored those around the globe over the shootings of Black Americans by police. Authorities have said Johnson struggled when Arizona Department of Public Safety Trooper George Cervantes attempted to detain him.

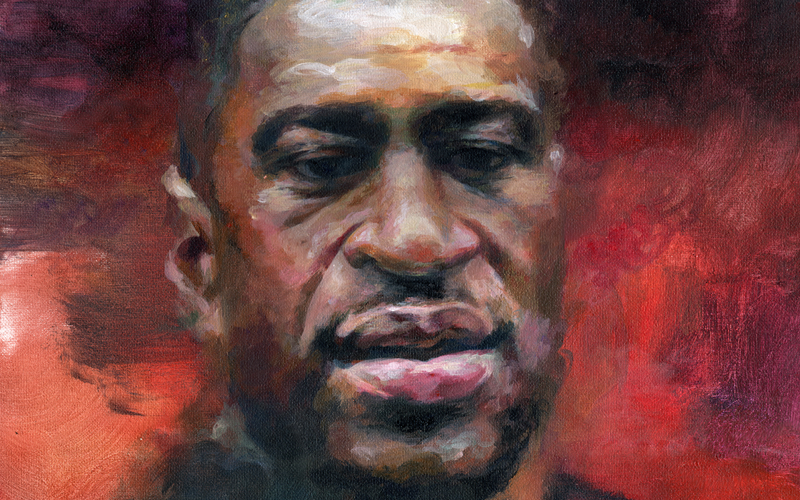

Johnson’s death has not captured the national attention drawn to the deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, but it has driven protests in Arizona.

“Deep in my heart, I knew they were not going to charge him for my son’s murder,” Erma Johnson, Dion Johnson’s mother, said at a news conference after Adel’s announcement.

“I’m still going to fight for justice for my son,” she said, standing with family near Maricopa County Superior Court in downtown Phoenix.

Her attorney, Jocquese Blackwell, said the family will file a notice of claim, a necessary first step before a lawsuit can be filed.

At her news conference earlier, Adel expressed sympathy for the family before outlining the reasons she decided not to charge Cervantes, citing multiple eyewitnesses and “physical and photographic evidence” as corroborating Cervantes’ account of a struggle in which Johnson reached for his service weapon.

In Arizona, people are legally justified to use lethal force if they reasonably believe it is needed to protect their own life, Adel said. To bring charges, she said, it had to be proven that Cervantes did not act in self-defense.

“That cannot be done with the facts of the case,” Adel said.

She noted that neither Cervantes nor backup officers who arrived after the shooting wore body cameras.

She said all law enforcement officers should be equipped with body cameras, despite the financial costs, to make such cases accountable to the public and to aid prosecutors and law-enforcement.

“These are challenges that must be met,” Adel said, pledging to advocate for funding to make body cameras available to all sworn officers in Arizona.

Police-reform advocates have questioned the official account of Johnson’s death, prompting marches in Phoenix and Tempe protesting police and demanding justice and transparency in Johnson’s case.

Despite criticism that police officers often are exonerated for shooting unarmed Black people, Adel said she would charge a law enforcement officer if the officer committed a crime. After she announced her decision Monday, she faced questions about that assertion.

“People of color – year after year, day after day” are being harmed at the hands of police, a questioner asked, but few officers pay for it.

“People of color are losing trust. Besides listening, what are you going to do?” the questioner asked.

Adel replied that she’s committed to transparency: “Someone’s job doesn’t give them a pass.”

The Minneapolis officer who knelt on the George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes before he died has been charged with second-degree murder. Floyd, who was killed on the same day as Johnson, had been arrested and accused of using a counterfeit $20 bill.

One Louisville officer has been fired by no one has been charged in the death of Taylor, a medical worker who died after police entered her apartment using a no-knock warrant, a practice that has since been banned. The city last week reached a $12 million settlement with the family that included several police reforms.

Phoenix police released a 160-page report on Johnson’s death July 15, according to the Arizona Republic, which included Cervantes’ description of the incident and interviews with witnesses, fellow troopers and paramedics.

Adel said Cervantes, a motorcycle officer, found Johnson sleeping in his vehicle, which was parked at the top of an on-ramp on Loop 101, the keys still in the ignition.

The trooper reported that he smelled alcohol and removed a gun from the vehicle and placed it in his motorcycle bag, then called for backup.

As Cervantes waited, he tried to remove the keys from the ignition but could not. He said, according to the Republic, that he walked back to his motorcycle but noticed Johnson was rousing and intended to arrest him to prevent him from driving away.

Adel said a struggle occurred when Cervantes was attempting to arrest Johnson and remove him from the driver’s seat. Cervantes drew his gun and threatened to shoot Johnson if he did not stop resisting, she said. Johnson calmed down and Cervantes reholstered his weapon but the struggle resumed.

Cervantes later said he feared for his life and feared he would lose control of his gun. He shot at Johnson twice. One shot hit Johnson, who died hours later.

Cervantes was questioned on June 1 and he had a lawyer present, the Republic said.

At her news conference, Adel was asked why Cervantes did not speak to investigators for six days. She replied that everyone has the right to not speak to law enforcement officials and prosecutors.

Johnson’s family and supporters questioned Cervantes’ account because it differs from some witness reports.

Some witnesses, according to the Republic, do not describe Cervantes walking back to his motorcycle after initially checking the car. Some described a struggle but do not remember Johnson attacking Cervantes.

Phyllis Tyson, a spokesperson for Black Lives Matter Metro Phoenix who attended the news conference with the Johnson family, said there were many discrepancies in the case and called for change within the Phoenix Police Department, which investigated the fatal shooting.

“This is just another example of the devaluation of a Black human life,” Tyson said.