Ruben Saldaña was 12 when he joined a gang after moving to a part of Homestead, Florida, that he called a ghetto. By 13, he was leading his “junior gang.”

“I became a gang member before I even hit puberty,” said Saldaña, who now runs a mixed martial arts diversion program for kids in high-crime areas in central Florida.

Saldaña said the crimes committed by juvenile gangs had little purpose.

“It wasn’t even like Chicago organizations who were fighting over millions of dollars of drugs,” he said. “It was foolishness. Children who were misguided by misguided kids. The blind leading the blind. And then that’s what I became, a blind leader.”

Dr. Gabriel Cesar, assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice at Florida Atlantic University, grew up in Inkster, Michigan, outside Detroit, where he was always surrounded by a criminal element of drugs, gangs and violence.

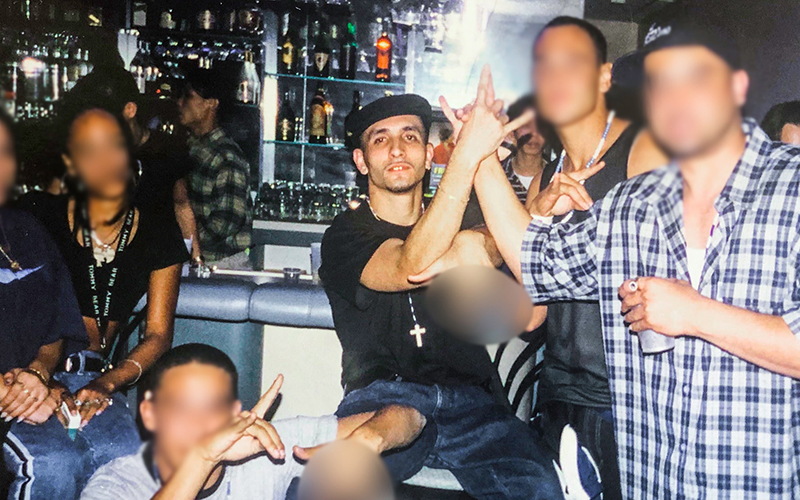

In 1990, at 14, Ruben Saldaña says he became the baby godfather of his gang, where he had 60 to 70 “soldiers” working for him. (Photo courtesy of Ruben Saldaña)

Although he was never officially affiliated with a gang, Cesar would hang around older kids who would sell drugs and commit crimes.

“For all intents and purposes, I grew up in a gang,” he said.

Cesar described gang-affiliated children as “traumatized youth.”

“They are kids that faced adversity in life and didn’t have the social capital and the social network resources to absorb that trauma and overcome it,” Cesar said.

These at-risk children across the United States are exposed to a variety of factors that increase their likelihood of joining a gang, including a lack of supervision, poverty and gang-affiliated families, according to a 2020 article in the journal Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, which Cesar co-authored.

Once children join a gang, experts say, a range of consequences puts them at a heightened risk to enter the juvenile justice system, including an increase in criminal offending and a higher probability of arrest.

“Gang involvement is a risk factor for negative outcomes,” Cesar said. “It makes you more likely to be a victim and it makes you more likely to be an offender.”

Ruben Saldaña, pictured outside his home in Orlando, Florida, joined a gang when he was 12. “There is no safety net for gang bangers,” he says. “When you’re a child – when I was a child at least – there’s never a time for safety.” (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska/News21)

In 2010, there were more than 1 million juvenile gang members, according to self-reported data collected in a 2015 Journal of Adolescent Health report.

In 2012, the National Youth Gang Survey estimated that there were 850,000 criminal gang members; however, this number includes both juvenile and adult gang members, given that law enforcement agencies typically come in contact with older and more criminally involved gang members, according to Dr. James Howell, a senior research associate with the National Gang Center in Tallahassee, Florida.

The lack of recent national data collection on juvenile gangs is because of a lack of federal funding, experts say.

“We don’t currently have a reasonable estimate because the last national gang survey was carried out in 2012,” Howell said in an email.

When gang-affiliated children are imprisoned, they are exposed to lifelong risks, such as “future offending, adult incarceration, substance abuse, financial insecurity and negative behavioral and mental health outcomes in adulthood,” according to the 2020 article in Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice.

In some cases, courts will hand down harsher punishments for the child’s gang involvement.

In Philadelphia and Phoenix, gang-affiliated children were more likely to be imprisoned and held without bail than children who were not associated with a gang, according to the study in the 2020 Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice Journal.

“The juvenile justice system may be imposing additional risks on youth in most need of protection,” according to the same study.

“In its current form, the criminal justice system is ill-equipped to address those underlying root causes,” Cesar said.

Violence breeds violence

Juvenile gangs form in already violent environments that are characterized with marginality and oppression, said Dr. David Pyrooz, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

These environments lead kids to seek some form of safety and protection, which they ultimately find in gangs, he said.

Frank Gottie, current gang member and community activist in Memphis, Tennessee, joined when he was 15 years old. He said he came from a good family but felt he needed “a different kind of love.”

Lucero Herrera now works with the Young Women’s Freedom Center in San Francisco, where she shares her story and advocates for women in struggling communities. (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska/News21)

“I needed that street love,” Gottie said. “They’re going to support you either way it goes. Whether you’re doing positive or you’re doing negative.”

When she was 3, Lucero Herrera moved to San Francisco from El Salvador with her mom and older brother. They lived in Section 8 public housing while her mother worked multiple jobs.

“It was a pretty difficult thing to see my mom working two to three jobs, you know, barely home because she wanted to put a roof over our head,” Herrera recalled.

When her mother was working, Herrera’s brother, who was in a gang, took care of her and cooked their meals. Because of his gang affiliation, Herrera often was stopped and questioned by police.

“The more profiled that I got, I started becoming what they wanted me to become,” said Herrera, who’s now part of the Young Women’s Freedom Center in San Francisco. “If they think I’m this way, I’m going to start showing them that I’m this way.”

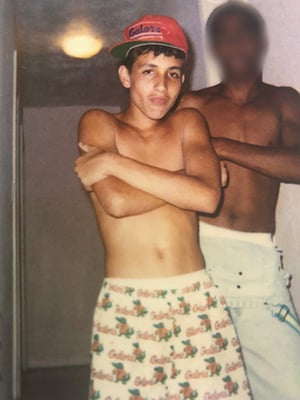

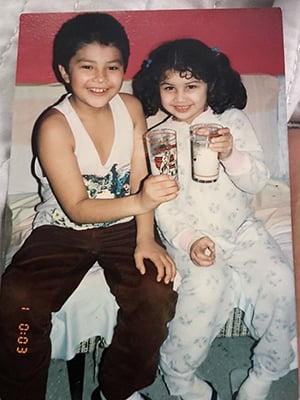

Lucero Herrera was four years younger than her brother, and soon after he joined a gang, she followed in his footsteps. (Photo courtesy of Lucero Herrera)

Children also seek out gangs to make money to survive, according to Eric Davis, executive director of the Base Chicago and former Chicago police officer. Davis saw children who acted as lookouts for gangs and made $25 to $35.

“That doesn’t seem like a lot of money to a lot of people, but that’s a ton of money when you have no money,” Davis said. “The gang feeds them, buys them clothes. That’s real.”

Pyrooz said a mother who works multiple jobs and the absence or incarceration of a father can lead to a lot of “unstructured free time for socializing,” which can lead kids to street socialization and gang affiliation.

KT began running with his neighborhood gang in Las Vegas when he was just 9, following in the footsteps of his father and the majority of his neighbors. “It kind of starts out that way,” KT said.

He also said many of his “little soldiers,” or younger gang members, come from homes where the mother is addicted to crack and the father is incarcerated.

Experts say poor parental supervision and the absence of either or both parents can increase a child’s likelihood of joining a gang.

“There are several adverse childhood experiences that create emotional adjustment problems for kids,” Howell, of the National Gang Center, said in an interview. “Those can be cumulative and increase the likelihood of gang joining very easily.”

Lucero Herrera was four years younger than her brother, and soon after he joined a gang, she followed in his footsteps. (Photo courtesy of Lucero Herrera)

Davis said many youth of color are considered the men of their household, adding, “they make decisions that they have to make, not necessarily that they want to make.”

When he joined the Chicago Police Department, Davis began identifying the dangerous conditions in gang-affiliated neighborhoods. He witnessed families who, by instinct, would jump in the bathtub at the first crack of gunfire.

“You would hear shots and you’d see kids automatically hit the ground like they were soldiers,” Davis said. “As soon as the shots would stop, they would dust themselves off and get back to playing.”

Melvin Farmer, a co-founder of the 83rd Street Crips gang in Los Angeles who now is a gang-intervention advocate, said gang-affiliated children are desperate for mental health services because of what they experience in their neighborhoods.

“I know of areas where kids haven’t trick-or-treated or came out at night for seven years because of gun violence,” Farmer said.

Victims of a system

Pyrooz said entry into the juvenile justice system will only prolong and/or deepen a child’s gang involvement.

“It intensifies their affiliation,” he said. “People prolong their affiliations in gangs in a way that would not have occurred but for their involvement in the system.”

Cesar, of Florida Atlantic University, said gang-affiliated children in juvenile detention don’t develop supportive networks of people who will help them in the future. By being imprisoned, they are pushed “deeper into these criminal subcultures,” he said.

Farmer, who said he was sent to juvenile detention more than 40 times as a minor, called the current system a breeding ground for gang membership.

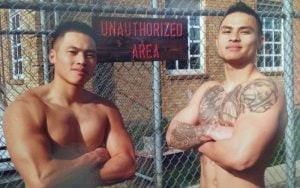

Sang Dao, left, was 17 when he was arrested, and he turned 18 in custody in an adult facility. (Photo courtesy of Sang Dao)

Sang Dao was born into a Vietnamese family in an impoverished area of Oakland, California, where many of his male relatives were gang members.

“It was a rite of passage,” Dao said. “The males in my family – what separated the boys and men was joining a gang and being able to provide for your family and provide for yourself.”

When he was in fifth grade, Dao’s mother moved him and his brother to Portland, Oregon, to escape high rates of gang and gun violence.

But by 13, Dao found refuge among Asian-American gang members on the streets. He struggled with English and quit school, which left him an outsider.

Dao was 17 when he was involved in three shootings in 2007, including a road-rage incident in which he fired into a car carrying a woman and baby.

“It happened so quickly,” Dao said. “I was pretty conditioned to where I wasn’t thinking, and I was just reacting out of fear, adrenaline, anger.”

Dao faced more than 10 years in prison, but after a year in detention, he was given the opportunity to serve half his sentence at Oregon’s Youth Authority’s MacLaren Correctional Facility.

While in custody, Dao earned his high school degree, and in 2014 he graduated magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in criminology and criminal justice from Portland State University.

“It did a lot for me,” he said. “It felt like I was worthy of something or doing something different with my life than ending up in a pine box.”

Just after he was transferred to an adult corrections facility, Oregon granted Dao clemency, with the support of his victims and several local authorities who said they had witnessed his successful rehabilitation.

At 30, Dao now works with youth as a court counselor at Clackamas County Juvenile Department. He works with Oregon kids entering the justice system, including many who have been involved with gangs.

“It’s good work and it’s good for the soul,” he said of his counseling. “But it also hurts your heart a little bit when you see that there’s more people going through what you’ve been through.”

Saldaña, who was running a Florida gang at age 13, started his diversion program in 2014. Ru Camp is a free mixed martial arts program designed specifically for kids in areas of Orlando with high rates of crime and youth violence.

In more than six years of training hundreds of kids, none has been arrested under his tutelage, he said. Ru Camp is a refuge in a jungle of youth violence in which he acts as a paternal figure for the fatherless, Saldaña said.

“Somebody is actually taking out time to spend with them like the parents normally would do,” he said. “They have somebody with lived experiences that can relate with them. We could use any sport, but the thing is, the kids need more than just the training.”

In addition to the benefits of strength and discipline, the sport of mixed martial arts can prevent kids from dangerous criminal activity, Saldaña said.

“I believe that every child in the United States should know how to defend themselves without armed combat,” he said.

Saldaña often works with Farmer, the Crips co-founder, sharing their experiences to steer at-risk youth away from destructive activities and habits that lead to criminal activity.

Saldaña believed he could never leave after he joined his first gang.

“I was told that once you join us, this is for life. I believed in the fantasy. I believed in the myth,” he said.

“The only thing for life is the memories — the good, bad and sad. The last two outweighed the first.”

José-Ignacio Castañeda Perez is an Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation fellow, and Byron Mason II is a Myrta J. Pulliam fellow.

This report is part of Kids Imprisoned, a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country. It is headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.