The Pan-American highway cuts through the center of Panama City. Smugglers use the route to move migrants westward toward the border crossing at Paso Canoas. (Photo by Brendon Derr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

SENAFRONT agents during a training exercise their Meteti base in the Darién province of Panama on March 8, 2020. Despite satellite equipment that can detect activity in real-time, units on the ground still have to make the apprehensions of suspected smugglers and traffickers. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

A SENAFRONT soldier moves through the jungle during a training exercise near the agency’s Meteti base in the Darién province of Panama. Visibility in the Darién jungle can fall well below 100 feet, making the area attractive to smugglers. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

PANAMA CITY, Panama – A spike in migrants moving north through Panama has law enforcement officials worried the country will become an international center for human trafficking.

Last year, nearly 22,000 migrants from Haiti, Cuba and a number of African and Asian countries were detained after crossing the perilous Darién jungle along the Panama-Colombia border, according to Panama’s National Migration Service.

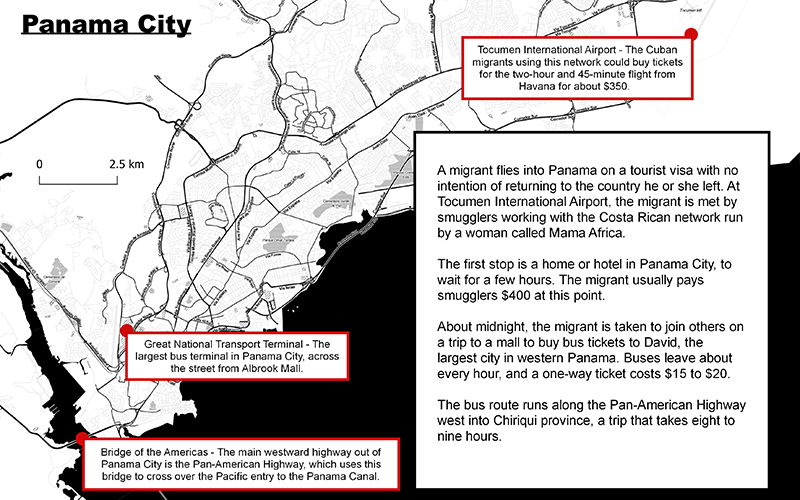

Others choose a much more expensive alternative: paying organized criminal groups to take them through Central America and Mexico and into the U.S. illegally.

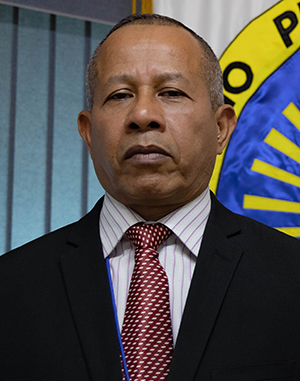

Many of those smuggled by criminal networks legally enter Panama by plane with tourist visas and are picked up by smugglers at Panama City’s international airport, said Emeldo Marquez, Panama’s top organized crime prosecutor.

“Your objective is not to stay here,” he said of migrants. “Your objective is to immediately leave the country to reach the U.S.”

Santiago Paz, director of mission for the International Organization for Migration in Panama, said smugglers are effective at “identifying the routes which are flexible,” allowing them to evade detection from authorities. This also makes it difficult for his organization to measure the problem.

The National Migration Service recorded 6.3 million people traveling in or out of Panama during 2019, with 90% going through the airport. This makes it easy for smugglers to hide their business and nearly impossible to know the true extent of smuggling or trafficking operations, officials said.

Emeldo Marquez is the head prosecutor of organized crime for the Public Ministry. (Photo by Brendon Derr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

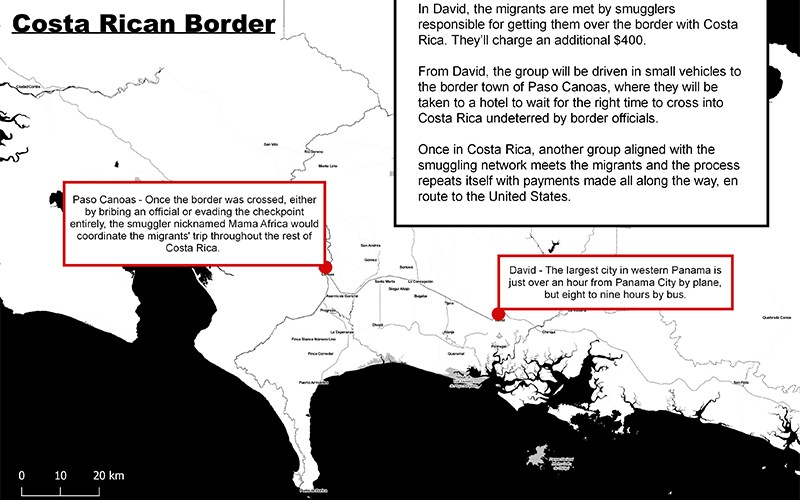

Last year, however, one trafficking group was dismantled. Marquez was part of an international strike force, including law enforcement officials from Costa Rica, with additional support from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and Interpol, that arrested or detained 68 people – 57 in Costa Rica and 11 in Panama.

The smuggling network was led by a Nicaraguan woman who called herself “Mama Africa.” She was arrested in Costa Rica.

“Her job was to receive them and transport them until they reached Mexico,” Marquez said, adding that the organization had a web of conspirators in multiple countries.

“This criminal organization works all through Central American and even Mexico – until people reach the United States,” Marquez said.

The 2019 investigation, called Operation Adalid, started on Dec. 5, 2018, with a tip from Panama’s Ministry of Public Security.

“We had information about people of Cuban nationality who were entering the national territory through the Tocumen International Airport with tourist visas,” Marquez said. “After entering, they were approached by people working in coordination with other groups that operated in the Republic of Costa Rica.”

Mama Africa’s network had been in business for years, officials said.

In 2017, Nicaraguan police detailed a smuggling interdiction operation on the Costa Rica-Nicaragua border that resulted in a shootout with authorities, the death of one smuggler, and the arrest of several others, including Mama Africa’s son, who were charged with migrant smuggling.

The organization was, at the time, focusing on smuggling migrants from Cameroon and bringing them into the U.S. overland starting in Ecuador or Brazil, according to a news release from the Nicaraguan government. But Marquez said that by the time of Operation Adalid, the smugglers had shifted their focus to Cuban migrants.

The journey of a migrant smuggled from Cuba isn’t cheap or easy. Migrants usually learn of the method from friends or family members who made the trip before them, or find instructions posted online, according to Oriel Ortega Benitez, director general of the National Border Service of Panama, known by the Spanish acronym SENAFRONT.

Although there is no guarantee smuggled migrants will make it to the U.S., Marquez said Interpol confirmed to the Panamanian prosecutor’s office that at least 41 Cubans have used the Mama Africa network to make it into the U.S.

In transit, it’s the promise of future payment that keeps migrants safe. If the migrant doesn’t have the money to continue the route, they may be forced to work off that debt though manual labor or sexual acts. Control of a person is what links migrant smuggling to its more heinous cousin: human trafficking.

“It is an abusive situation. They aren’t given food. They are made to work many hours. It is a form of slavery,” said Waleska Hormechea, Panama’s top government official responsible for combating human trafficking.

Her office was established within the Ministry of Public Security in 2019 to train and educate law enforcement agencies on trafficking, as well as help coordinate larger efforts to investigate and prosecute trafficking rings.

Although its clandestine nature makes verification difficult, human trafficking is believed to be the third most lucrative crime in the world – behind only the smuggling of drugs and weapons, Hormechea said.

It is estimated to be a $150 billion a year industry, according to reports from the International Labor Organization.

If their money dries up, Hormechea said, migrants in smuggling networks often find themselves in trafficking situations.

Hormechea recalls a Cuban family who used smugglers to get to Panama, where they had to earn more money to find another smuggler for the next leg of the journey. With no family members to send additional money, she said, they sought out employers who would overlook their lack of documentation, and they were soon taken advantage of and abused.

“It was not the original network that brought them in that trafficked them, but they were in vulnerable condition and that allowed them to be more susceptible to being exploited,” Hormechea said.

She fully expects the numbers of trafficked individuals to rise because the financial incentive is so great. Hormechea also believes more cases will be detected as enforcement increases.

“We are trying to strengthen the prosecution of crime to achieve better coordination between investigators, the prosecutors, and administrative authorities,” she said, adding that the tip that started Operation Adalid came from this sort of intragovernmental coordination.

When tips aren’t available, one of the most effective means of uncovering these networks is by following the money.

In 2018, the first global study on migrant smuggling from the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime looked at 30 smuggling routes around the world and concluded, “there is evidence that, at a minimum, 2.5 million migrants were smuggled for an economic return of US $5.5-7 billion in 2016.” The report noted “this is a minimum figure as it represents only the known portion of this crime.”

Waleska Hormechea is director of the Institutional Office against Human Trafficking, which was created in 2017 as part of the Ministry of Public Security in Panama. (Photo by Brendon Derr/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Often, migrants pay for smuggling through what analysts call “sponsors,” usually family members or friends already in the United States. Funds can be easily sent to cities along the route, through such services as Western Union.

Rich Lebel, director of the Southwest Border Transaction Records Analysis Center in Phoenix, tracks these transfers of money from southern border states to help law enforcement in the U.S. break up human trafficking and migrant smuggling rings.

Money flows are among the most reliable ways to quantify overall smuggling activity, he said, but proving a crime requires tracing each transaction to determine which are innocuous and which are funding organized crime.

“Data is just that, its data,” Lebel said. “How you use it in conjunction with your other investigative resources, then it becomes intelligence.”

Marquez, Panama’s organized crime prosecutor, sees that precision as the greatest challenge for investigations of trafficking and smuggling networks.

“The hardest part about doing this work is that we have to obtain precise information,” he said. “If we don’t have precise information, or if it’s not enough, that’s when we can’t prove that such crime is being committed.”

Although closely related and often conflated, migrant smuggling and human trafficking are distinct crimes.

Migrant smuggling usually involves the illegal transportation of undocumented people who pay to take part in the activity. Traffickers coerce and control their victims, removing their ability to choose.

The strictest interpretation of these definitions would put migrants who engage in smuggling on the same side of the law as the smuggler. However, the U.N. Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime established protocols that ensure the migrants do not also face smuggling or trafficking charges if the smuggler or trafficker is caught.

A SENAFRONT special forces officer gives a briefing at the agency’s Meteti base in the Darién province of Panama on March 8, 2020. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Smuggled migrants “were obviously in a condition of desperation to place themselves in this situation,” Hormechea said, which is why Panama doesn’t prosecute migrants.

Migrants who were smuggled still could be liable for illegally entering a particular country and could face prosecution and deportation, depending on the country in question.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security and Interpol both have a presence in Panama to aid local authorities. The Homeland Security Investigations unit in Panama focuses on identifying organizations that move people across borders.

For large operations against established networks, such as Operation Adalid, HSI agents provide intelligence for Panamanian law enforcement, who then disrupt the crime.

HSI’s main concerns in Panama are U.S. national security – to detect known or suspected terrorists who might use these networks to bypass checkpoints and Panama’s “controlled flow” migration system, according to a DHS official who spoke on condition that he not be identified by name.

Ortega Benitez of SENAFRONT said his agency’s presence at the exit of the Darién jungle has made this route more risky for smugglers who “have increased their prices, because we have more controls.”

He said SENAFRONT focuses on migrant smuggling and human trafficking interdiction because “our border is very attractive for criminal organizations.”

Guerrier Ephese of Haiti gets his photo taken as part of BITMAP biometric screening at the La Peñita camp in the Darién province of Panama. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

SENAFRONT utilizes such tools as the BITMAP program, a collaboration that shares the biometrics of migrants with law enforcement agencies in the U.S. and Europe, to detect criminals and other security threats. Migrants who may be security threats are more likely to engage a smuggler to bypass this system.

Ortega Benitez, who has received extensive training in the U.S., lauds this sort of international cooperation and says it’s essential for moving the needle on migrant smuggling and human trafficking, as well as other transnational crimes.

“We have an infinite number of criminal organizations in the region, and they are more and more organized,” he said. “What does this mean? That we need to work together to counter them.”

SENAFRONT has collaborated directly with Costa Rica, Honduras and the U.S. on operations that have resulted in arrests.

Ortega Benitez describes traffickers as internationally focused.

“Traffickers begin their work in the country of origin and continue all the way to the destination country,” he said.

Smuggling networks like Mama Africa’s also can follow this structure, according to Marquez, but they do not always require large-scale organized networks to move and house migrants.

The profile of a smuggler is very diverse, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime’s global study on migrant smuggling. One reason separate groups of smugglers run different legs of a route is they often are locals who wouldn’t consider themselves a member of any organized crime organization, the study said.

“People who are smugglers in the Darién are mostly natives from the region,” said Marquez, who has also prosecuted smugglers operating in the forbidding jungle. “They are usually farmers and Indigenous people. They transport and guide migrants, and they charge per person and for each stretch separately.”

SENAFRONT Director Oriel Ortega Benitez in his office at the agency’s headquarters near Panama City. Ortega Benitez has had extensive training in the U.S. on hemispheric security. (Photo by Nicole Neri/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

This decentralized structure can make investigations particularly complex and time consuming. Marquez and other Panamanian prosecutors by law are given six months to investigate a possible crime, but he says that’s almost never enough time.

“Depending on the number of people affected, our office can request a complex cause filing in order for the judge to extend the period of investigation – most of the time the six months for an investigation is not enough,” he said. “We almost always ask for an extension.”

One of the most important factors in an investigation is the size and scope of the smuggling network, and for that, Marquez said, international cooperation goes a long way to helping secure a conviction.

“The most important collaboration is information exchange,” Ortega Benitez said. “Organized crime doesn’t have borders, so no country should either – in this sense.”

Cronkite Borderlands Project is a multimedia reporting program in which students cover human rights, immigration and border issues in the U.S. and abroad in both English and Spanish.