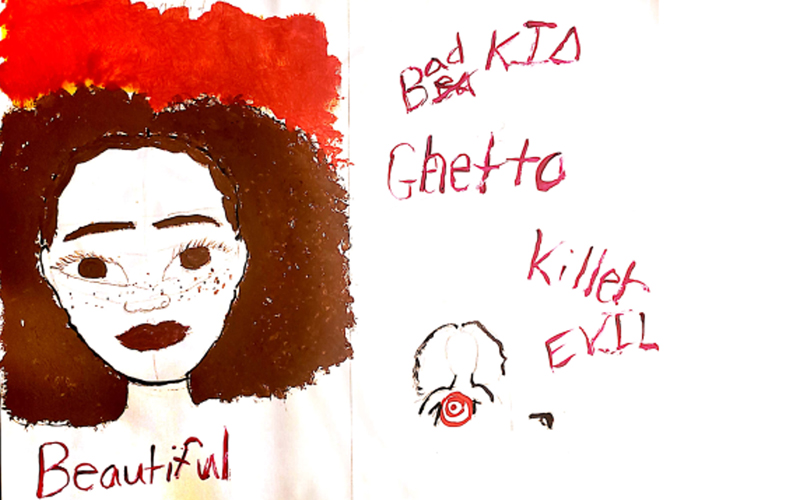

A student’s drawing from Dawn Demp’s project in Flint, Michigan, shows the differences between how students view themselves and how they believe school officials view them. (Photo courtesy of Dawn Demps)

Jayanti Demps-Howell was 9 when he was suspended from school in Flint, Michigan, for a homemade superhero drawing he had brought to school.

He had done the same thing plenty of times before – drawing at home and then bringing it to school. When he was upset about receiving a bad grade, he expressed his feelings through his drawings. In this instance, he drew a cartoon strip of a teacher entering a classroom giving out bad grades and a superhero blowing her up.

Jayanti was suspended for three days for “threatening a teacher.”

His mother, Dawn Demps, an educator who now is earning her Ph.D. in education policy and evaluation at Arizona State University, said Jayanti was expressing himself in a healthy, age-appropriate way, and she was concerned that this “threat” would haunt him in the future.

“It makes it look like he came in there, and he threatened the teacher,” she said. “Like, he never spoke to the teacher.”

Jayanti’s experience isn’t an anomaly. A 2019 study by Princeton University found that Black students are four times more likely to be suspended from school than white students.

The suspension over the cartoon was the beginning of Jayanti’s aversion to school, his mother said.

Demps said her son, who’s 15 now, isn’t much of a talker, and when it comes to serious stuff he expresses himself through art. So when he was 13, she asked him to draw self-portraits of how he views himself and how he thinks his school views him.

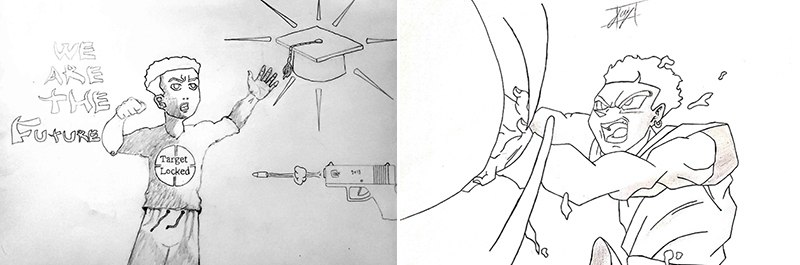

He drew himself as Goku, his favorite character in the Japanese anime series Dragon Ball Z.

“What I was saying is that I perceive myself as being awesome and being cool, to me in my own eyes,” Jayanti Demps-Howell said.

But when he drew himself from the school’s perspective, he drew himself reaching for a graduation cap with a target on his chest. He said the drawing represents how people don’t want Black men to succeed.

“As an educator,” his mother said, “that kind of hurts. But as a researcher, I understand” his feelings toward school.

Jayanti Demps-Howell’s drawings on how his school views him (left) and how he views himself. (Photos courtesy of Dawn Demps)

That led Demps to construct a project asking other students who had been suspended to draw pictures from the same two perspectives. Most kids saw themselves achieving their dreams but thought the school viewed them as failures, said Demps, who’s writing an article discussing the results of her project.

“These kids are very deep. They are not lost on what’s going on,” she said.

As part of her dissertation, Demps is studying the Black Mothers Forum, an Arizona collective working to dismantle what’s known as the “school to prison pipeline” – where school disciplinary actions feed students into the juvenile justice and criminal justice systems. When Demps shared the artwork with the forum, Debora Colbert, the group’s executive director, said it showed how many kids – especially Black kids – feel predestined for prison.

“Imagine being 5 years old and having your hands handcuffed behind you because a teacher said you were a threat,” Colbert said.

A 5-year-old in Arizona did get handcuffed for this reason, she said, and the Black Mothers Forum helped the family stand for their rights. When Demps’ son was suspended a second time from his Arizona high school, the forum helped her family as well.

Colbert said a big focus of the forum is empowering parents to advocate for themselves and their children when it comes to school discipline. Currently, they are helping parents navigate the reopening of schools amid COVID-19.

Demps is working to create a curriculum to educate her son through experiences rather than a classroom. Part of this curriculum is connecting him with successful Black men in the community to highlight a variety of career paths for him to pursue.

The first man he spoke with was Ronald Young, who goes by Chef Ron. After their conversation, Demps-Howell made an Instagram account — @jaycookz_04 — to showcase his cooking, and he began looking into culinary schools. His mother said this was the first time he showed interest in education after high school.

Even if schools reopen, Demps said she isn’t sure she wants him to return.

“I know my son is safe” at home, she said. “I know nobody is targeting him. I know nobody is stereotyping. I know nobody is going to call the police on him for him doing something that teenagers do.”

This story was produced in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Kids Imprisoned” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.