Editor’s Note: Coronavirus has devastated Native American communities and put a spotlight on some long-standing problems in Indian Country that have made this pandemic that much worse. But at the grassroots level, everyday heroes have stepped up to help.

PHOENIX – When the sun is up, he’s up and ready to hit the road by 8. Flatbed trucks are loaded with brimming barrels of water, and the teams take off – up and down the burnt orange washboard roads that crisscross the Navajo Nation Reservation.

Zoel Zohnnie grew up on a ranch in these vast lands, knowing what it’s like to live without running water, knowing what it means to drive for miles to fill up at a community water station and then haul it back home.

“For some families, it’s a whole day of leaving home, waiting in line, coming back, unloading,” he said. “Just to drink water and have water for living.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic arrived on the reservation, Zohnnie saw families and elders sheltering in place – and no one helping them to haul water they desperately needed.

“So I took up a PayPal and purchased a water tank, put it in the back of my truck and hit the road, and ended up doing that day after day,” said Zohnnie, who calls his group Water Warriors United.

Water is a precious commodity that’s scarce in many places across the U.S. but even more so in rural Native American communities like the Navajo Nation, where a virus that requires hand-washing and proper hygiene has taken an especially heavy toll.

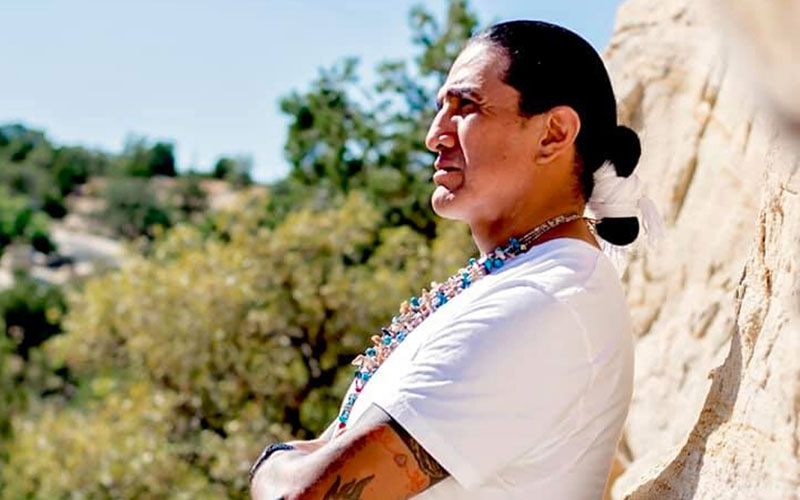

Zohnnie, 42, is a boilermaker by trade, doing pipe welding, power plant maintenance and refinery construction. But he was laid off at the end of March, just as COVID-19 cases began increasing across the sprawling reservation.

He has underlying health conditions that put him at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 and suffering more. But as the virus that causes the disease took hold of Dinétah, he knew he had to find a way to help, even while practicing social distancing and staying safe.

His is the story of how one person saw a problem that needed a solution and started a movement to try to find one – as a friend said, “Changing the world one barrel at a time.”

When COVID-19 started sweeping across the Navajo reservation, Zoel Zohnnie noticed elders and others were unable to access water stations. So he purchased a water tank and started hauling water to them. (Photo courtesy of MJ Harrison)

A scarce resource

A November report released by the nonprofit US Water Alliance found that more than 2 million Americans lack access to running water, indoor plumbing or wastewater services.

Those disparities are worse in communities of color and even more extreme, the study found, among Indigenous people – whose households are 19 times more likely to lack indoor plumbing than those of white families.

On the Navajo reservation, which stretches 27,000 square miles through Arizona and into New Mexico and Utah, an estimated 30% of the 174,000 residents lack access to running water. Many, the US Water Alliance report said, have less than 10 gallons of water in their homes at any given time, sometimes using as little as 2 or 3 gallons a day. The average American uses 88 gallons a day.

Some residents drive hours to get water to haul home, ration what water they do have between hygienic uses and cooking, or stockpile it in case of emergency.

One woman, the report noted, has bartered homemade pies for water.

These obstacles often force residents to travel to towns bordering the reservation to buy water, said Monica Harvey, a Navajo who founded Defend Our Community, a group working to assist elders during the pandemic.

Harvey, who lives in Leupp, points to other problems, such as broken windmills that hinder water pumping and limited hours at tribal chapter houses, the government subdivisions and communal gathering places where Navajos often get their water.

“There was one point … where the chapter house in Leupp was announcing that they were going to shut down a water station,” Harvey said. “The water from that water station is for livestock only. But sometimes, residents have to resort to that water to drink.”

A report by the Navajo Nation’s Department of Water Resources notes that a lack of reliable drinking water “stifles economic growth throughout the reservation” while contributing to higher incidence of disease.

Add an extremely contagious virus into this mix and the circumstances become even more dire, experts note.

“You can imagine if you don’t have access to running water, then the very basic things you need to do to stay home and stay safe during a viral pandemic aren’t possible,” said George McGraw, founder of DigDeep, a nonprofit that works on the reservation to bring running water into homes and schools.

“You can’t wash your hands for 20 seconds several times a day with soap and water. You’re constantly being forced to leave social isolation … to drive to a grocery store that’ll have bottled water … or to drive to a gas station, a truck stop, a school, a library – if they’re open – to take a shower or collect water.”

Cynthia Harris, director of tribal programs at the Environmental Law Institute in Washington D.C., said the long-standing issues around access to water and water quality in Indian Country can be boiled down to three main obstacles: resources, logistics and battles over water rights.

Funding for infrastructure improvements is limited. The Indian Health Service reported last year a backlog of almost 2,000 sanitation-related construction projects in Indian Country and estimated it would cost $2.7 billion to provide all American Indians and Alaska Natives with safe drinking water and adequate sewerage systems.

The rural nature of homes also makes for logistical challenges. On the Navajo reservation, which is bigger than the state of West Virginia, many households are not good candidates for centralized water systems because extending water lines to low-density, mountainous areas is extremely expensive, according to Harris’ group.

“We’ve heard quite a bit from Congress and the executive branch about looking at infrastructure, ensuring that tribes are included in that at a sufficient level,” Harris said, noting some opportunities to address these issues may be part of the $2.2 trillion coronoavirus relief package known as the CARES Act.

“There is a toolbox,” she said. “The question is, which tools bring to bear ensuring tribes are included.”

The Navajo Nation has received $714 million under the CARES Act, and President Jonathan Nez has proposed using $300 million of that for agriculture projects and water infrastructure, including improved residential plumbing.

Final expenditures are being negotiated between the Navajo Nation Council and Nez. But time is running out: The federal government is requiring that CARES Act funding be spent by year’s end.

Navajo elders are among those most in need of clean water, because it can take hours to go out and haul their own. “The idea behind this whole campaign … was to reach the people who can’t get to the water themselves … the people who are … far away enough to have been forgotten,” says Zoel Zohnnie. (Photo courtesy of Water Warriors United)

A hand for the forgotten

“We will never be able to measure the magnitude of language, culture, or history that this virus has taken from our tribes. … We have already lost so much, but are also collectively doing so much.”

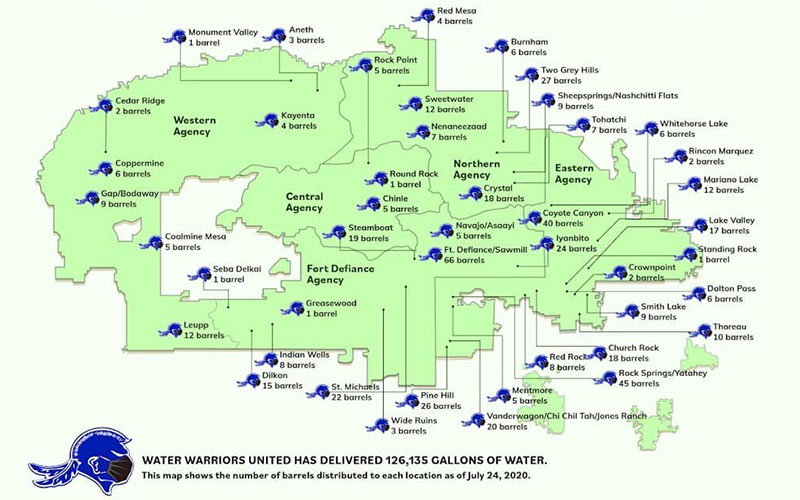

Zoel Zohnnie’s words punctuate the website of Collective Medicine, the nonprofit that serves as the umbrella organization for his Water Warriors United campaign. The effort has grown from one man and one water tank to an operation where volunteers deliver on average 5,000 gallons a week to residents across the reservation.

“The idea behind this whole campaign … was to reach the people who can’t get to the water themselves, and to reach the people who are … far away enough to have been forgotten,” Zohnnie said.

“And there’s been a lot of people that have been forgotten.”

The more he ventured out, the more donations started flowing in. He used the money to buy 55-gallon water barrels for Navajos living out of 5-gallon buckets or small containers.

Zohnnie now has four 16-foot flatbed trucks that carry 550-gallon tanks, hoses, equipment and a water pump. His team has delivered more than 400 barrels and more than 100,000 gallons of water to more than 20 communities.

“Now what we’re trying to do is figure out a refill system for the places we’ve already been, so that we can just go back to these homes and kind of recirculate where we’ve already been,” he said. “But if we do that, then it takes away from us being able to reach other areas that haven’t been given barrels yet.

“So we’re trying to get as many barrels out there as possible, first, so that way at least the residents and our elders and tribal members can have a barrel. That makes their life a little easier when they have to haul water for themselves.”

Along the way, Zohnnie has met dozens of people, many whose circumstances brought tears to his eyes. One family of 18 was living in a small shack with no running water. Another home included several children living alone without water or electricity.

“The dad had passed away probably four months ago, and the mom had passed away two months before that,” he recalled. “So the kids were just trying to make their way, and there was nobody that was really helping them.

“That was one that kind of stuck with me.”

Another man was caring for his 90-year-old mother, who requires a feeding tube. They lived off a 20-mile dirt road and were unable to haul water on their own because the man couldn’t leave his mother for the time it would take to go out and return.

This family hauled water by 5-gallon containers. The Water Warriors gifted them two, 55-gallon drums. The group has delivered more than 400 barrels of water. (Photo courtesy of Water Warriors United)

“It’s been quite an eye-opener,” Zohnnie said. “Growing up on the reservation, you kind of know what’s going on. But until you’re there visiting each home, talking to each person, it never really hits you until you hear them or you look at them in the eye and see how they feel.”

Harvey’s group, Defend Our Community, began collaborating with Zohnnie to get water to the elders it works with.

“It was very difficult for elders throughout the community to get drinking water, so his team came out and was able to provide 55-gallon water barrels with drinking water,” she said. “They had a water tank in the back of their vehicle as well. So elders who needed water jugs or containers filled, they were able to help fill those containers with drinking water.

“A lot of them were so grateful … that a few of the elders broke into tears because they received help. Finally someone showed up to help them, to provide aid to them.”

Zohnnie’s effort is just one of several, and Harris and others note that any permanent solutions to the water access issues must go beyond trucking in gallons here and there. The pandemic, Harris said, is “an opportunity to stop, to pause, to reflect and consider these issues and look at how we can do better.”

Zohnnie hopes to continue his initiative beyond COVID-19, to keep helping his people in whatever way he can. He wants the world to see that not all that’s come from the pandemic is sorrow and tragedy.

“I feel like because of this virus, there are beautiful things happening,” he said. “And I think one of them is the fact that it has brought a lot of people together.

“There’s a lot of people still out there suffering from it, still out there protecting themselves from it, too.”

But, he added: “Even though it’s a dangerous and ugly virus, it has done beautiful things to help people see that we can come together in times of crisis.”