PHOENIX – Named for the biblical figure Joshua by Mormon pioneers who saw its outstretched limbs as a guide to their westward travels, the Joshua tree is an enduring icon of the Southwest.

In tiny Yucca Valley, California, the spiny succulents that once guided pioneers through the Mojave Desert still adorn the landscape, but as climate change threatens their future, residents are increasingly at odds over their preservation.

Some in the town of roughly 20,000 say that by listing the Joshua tree – which actually is a yucca – as threatened, new restrictions will negatively affect the town’s economy, while others view the protections as necessary to ensure the survival of Yucca brevifolia, which is native to the Mojave Desert.

In October, Brendan Cummings, the conservation director of the Center for Biological Diversity, filed a petition to have the western Joshua tree listed as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act.

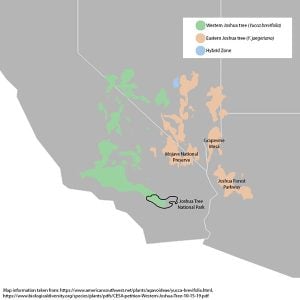

Map showing the distribution of the Joshua tree in the Southwestern United States. (Graphic by Haley Lorenzen/Cronkite News)

The California Fish and Game Commission will vote Aug. 20 whether to make the Joshua tree a candidate for protection, which would trigger a yearlong review before a final vote is taken.

Some of the petition’s recommendations include restricting development on private land on which there is a high density of Joshua trees, and having the California Department of Parks and Recreation develop a management plan to protect the trees in state parks.

“The more we learn and the more closely we study the species, the more bleak their future looks, and unfortunately, that’s the case with so many species threatened by climate change,” Cummings said.

But Yucca Valley residents believe the town’s current protections are enough to protect the trees, and more protections mean more restrictions that would stunt economic development and growth.

“Over the years, we’ve lost a lot of residents due to the fact that we really don’t have a booming economy up in Yucca Valley,” said longtime resident Valerie Valente who believes the petition “limits the possibility of any growth within the community.”

Climate isn’t the only threat facing the Joshua tree

The Joshua tree is native to the Mojave Desert, but a small portion grows within the Great Basin Desert, which continues into Nevada and Utah. Slow growing, Joshua trees are known for their resilience and longevity, with scientists estimating an average lifespan of 150 years.

A study published in June 2019 outlined the possible effects of a warming climate on Joshua trees, specifically in Joshua Tree National Park, which is just south of Yucca Valley.

“The background research found that our Southern California deserts and in effect, almost all deserts in the world, are getting warmer and drier at a rate that exceeds most other places on the planet,” said Cameron Barrows, a research ecologist the University of California, Riverside, and one of the study’s co-authors.

The study found that if the climate continues to warm and become more arid, and no preventative measures are taken, Joshua trees could be almost completely eliminated from the park by the end of this century.

“Are you guys ready to change your name? Because if you look at this paper, you’re not going to have Joshua trees here in the next 50 or 60 years,” Barrows said, recalling a quip he made to park officials while working on the study.

Wildfires in the Southwest also are one of the biggest threats faced by Joshua trees. Although the number of wildfires in California each year has decreased, the size and intensity of the fires has increased, according to research from the World Meteorological Organization.

Cummings said that although adult Joshua trees historically have been quite resilient to fire, the introduction of invasive grasses has resulted in an easier spread of wildfire.

“Now, you start a fire in a Joshua tree woodland, the Joshua tree burns, the grass between the Joshua tree burns, carries the fire to the next tree and beyond and suddenly you have hundreds of acres, sometimes tens of thousands of acres burning,” he said.

Development also prevents challenges for the Joshua tree. Although Yucca Valley has regulations for the removal and relocation of the trees, they still can die in the process.

The Arizona Joshua Tree Forest in Meadview, Arizona looking east toward the Grand Wash Cliffs in 2016. (Photo courtesy of Arizona Friends of the Joshua Tree Forest)

Differing opinions on preservation

For residents of Yucca Valley, the battle has been polarizing.

One of the biggest concerns among those who oppose the Center for Biological Diversity’s petition, including Mayor Jeff Drozd, is the possible negative economic impact on the town.

“Widening roads, it would take more time, more money and more red tape, which really negatively affects our citizens,” he said. “Low income housing will become much more expensive.”

The mayor said he believes the town’s native plant ordinance is ample protection because it requires residents to get an approved native plant permit before the “removal, relocation or trimming of Joshua trees and other native plant species.”

With the new protections, Drozd said, residents would have to get a permit from the state Fish and Game Commission rather than the town.

For example, he said, under current rules, if a Joshua tree falls in someone’s driveway, the resident must go to town hall and receive a permit before it can be removed, to ensure the tree fell naturally.

Drozd was among the five Town Council members who publicly opposed the petition in a May letter to the Center for Biological Diversity.

Valente, who has lived in Yucca Valley since 1969, believes the town’s current regulations are enough to protect the trees, and she blames mostly outsiders for the petition.

“They’re showing up at town hall meetings and wanting to make changes that the town just has been against all along, and now a few people who are obviously loud are trying to make changes within a community that’s been so tight knit all these years,” Valente said.

Gina Grandi disagrees. The lifelong resident of Yucca Valley believes the native plant ordinance doesn’t go far enough because it allows for “so much gray area.”

“They’re more prone to give us another 99-cent store than to give us some kind of leadership on the future of our community and the urgency of climate change,” Grandi said of town leaders.

Burned Joshua tree laying on top of invasive grasses in Joshua Tree National Park in October 2019. (Photo courtesy of Brendan Cummings)

Joshua tree conservation in Arizona

Although the petition would apply only to California, Joshua trees in Arizona are facing similar threats from climate change, which could lead to future protections.

In the northwestern corner of Arizona near Meadview, roughly 40 miles southeast of the Nevada line, lies the Arizona Joshua Tree Forest, which covers more than 44,000 acres. The trees once were thought to be western Joshua trees like those found in California, but they now are categorized as an eastern variant of Yucca brevifolia.

The Friends of Arizona Joshua Tree Forest, a nonprofit in Meadview that aims to document and preserve the forest, has similar concerns regarding threats to Joshua trees.

“If we continue to destroy our world, no matter what that species is, we soon destroy ourselves,” said Sharon Baur, the group’s president.

A Joshua tree bloom opening. Each bloom only lasts about 2 weeks and the blooms typically open in March. (Photo courtesy of Arizona Friends of the Joshua Tree Forest)

In 2016, the nonprofit worked with the U.S. Geological Survey to analyze how climate change affects the trees.

“Joshua trees, as the climate heats up, will be moving north, northerly and higher in elevation,” said Pam Steffen, the nonprofit’s membership director. “So the results of that study were that our forest is middle-aged, with less new growth.”

Similar to groups in California, the nonprofit also worries about the effects of development on the trees, but unlike Yucca Valley, permits aren’t required to remove Joshua trees from private land.

“That happens a lot here,” Steffen said. “People can come in and buy a piece of property and just strip it down to the ground.”

The friends of the forest said that if the petition passes in California, it could make way for more protections for Joshua trees in Arizona.

“It would take some advocacy and certainly it would set a precedent if it was in California that we could possibly move forward on that designation. It would open the door,” Baur said.