PHOENIX — Even before the smoke, Neko Wilson’s anxiety was high.

As a 38-year-old with hypertension and asthma, he had been pushing for weeks to get information about COVID-19. As people around Wilson began contracting the deadly disease, he sought masks and testing, fearing for his health and possibly his life.

Then smoke from the Bush Fire northeast of Mesa rolled into Holbrook in mid-June, worsening Wilson’s respiratory concerns. When he called his brother on June 20, the air quality was poor.

“You could look out the small window and see it was really hazy outside,” Wilson recalled in an interview with Cronkite News. “And we knew the smoke was inside.”

The fire, which has since been contained, prompted the evacuation of hundreds of people, but Wilson couldn’t leave. He’s in lockup at the Navajo County Jail, where COVID-19 was first detected about the time the smoke hit town. Wilson has been held for almost a year on a parole violation for a marijuana conviction nearly 17 years ago.

Now he passes time in increments, one court date at a time. The days until his Aug. 3 release hearing will be spent waiting for phone calls, to learn whether prosecutors will succeed in their appeal to the state Supreme Court to stop it.

“This call will be terminated in 2 minutes,” intones the automated voice of a woman, ending every phone call Wilson makes from jail.

Behind bars and facing COVID-19, every minute counts for him.

The first weekend of July, jail authorities imposed another weekend lockdown, when inmates were held in their cells for longer periods without free time. Like the 62,000 Arizonans behind bars, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, Wilson sits virtually helpless as the pandemic swirls around the state.

With close quarters, shared lavatories and daily traffic of staff members and new detainees, the structure of jails and prisons poses “significant challenges in controlling the spread of highly infectious pathogens” such as the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Neko Wilson has been in and out of custody since 2003. Now, he fights for his release from the Navajo County Jail to escape the risk of COVID-19 behind bars. (Photo courtesy of the Wilson family)

Behind bars, reports of overcrowding and poor sanitation compound these inherent structural challenges of reducing pandemic-related risks for the millions held in local jails, juvenile detention, state prisons, immigration detention and other facilities. Across the country, major outbreaks have been reported in corrections facilities. As of July 8, San Quentin in northern California had more than 900 cases, Butner Low FCI in North Carolina had 640 cases and FCI Elkton in Ohio had 938 cases, to name a few.

In Arizona, 421 COVID-19 cases have been confirmed among prisoners, according to July 8 records from the Marshall Project. As of June 23, there were 496 held in local jails who tested positive for the virus, according to an article by the Associated Press. More than 11,180 prison staff members also have tested positive, it said, and 52 people who regularly entered Arizona detention centers have died.

Lawsuits seeking early release for certain inmates and increased sanitation regulations inside jails and prisons are popping up across the country, including U.S. Supreme Court appeals from inmates in Texas and Ohio, according to several news sources.

Because of the severity of his underlying health issues, Neko Wilson is among those pushing for release to avoid being infected with COVID-19. And as an incarcerated Black man risking COVID-19 exposure, he has several odds stacked against him.

COVID-19 harms Black people disproportionately: Of 123,826 deaths in the U.S. as of July 8, more than 26,700 were Black lives lost, which is more than 1.5 times higher than their population share and 2.5 times higher than the death rate of white people, according to records from the COVID Tracking Project.

These disparities were foreshadowed when U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams warned that, like all people of color, Black people have higher rates for the underlying health conditions – such as high blood pressure, diabetes and asthma – which raise the chances for COVID-19 deaths.

“Black boys are three times as likely to die of asthma as their white counterparts,” Adams, displaying his own inhaler, told reporters during an April 10 briefing at the White House.

“The chronic burden of medical ills is likely to make people of color especially less resilient to the ravages of COVID-19 and is possibly, in fact likely, that the burden of social ills is also contributing.”

In the nation with the highest incarceration rate in the world – four times that of the global average, according to the National Council on Crime and Delinquency – a health threat to the prison population means a threat to 2.3 million people. That includes 451,000 nonviolent drug offenders, 113,000 of whom have yet to be convicted, according to a 2019 study by the Prison Policy Initiative.

Eva Putzova is a 2020 Democratic congressional candidate who’s campaigning on large-scale prison reform and seeks legalization of marijuana use, an end to the cash bail system and an immediate review of nonviolent inmates, including Wilson.

She launched a petition on June 15 demanding Wilson’s release, which has garnered more than 6,900 signatures.

Many of those in jails like the one in Holbrook in the U.S. have not been convicted. More than 462,000 inmates are awaiting trial or sentencing, and they often aren’t released because they can’t afford to post bail, the median of which was $10,000, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. About 448,000 nonviolent offenders were held in jails, according to the 2019 report, but several jails have begun releasing pretrial detainees as a protective measure against COVID-19.

Putzova, who’s running for Arizona’s 1st Congressional District, wants to see the same action in Arizona.

“There are nonviolent offenders who are not presenting threats to society while waiting for their trial,” she said. “They should not be held in close quarters, because clearly, our justice system institutions are not able to prevent community spread” of COVID-19.

Wilson’s defense attorney, Lee Phillips, has sought his release on two fronts: asking the Arizona Court of Appeals to grant bail and arguing in the Arizona Supreme Court that the warrant for Wilson’s arrest in 2009 wasn’t properly filed and resulted in a nine-year delay of due process.

“When I learned about the circumstances of the case,” Putzova said, “I just couldn’t comprehend how he is detained without bail for violation of probation for transportation of marijuana in 2003.”

Crime and punishment

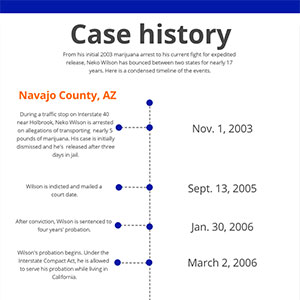

On Nov. 1, 2003, Wilson was stopped along Interstate 40 and found to be carrying just less than 5 pounds of marijuana in his car. He pleaded guilty to transportation of marijuana and was placed on four years’ probation in 2006.

He moved to California, and his probation transferred there. In 2009, he was arrested for his part in planning a botched robbery that resulted in the murder of an elderly couple who illicitly grew and sold marijuana near Kerman in Fresno County. Wilson was not present at the scene of the crime and co-defendants testified that murder was not part of the plan, but he was among six people convicted in the deaths of Gary and Sandra DeBartolo, according to court records.

The felony murder conviction meant Wilson violated the terms of probation for the 2003 marijuana offense in Arizona. According to Wilson’s defense team, under the Interstate Compact Act, Navajo County was required to file a warrant with the National Crime Information Center but failed to do so. If they had, it would have allowed Wilson to serve time for the probation violation concurrently with his California sentence, Phillips said.

Joel Ruechal, the Navajo County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Wilson’s case, said Phillips’ argument fails to recognize the prosecution’s discretion in such matters. Regardless of whether the interstate warrant was filed correctly, Ruechal said, it would have been his decision alone to allow concurrent sentences.

“That is one of our positions we totally disagree on,” the prosecutor said. “The only way to serve concurrent sentences was if I had agreed to it. And I’ve already stated to the court on the record: I would not and did not agree to that.”

So nearly a decade later, in 2018, when Wilson’s felony murder charges were downgraded and he was released from Wasco State Prison in California, Arizona prosecutors were free to pursue charges of violation of probation.

Wilson was among the first prisoners whose sentences were reduced after California overturned its felony murder law. He was among 800 who could receive sentence reductions, advocates said. His conviction was reduced to two counts of robbery, for which he already had served two months beyond the maximum nine-year sentence.

Wilson was released Oct. 18, 2018. His legal team says California officials reached out to Navajo County to inform them of his release. The next day, Arizona opened a probation revocation and later reissued a warrant for Wilson’s arrest. His family posted a $50,000 bond and the warrant was dismissed April 2019, but the same judge three months later granted Ruechal’s request that Wilson continue to be held without bail.

Wilson has been at the Holbrook jail since July 2, 2019. His defense attorney and his brother Jacque Wilson have been fighting since April to bail him out so he can self-isolate at home.

Ruechal, in his argument against bail, cited Arizona rule 7.2 (c), which says a court cannot release a defendant “after a defendant is convicted of an offense for which the defendant will, in all reasonable probability, receive a sentence of imprisonment.”

On June 30, the Arizona Court of Appeals overturned the decision and granted Wilson’s emergency motion to set release conditions, citing the Navajo County Superior Court’s lack of jurisdiction to deny bail. But his lawyers expect delays after a July 1 correspondence from a county judge postponed scheduling Wilson’s release hearing.

As Wilson sits in Holbrook, he also awaits a response from the Arizona Supreme Court, where his due-process case has been pending since January.

Neko Wilson poses with his fiancee, Cassandra, in California. (Photo courtesy of the Wilson family)

Behind bars

According to Wilson, inmates began to suspect an outbreak after jail staff members began wearing masks June 8, months after COVID-19 had taken hold across Arizona and the rest of the country.

Jail staff also instituted lockdowns that lasted 23 to 36 hours. The lockdowns limited inmate movements and reduced free time to a few hours every other day, he said.

Wilson said the jail nurse told him that inmates were showing symptoms of COVID-19 in the cell block next to his, and those inmates had been placed in quarantine for 14 days. Staff told him there were not enough masks for inmates, and they withheld information about the availability of testing or how many inmates and employees were sick, Wilson said.

“A lot of people right now are on the edge, they just want to know what’s going on,” he told Cronkite News in a June 12 jailhouse phone call.

Navajo County officials did not initially respond to requests for information from Cronkite News. However, on June 15, the Sheriff’s Office issued a statement on Facebook confirming positive cases of COVID-19 in the jail. Sheriff’s officials did not provide a number of cases or offer details of testing, but they said “anyone who exhibits symptoms of the virus receives immediate treatment and is further quarantined.”

Nearly a month later, Wilson’s defense team said, his release is all the more urgent because of his asthma. The condition puts him at a “high risk” for dangerous COVID-19 complications, according to the CDC.

When Cronkite News spoke with Wilson again June 17, he had been checked on by jail administration and nurses who took his blood pressure. All inmates were given masks, he said, but he was not permitted to take a COVID-19 test.

Wilson also said jail health officials diagnosed him with hypertension, another condition that heightens his COVID-19 risk, according to the CDC. Independent confirmation is not possible because medical privacy laws prevent the release of individual medical records.

On June 19, jail spokesperson Tori Gorman reported 50 inmates were “placed in different levels of isolation for precautionary measures” and that all new inmates were being screened and quarantined.

Wilson was not among them.

As of June 22, Gorman said, five of the seven inmates tested for the virus were positive, as were nine staff members.

Tests are provided only to those who show symptoms, authorities said, but an inmate must have a high fever and be in “really bad shape” to get one, according to Wilson. He has been asking for a test for months, and his brother has offered to pay for it, but officials refuse, the brothers said.

Inmate safety during COVID-19 has become the subject of lawsuits elsewhere in Arizona, too. The American Civil Liberties Union partnered with the Puente Human Rights Movement on June 16 to sue Maricopa County for inadequate social distancing, hygiene and personal protective equipment available to both detainees and staff.

Jacque Wilson, who is a defense attorney in California, filed a similar lawsuit against Navajo County on July 2, the first anniversary of his brother’s detention in Holbrook. The claim includes allegations that until the June 15 confirmation of the outbreak, the cells and communal cellblock areas shared cleaning equipment and cleaned tables, chairs and phones once per or every other day; that the inmates were not provided masks or regularly checked on until June 17; and that their access to the news and pandemic updates is limited to streaming the final 10 minutes of an evening TV newscast.

On a recorded May 22 video conference with his fiancé, Neko also filmed what he says is sewage water leaking on the floor of his two-person cell, mopped up by a blanket. Meanwhile, an adjacent cell exceeded its occupancy by one, forcing an inmate to sleep on a mattress on the floor.

Jail officials have declined to respond to these specific allegations but said in a June 19 statement that staff and inmates clean and disinfect all contact points within the facility hourly, including housing and common areas.

In his June 15 Facebook statement, Sheriff David Clouse said operating the jail “is an essential function of public safety in all our communities and we will continue to support our local police departments. We greatly appreciate the caring and extraordinary efforts of our jail medical staff along with the close coordination and support from our public health nurses.”

Authorities added that anyone entering the jail is screened through body temperature checks and questions. Staff members have access to protective gear.

Asked about Wilson’s allegations, Gorman told Cronkite News on June 23 that Clouse was “extremely busy dealing with pressing issues,” and Gorman did not respond to further questions.

But the tight-lipped attitude of jail administration gives Jacque Wilson a haunting sense of déjà vu.

A brother’s keeper

Weeks before the Holbrook outbreak, the same scene played out at the Federal Correctional Institution at Terminal Island in Los Angeles, where another of the Wilson brothers, Lance, is serving time. In April, Lance Wilson became one of more than 700 inmates who contracted the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 – about 70% of the incarcerated population of just more than 1,000.

Neko Wilson’s family has been actively campaigning to have him released so he can be isolated at home. His brother, Jacque, right, has been actively involved in the legal battles. (Photo courtesy of the Wilson family)

In an April 29 letter, Lance wrote to prison officials that “the current conditions in this institution amount to punishment and create an unreasonable risk to my safety and health.”

Lance was named in an ACLU lawsuit against Terminal Island that cites overcrowding, lack of social distancing and a threat to medically vulnerable people as a “violation of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution that protects against ‘cruel and unusual punishments.'”

The lawsuit seeks to reduce the Terminal Island population, including the release of Lance and other medically vulnerable inmates, and institute better social distancing, PPE, hygiene and access to care regulations.

Jacque’s fight for Neko’s due process and prompt action after the appellate court decision is energized by fears that Neko could be the second Wilson brother to contract the virus behind bars.

“From day one,” he said, “I had Neko record what was happening inside the jail, only because I knew in Terminal Island I wish we had done that for Lance.”

If released, he said, Neko will isolate with their 85-year-old father in Modesto, California, working in the family car business.

As Jacque continues to push to make that hope a reality, he credits the ongoing legal battles, lobbying, public attention and pressure from public figures for Neko’s case being reconsidered, and for the medical attention Neko received June 17. Jacque and Putzova have been hard at work pushing the #FreeNeko campaign on social media.

“I can’t just sit back and wait for him to die,” Jacque said. “We have to do something.”