MESA – Bringing home a new baby is supposed to be a happy time. Parents spend months preparing the nursery, stocking up on diapers and formula, and waiting excitedly for their tiny addition.

But Christina Loya-Moreno would lie awake at night while her husband and baby slept. For a while, she didn’t think much of it.

“Then it had kind of a spiral effect – the anxiety, the depression, the crying – and that’s when I knew something wasn’t right,” Loya-Moreno said. “But I didn’t know what postpartum depression was at that time.”

Christina Loya-Moreno of Mesa is a peer support specialist at Women’s Health Innovations of Arizona, helping new mothers with their mental health during and after pregnancy. (Photo by Jordan Elder/Cronkite News)

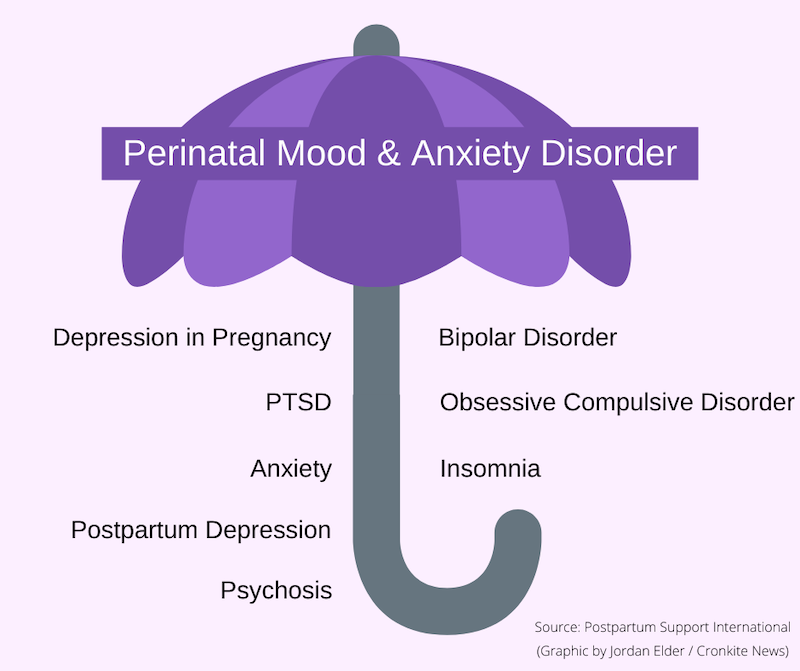

Postpartum depression is one of many conditions that fall under the umbrella of perinatal mood and anxiety disorder. It has long been referred to as the “baby blues,” which are mood swings, anxiety and insomnia up to two weeks after giving birth.

One in seven mothers will struggle with these symptoms more severely and for longer periods of time. That is postpartum depression, and some women are more likely to suffer than others.

A study in the Journal of Racial and Health Disparities found that the risk of postpartum depression is nearly 40% higher in Latina women.

Source: Postpartum Support International (Graphic by Jordan Elder/Cronkite News)

Loya-Moreno, who has three children, now uses her experience to help others, letting them know the condition can be treated and they are not alone. As a peer support specialist at Women’s Health Innovations of Arizona, she works to help new mothers with their mental health during and after pregnancy.

“They know I’m not just sitting here and saying that I understand when I don’t,” she said. “I truly was in their shoes.”

The study said the higher risk of postpartum depression in Latina mothers could be “explained in part by socioeconomic status, community of residence, and immigrant status.”

Loya-Moreno said it’s important to make sure support groups are reaching these women. She offers sessions in English and Spanish.

“Those women are just so appreciative because they oftentimes come from Mexico. They don’t have anybody here,” she said.

“Being from a Hispanic background, the culture is … a lot different as far as reaching out for support and help.”

Loya-Moreno was able to confide in her mother and get the help she needed during each of her pregnancies. Legislators are working to give women without access to such resources the ability to do the same.

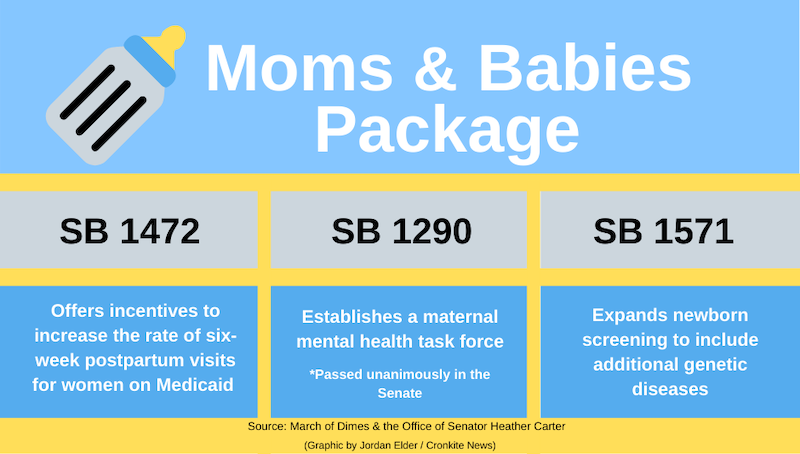

State Sens. Heather Carter, R-Cave Creek, and Kate Brophy McGee, R-Phoenix, introduced a series of bills they call the “moms and babies package” to increase access to care for women in their first weeks postpartum. The bills have all passed in the Senate and are moving through the House.

Source: March of Dimes & the Office of state Sen. Heather Carter (Graphic by Jordan Elder/Cronkite News)

“If we can get those moms into their postnatal visits, then what we are able to do is provide them those services to make sure they’re receiving the health care they need and identify problems that may exist right after birth,” Carter said.

While legislators are working to increase access to care, postpartum specialists are working to decrease the stigma of failing to live up to the “perfect mother” model.

Perinatal therapist Kim Kriesel offers individual counseling, couples counseling and support groups in Gilbert. Social media can amplify negative feelings mothers may have after giving birth, she says. (Photo by Jordan Elder/Cronkite News)

Kim Kriesel at Well Mamas Counseling in Gilbert said social media can amplify negative feelings mothers may have after giving birth. Women have high expectations for themselves, she said, which can push them to the limits trying to follow the message of “women can do everything.”

“They can, but they might not be able to do it in that first year after their child is born,” she said.

These days, Loya-Moreno lives happily with her husband and children in Mesa. She wants women to know that postpartum depression does get better.

“They’re not alone,” she said. “This is 100% treatable with the right care.”

Postpartum Support International has dozens of resources for new and expecting mothers, including an online support group, bilingual helplines and links to local providers.

Support knows no language or barrier, Loya-Moreno said.

“It’s important for all women, any race, any color to have that.”