PHOENIX – A new report from the data firm Civis Analytics says Maricopa County is at risk of the second greatest undercount in the 2020 census – which could end in losses up to $13.2 million in federal funding for some communities that already are underserved.

The report estimates a 70,500 undercount in the county, which represents 1.3% of the 2020 estimated population of 4.5 million. Black, Latinx and undocumented communities in the county are the most likely to be undercounted, the report said. The federally funded programs that are most at stake include Medicare, health insurance for lower income children and education grants.

In addition, the impact of the coronavirus looms over the decennial census, with rural communities, low-income areas and other vulnerable groups more likely to be undercounted as the disease spreads across the United States, according to Latinx state legislators from Arizona, Colorado, Texas and Florida in a video conference discussion on Wednesday.

Fears over coronavirus

The U.S. Census Bureau has delayed field operations until at least April 1, meaning door-to-door census takers will not be able to visit households that have not self-responded yet. There is no specific plan to start field work on the census, which under the Constitution has been conducted every 10 years since 1790.

And it’s not as simple as going online to fill out a census form for some populations.

Texas state Rep. César Blanco, D-El Paso, said his many residents in the Hispanic-majority city already mistrust the government, which suppresses census response levels. Technological challenges add another barrier because more than a quarter of El Paso residents do not have broadband internet subscriptions, which could further limit a community already at risk of an undercount.

Running the numbers

Jonathan Williams, an applied data science manager at Civis, said the firm works with different forms of data, including likely miscount rates and population estimates for 2020, to estimate self-response levels.

“What we’re very interested in,” Williams said, “is who at the end of the entire census process won’t be counted at all? The census has programs and provisions to try to do nonresponse followup, or to even ask a neighbor or statistically estimate where people might be, but none of these methods that they have are as good as self-response.”

The federal government uses the census to determine billions of dollars in government funding for the entire country. It relies heavily on people self-responding, or volunteering, specific details about their lives – such as race and ethnicity, household size and income – that communities of color historically have been reluctant to provide for fear of discrimination or harassment. Some groups’ identities have been ignored in previous census data. But an undercount can lead to a loss of millions in services and programs.

The firm also looks at trends, such as which groups historically have low response rates to census surveys, and then applies them to a modern day context because “the groups of the United States that are least-counted or, most often, undercounted have grown as a share of the population,” Williams said. Such groups include minorities, children and undocumented people.

The county that ranks number one at the risk of an undercount is Miami-Dade, according to the report. Florida state Rep. Javier Fernandez, D-South Florida, on Wednesday attributed that to a large, growing undocumented population in the state, plus crackdowns on sanctuary city measures that discourages his constituents from interacting with the government.

Some Latinx Arizonans are reluctant to respond to the census because of legislation that harmed their community, similar to the situation in Florida, said Arizona state Rep. Raquel Terán, D-Glendale.

The impact of the census goes beyond a population estimate of the nation, states, cities and communities. Census data apportions congressional seats, helps plan for community services and, most important, determines how $675 billion in federal funding is distributed across the nation for schools, infrastructure and other government programs

The reality for many communities, census leaders and advocates say, is that they could have received more government funding if people simply responded to the census.

Grassroots work in Arizona

Getting a complete count for the census can be difficult – not just for census takers, but for activists who have dedicated themselves to work against an undercount. Terán, Blanco and other state legislators said they had to rely on grassroots efforts because they don’t have proper legislative support in their states for a complete count.

See the full map at www.censushardtocountmaps2020.us

Vianey De Anda is census communications organizer for Progress Now Arizona, one of many organizations under the One Arizona coalition with active outreach efforts to minority and underserved communities who will be most affected by an undercount. De Anda has worked since July on educating these groups on the importance of the headcount.

De Anda said One Arizona’s efforts have reached out to various demographics, including Asian-Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, African-Americans, Muslim-Americans, Latinx-Americans, undocumented people and children 5 and younger.

“We’re covering everything from the citizenship question to Title XIII – why it’s important, and even after you vote, or after you respond to the census, your information is completely safe and confidential,” De Anda said.

Although the Trump administration’s proposal to require a citizenship question on the census fell through, De Anda said many undocumented people are still afraid to fill out the census. They fear that essential information, such as their full names and addresses, could be used against them.

“Once we show them the process, and we show them the end result of the statistics report that actually comes out and they see that there’s no names on there,” De Anda said. “It’s just numbers. It’s just data. They realize that it’s not what they thought it was, and then it’s just this really big statistics report.”

Ignoring identities in the census count

Another reason for skepticism is that some communities don’t even see themselves represented on the census form. For example, people from the Middle East and North Africa still do not have their own category on this year’s decennial census, despite decades of pushing for one.

As for black communities in America, data compiled by the Urban Institute found that the black population has been disproportionately undercounted by each census.

And one group in Arizona has worked for years to break that trend.

Arizona Coalition for Change is a grassroots organization with the purpose of empowering and advocating for the Black community in Arizona in issues ranging from civic engagement and fair elections to criminal justice reform.

“We are left out of those conversations continuously and on a regular basis whether with our state, or something as large as the census,” community organizer Danaysha Smith said.

The group approaches a seat at the table differently. When members go out to educate their communities on the importance of government issues – they address and acknowledge the trauma that people of color historically faced when interacting with government entities – A message championed by the coalition’s Tameka Spence, a community activist who died in December.

“I think like it’s always important to emphasize that we were three-fifths of a man at one point,” Smith said. “And so people don’t necessarily feel that there’s a deep connection or value in something as being counted, especially if you felt like you’ve never touched resources that were meant for your community.”

Alexa-Rio Osaki, executive director of civic engagement, said she knows firsthand how the census can create trauma that is intergenerational. Osaki, who is Japanese-American, said 1940 data was used to locate her family members and place them in internment camps.

She said in instances like these, people of color have to confront the things they are afraid of to be able to make their voices heard.

“But please acknowledge those fears because they are real,” Osaki said, “And for those who do not identify as a person of color, please acknowledge what you’re hearing from these unrecognized communities.”

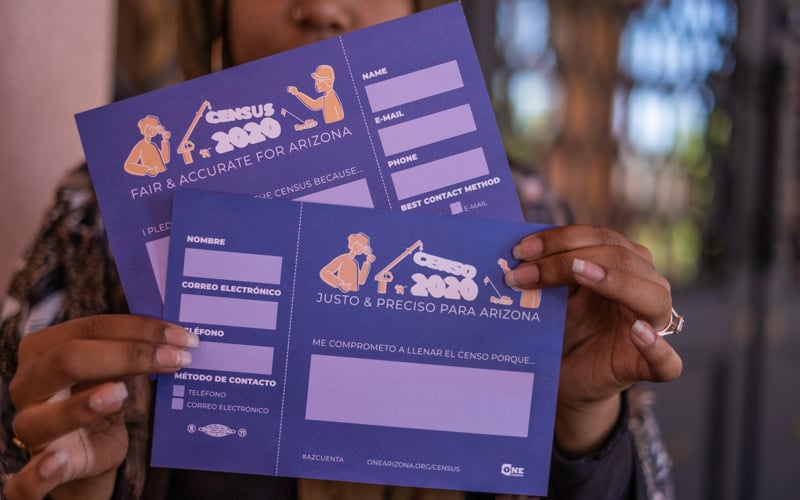

During their educational sessions and workshops, members of the coalition relied heavily on networking within the black community to pledge themselves to responding to the census. Anyone the organization connected with was encouraged to sign pledge cards, which then the coalition reminded them as the census count approached.

For Osaki and Smith, and other activists in the organization, their work first and foremost will always be an “act of love” for Spence. Getting the black community in Arizona to engage in the census is their way of honoring the legacy of someone they say meant the world to them.