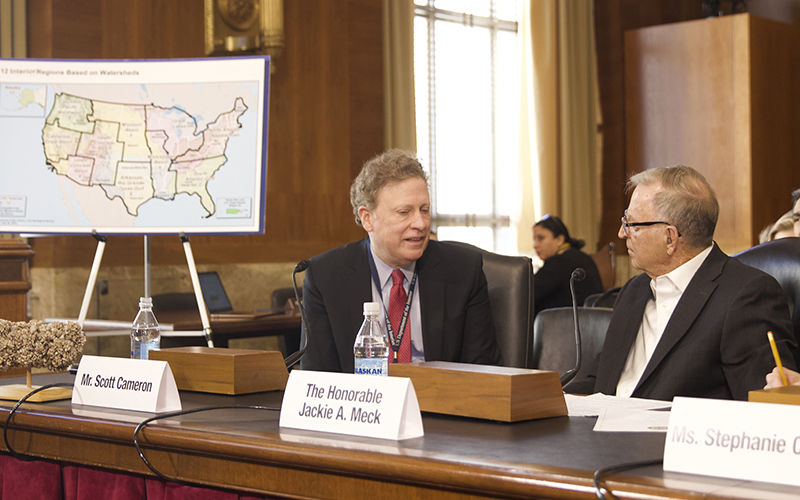

Scott Cameron, principal deputy assistant Interior secretary for policy management and budget, talks with Buckeye Mayor Jackie A. Meck, right, before a Senate hearing on the threat that invasive species pose to water supplies in the West. (Photo by Jessica Myers/Cronkite News)

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nev., left, and Sen. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., at a hearing on invasive species, where a shoe that has been completely covered by nonnative quagga mussels is displayed on the table in front of them. (Photo by Jessica Myers/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Buckeye Mayor Jackie A. Meck said drinking water is scarce enough for cities in the West – they don’t need to be competing with invasive species for it, too.

Meck was one of several witnesses Wednesday at a Senate hearing on the impact of nonnative species – mostly quagga and zebra mussels that clog water intake pipes and force out native species, but also salt cedar that line the region’s riverbanks.

The mussels, native to Europe, were discovered in the Great Lakes in the 1980s and had spread to Lake Mead, Lake Mojave and Lake Havasu by 2007. The fast-breeding freshwater mussels can quickly take over boat hulls, intake pipes, hydroelectric dams – anything under water, as evidenced by the mussel-encrusted shoe displayed on the desk at the hearing.

“It’s been a problem since 2007 and it hasn’t gotten any better,” said Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nev., during the hearing of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources subcommittee. “We need to make this a priority.”

Scott Cameron, principal deputy assistant Interior secretary for policy management and budget, testified that the Bureau of Reclamation’s fiscal 2021 budget request includes $5.6 million to deal with finding and controlling mussels on its facilities.

“The last thing Nevada or Arizona needs are more endangered species because these things are smothering them, or sucking up their food or otherwise occupying their habitat,” Cameron said.

Sen. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., said these invaders can be “devastating” to U.S. waters and that they are “a huge and growing problem in the Southwest.”

But while others were focused on mussels, Meck said the problem for his city are the thirsty salt cedar trees that line the Gila River, sucking up 200-300 gallons of water per day.

Salt cedar trees were first planted in the state in the late 1800s to control erosion and have since spread to 15,000 acres along the Gila River in Buckeye, Goodyear and Avondale. Besides being thirsty, the trees deposit salt around their bases and are highly flammable, which can pose a wildfire threat.

“In Arizona, our desert rivers like the Verde, Salt and Gila have been hit particularly hard,” McSally said in her opening statement. “Right now these riverbeds are choked with up to 4,000 salt cedars per acre.”

The trees are also hard to kill. They quickly grow back from stumps when they are cut down, unless the stumps are treated with chemicals. Federal officials thought they had an answer with a nonnative beetle that can defoliate the trees, but stopped that experiment in 2010 after it became clear that getting rid of the trees would remove nesting areas for the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher.

Buckeye Mayor Jackie A. Meck greets Sen. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., after a Senate subcommittee hearing on invasive species. Meck and McSally both expressed concern about the spread of invasive salt cedars along the Gila River. (Photo by Jessica Myers/Cronkite News)

“The only solution to this problem is to remove the salt cedar,” Meck told the subcommittee, expressing frustration at the bureaucratic red tape that he said is slowing efforts to remove the trees.

George Diaz, the government relations manager for Buckeye, said after the hearing that salt cedars have been removed from 60 acres in the city, which is working to restore native vegetation, like cottonwood and willow trees. But there are challenges, he said.

“Because the area that we’re concerned with lies within a waterway, we have to get specific 404 permits and other kinds of permits,” under the federal Clean Water Act, Diaz said.

The Gila River Restoration Project – a collaboration between Maricopa County, the cities of Buckeye, Avondale and Goodyear and the Maricopa Flood Control District – estimates that removing salt cedars would provide water for 200,000 households, or 600,000 people.

But Robin Silver, a co-founder and board member of the Center for Biological Diversity, said the “holy war against salt cedar” is misguided. He said there is no evidence that removing salt cedars will result in more water for nearby cities.

“It’s not going to give his community any more water – that’s nonsense,” Silver said.

He said that part of the problem is that watersheds in the West have been so changed by human interference that the salt cedar is the only vegetation left in some areas. Silver also challenged the claim that one tree can soak up hundreds of gallons a day, calling that an insignificant amount in the larger picture.

“Even if it were true, you think 300 gallons is going to last very long in Buckeye or Avondale?” he said. “It’s like, that’s probably a shower for the mayor.”

But Meck, who is planning to step down as mayor soon, is not deterred.

The Gila River Restoration Project is working to eradicate salt cedars and restore an 18-mile stretch of the Gila river, the latest in what he called a 25-year effort of “trying to get something done.”