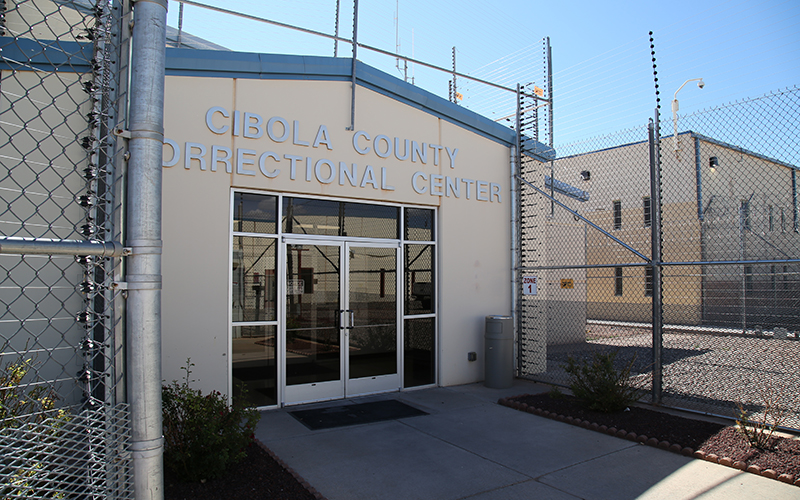

The privately run Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan, New Mexico, has transferred 27 detainees with medical needs to other facilities in the West. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)

PHOENIX – For more than two years, advocates for transgender people have alleged mistreatment of migrant detainees at the Cibola County Correctional Center in New Mexico. Late last month, they say, their efforts partially paid off when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement temporarily closed the facility and transferred 27 transgender women to other detention centers.

“We are happy because this has been a grassroots movement led by transgender women both inside and outside detention,” said Stephanie Figgins of Trans Queer Pueblo, a Phoenix organization that defends the rights of LGBTQ migrants.

However, the advocates say they have more work to do before they reach their ultimate goal: ending the detention of transgender people by ICE.

Trans Queer Pueblo paired with Santa Fe Dreamers Project, a New Mexico organization that provides free legal services to immigrants and refugees, to highlight conditions at the Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan. In a news release, Santa Fe Dreamers Project said “medical neglect, lack of mental health services, poor conditions of detention, and abuse of solitary confinement” have been rampant at the facility since its opening in 2017.

Santa Fe Dreamers Project has advocated ending the detention of all transgender individuals and represented hundreds of women detained in Cibola, said Allegra Love, director and lawyer for the group.

“Our organization’s mission is to get every single transgender person in the United States out of detention and after that, every single person out of detention,” Love said.

Kendra Vides Tesorero, a former detainee and member of Trans Queer Pueblo, said she had mixed feelings about the center’s temporary closure.

“It made me happy and sad at the same time,” Vides Tesorero said in an email sent to Cronkite News. “Finally, justice has been done. But I hope wherever the girls are transferred, that they don’t suffer like they did in Cibola. If I could send them a message, I would say, ‘Don’t give up, one day you will be free.'”

Members of Trans Queer Pueblo march in the 2017 Phoenix Pride parade. The group defends the rights of transgender migrants. (Photo courtesy of Trans Queer Pueblo)

Vides Tesorero was among 29 transgender and nonbinary people who signed a letter directed to civil rights organizations asking authorities for an investigation into allegations of poor medical services and mistreatment at Cibola.

As of Jan. 13, an investigation into the Cibola County center by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties was ongoing, said Katie Hoeppner, the senior communications strategist at the American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico. Since the email exchange between Hoeppner and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, however, the ACLU says it has not gotten any update.

“Every single (transgender) person has been transferred out of Cibola,” Figgins said. “Now 100 percent of transgender women in the nation are in danger, and that’s why we are calling for their immediate release, and an absolute end to the detention of transgender people permanently because ICE is incapable and unwilling to keep them safe.”

In 2015, ICE released an internal memo that provided guidelines on how employees should treat transgender detainees. Love said authorities have failed to follow their own recommendations.

“Since then, two transgender women have died in custody,” Love said.

Roxsana Hernández Rodríguez died in 2018 at Lovelace Medical Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, according to ICE, and Johana Medina Léon died in 2019 at the Del Sol Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, according to USA Today. Both were in ICE custody.

On the death of Hernández, ICE confirmed she was in its custody but reiterated that the proper medical procedure was followed when she first arrived.

“ICE will continue to work with the facility operators to ensure those in our custody at the Cibola County Correctional Center reside in a safe, secure, humane environment with access to necessary health care,” ICE spokeswoman April M. Grant, said in an email to Cronkite News.

A representative from CoreCivic, the private prison corporation that operates the Cibola County Correctional Center, said in an email to Cronkite News that Hernández came to the center gravely ill, and the medical team immediately decided she needed to be transported to an outside hospital.

“Ms. Hernández was only at Cibola for 12 hours, where she stayed in the intake area before being transported to the hospital where she passed away nine days later,” the email said.

In terms of moving the detainees earlier this year, CoreCivic cited medical needs as the reason for the 27 transfers.

“Detainees with unique medical needs were transferred from Cibola County while the facility continues to work through this transition of providers,” Amanda Gilchrist, director of public affairs for CoreCivic, said in an email to Cronkite News.

According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, transgender people are nearly 10 times more likely to be sexually assaulted. Citing a 2012 Justice Department study, it said an estimated 40% of transgender people in state and federal prisons reported a sexual assault.

On Jan. 14, several members of Congress sent a letter calling for the release of transgender detainees if ICE could not provide a safe environment.

“The facility was told, ‘You have 90 days to fix your medical situations. If not, the unit would be shut down,'” Figgins said. “Ninety days passed, and CoreCivic had not improved its medical condition, and that’s one of the immediate reasons that it shut down.”

Like the members of Congress who signed the letter, Figgins claimed ICE has not adhered to its own standards outlined in the 2015 memo.

Even if the transgender unit’s shutdown is not permanent, Love said, the Santa Fe Dreamers Project is committed to ending detention for transgender migrants seeking asylum.

“We are going to continue to work with our clients and continue to work with organizations all over the country with proximity to transgender detainees, and we are going to push our Congress to end transgender detention,” Love said.