TUCSON – A warm breeze blew past Colleen Coyle Mathis and her husband, Christopher, as they lounged on the back porch of their Spanish Colonial Revival-style house one evening last fall, drinking bottles of Pacifico. Marigold, their 2-year-old Bernese mountain dog, lay at their feet, and the music of Linda Ronstadt hummed in the background.

Life in the Mathis house wasn’t always so idyllic. Eight years ago, the couple had boarded up their bedroom windows with plywood and secured their front doors with floor bolts. Colleen, then a health care consultant, met with FBI agents in Washington, D.C., about public threats to her life. Feeling insecure in her own home, she spent evenings with her neighbors and weeks away with her husband in another state.

What made Mathis so fearful? Her volunteer state job. As independent chairwoman of the state’s citizen-led redistricting commission, she became the target of intense organized opposition from tea party-inspired residents and Republican lawmakers to her leadership and the new maps she supported.

Arizona is one of 18 states where independent commissions, instead of state legislators, draw congressional and legislative lines. The panels are designed to keep politics out of the process, under the idealized notion that average citizens would redraw district boundaries after the census without producing stacked, gerrymandered maps.

But during Arizona’s 2011 redistricting cycle, Mathis, a political independent with no interest in interparty squabbles, got caught up in a process so bitter she feared for her own safety.

“We were afraid for our lives,” she said in an understated, steady inflection. Mathis, 53, wears her blonde hair below her shoulders, falling over a sandy blazer and turquoise necklace. “The danger wasn’t far-fetched. It felt like it was at our doorstep.”

With the 2020 Census looming, states are gearing up to redraw the lines again. Mathis’ story shows how high the stakes can be, and how difficult it is to keep deeply divisive politics out of it.

An ‘independent’ process

Gerrymandering, at least for the time being, is here to stay. The U.S. Supreme Court made clear in June that it would not stop state legislatures that draw maps to restrict the political power of minority parties. Chief Justice John Roberts said in his 5-4 decision that while the court doesn’t condone “excessive partisan gerrymandering,” it’s up to Congress and state courts to resolve the issue.

In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan wrote, “Left unchecked, as the court does today, gerrymanders like these may irreparably damage our system of government.”

But there is another way. Instead of having state legislatures redraw maps, states could create citizen-led commissions to diminish partisanship in redistricting.

Anxiety over gerrymandered maps has prompted states such as Arkansas, Nevada, Oklahoma and Oregon to consider establishing panels through 2020 ballot initiatives.

“If we don’t fix this now, then we’re screwed for a decade,” said Andy Moore, founder of Let’s Fix This, an Oklahoma-based civic engagement nonprofit supporting the Sooner State effort.

For states looking to adopt independent redistricting commissions, Arizona is a model to study, said Justin Levitt, associate dean for research at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, and a former Justice Department senior voting rights official in the Obama administration.

In the past two years, voters in five states — Colorado, Ohio, Michigan, Missouri and Utah — and legislators in New Hampshire and Virginia voted to create independent redistricting commissions or other limitations on the state legislature’s ability to redraw district lines.

“It shows that Arizona was on the leading edge of a modern trend,” Levitt said. “This is not a blue-state or red-state thing.”

Often, there is pushback.

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu, a Republican, vetoed his state’s bill in August. Meanwhile, Michigan Republicans are suing the state in federal court over the constitutionality of its system. That hasn’t stopped Michiganders from pouring in applications to join the 13-member commission: In the first week, 3,000 people applied.

During the 2010 redistricting cycle, Arizona’s new commission faced strong opposition from Republican leaders, then dominant in the state, who waged a six-year battle that ended only when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the commission.

Mathis, the commission’s independent chairwoman, was at the center of the fight.

The fight started immediately

Mathis’ involvement began in 2010, when she came across a pamphlet for the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. The state was seeking candidates to fill the five-person panel tasked with redrawing district boundaries. After surviving a breast cancer scare several years before, Mathis, who was working full time at the University of Arizona Health Network, was looking for ways to give back.

Her husband encouraged her to apply to become the independent chairwoman, serving with two Democrats and two Republicans. But, the attorney warned her, “You should know you could get selected.” To her surprise, she did.

Friction was almost immediate.

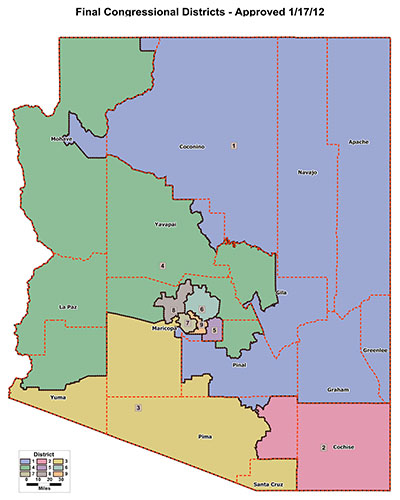

The final congresssional district map after the 2010 Census when Arizona gained a seat, its ninth, in the House. The state is expected to gain another seat after the 2020 Census. (Map courtesy the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission)

At a public meeting of the panel at Pima Community College on a scorching hot June afternoon in 2011, one person after another berated Mathis. They were angry about what they thought were Democratic-leaning decisions, including hiring a mapping consultant with ties to President Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign.

A Marana resident stood up and lambasted the panel from the microphone, according to transcripts: “I thought this commission was supposed to be nonpartisan. Dammit you can’t get any more partisan than this, and I hope you got that. I am so mad over this.”

Weary after three uninterrupted hours, Mathis spilled water on her skirt. When the commission recessed, she cried in the back room. How could people be so angry, even before there were any maps to be angry about?

The two Republican commissioners ended up clashing with Mathis and the two Democrats over who should serve as legal counsel, which firm to hire as the mapping consultant and, eventually, the congressional and legislative lines.

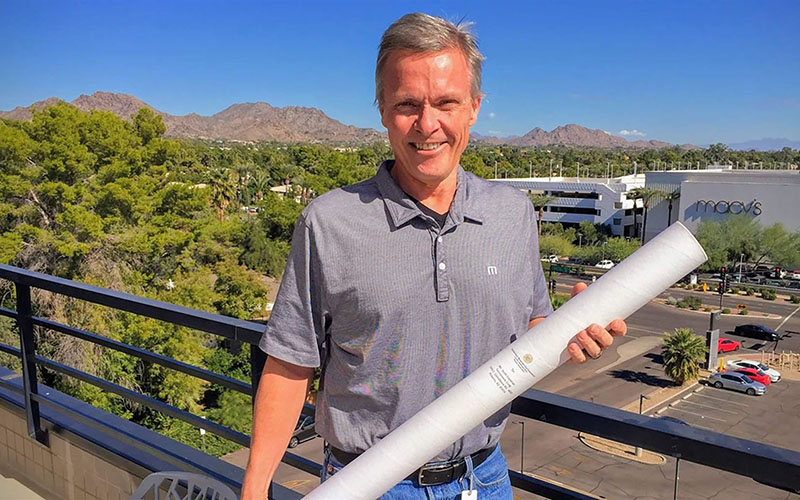

Scott Day Freeman, a commercial litigation attorney and a Republican member of the commission, said he noticed troubling aspects about the commission and Mathis’ leadership style from the beginning. Irked by what he thought was her early indecision and hidden sympathy for the Democratic Party, he said he knew the maps would skew Democratic.

“At that point, there wasn’t much more to do but to vote ‘no,'” Freeman said during an interview last fall in his Phoenix office. He wore light blue jeans and a gray golf shirt that matched his hair, and leaned back in his chair as he spoke. “These maps weren’t drawn in the public. It was constitutionally suspect.”

Adding to those concerns was Mathis’ husband. Christopher worked on a moderate Democrat’s campaign for the state legislature, focusing on Republican outreach and fundraising. A lifelong Republican, he cut his teeth in politics working for Republicans such as former U.S. House Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois and former U.S. Sen. Chuck Hagel of Nebraska.

The married couple always assumed their friendships with members of the conservative Federalist Society would be the bigger controversy. They were clearly wrong. The floodgates opened to Republican attacks, saying Mathis was biased toward Democrats and needed to be removed.

She found it insulting and sexist that critics couldn’t separate her husband’s work from hers. She made decisions based on what she felt was right, she said, and what was required of her by law, including provisions that emphasized competitive districts that put the commission at odds with Republicans in power.

Republican state Sen. Frank Antenori, using what he later said were “military analogies” that were not intended as violent threats, said in mid-July 2011, “The gun is loaded and it’s just figuring out what target to point it at and when to pull the trigger.” His comments came just seven months after then-Rep. Gabrielle Giffords had survived a gunshot to the head at a district event in Tucson that killed six and wounded 13. The memory of the assassination attempt on Giffords was fresh in Mathis’ mind.

Phoenix attorney Scott Day Freeman, holding Arizona’s legislative maps, was one of two Republicans on the state’s independent redistricting commission. He often voted against Mathis and the two Democratic commissioners on key decisions. (Photo by Stateline/The Pew Charitable Trusts)

On the same July 2011 day that Mathis met with FBI officials about threats to her life, Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne, a Republican, announced an investigation into Mathis and the rest of the commission to see if they had violated any laws. He was setting the stage for her removal.

In decision after decision, from choosing the commission’s legal counsel to choosing its mapping consultant, Mathis proved she was “a very highly partisan Democrat,” Horne told Stateline recently. The result was a map far more gerrymandered than any the Republican legislature could have drawn, he said.

“She and the two Democrats colluded in secret to do a number of things that I thought were highly improper,” he said. “And they got away with it.”

By fall of 2011, Republican Gov. Jan Brewer was ready to remove Mathis with the support of the GOP- dominated state Senate. Mathis’ lawyers asked her if she wanted to fight. “Of course,” she said, “I’m Irish.”

Saving her job and the commission

Two weeks after Mathis was ousted, former Arizona Chief Justice Thomas Zlaket represented her before the state Supreme Court. A portrait of Zlaket hung on the wall of the hearing room.

Lean and mustached and wearing a charcoal suit, the former chief justice argued in a gravelly voice that if Mathis wasn’t reinstated, the commission “becomes a joke, a laughable joke subject to manipulation by the very people that the commission was designed to insulate from.”

The court was unanimous in reinstating her.

It was far from the last legal challenge. Republicans would litigate several aspects of the process in the coming years, such as its constitutionality and the standards by which maps were drawn. But in each case, the commission and its maps prevailed.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Arizona’s redistricting process in 2015 and its legislative maps in 2016. A Maricopa County judge upheld the congressional map the following year.

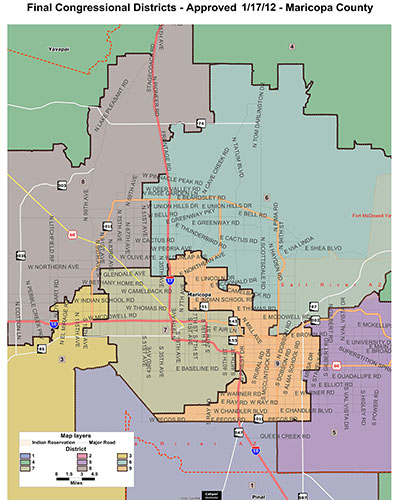

A detail of the state’s congressional district map shows the boundaries of the districts clustered in and around the Valley. (Map courtesy the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission)

“She was the focus of a lot of controversy, but not in a sense that was warranted,” said Levitt of the Loyola Law School. “She was the chair of the commission that the prevailing party didn’t appreciate. The commission put their heads down and did the job citizens told them to do.”

But it took a personal toll on Mathis. Shortly after her reinstatement in 2011, back in her childhood home in Peoria, Illinois, for Thanksgiving, she faced doubts from family members about her judgment. Conservative Republicans, they had followed the saga in Arizona and wondered if she should quit. “It was tough,” she recalled, looking down and rubbing her forehead.

Throughout these legal battles, Mathis was “an unsung hero,” said Paul Charlton, a former U.S. attorney for Arizona who also represented her in the process. A “McCain Republican,” he thought the attacks by fellow members of the GOP were troubling.

“I don’t know if anyone knows how much courage you have until you’re tested,” he said. “This is a woman who showed extraordinary courage in the face of some grossly unfair personal attacks. Character matters in everything and most certainly in this instance.”

To this day, a mug with Charlton’s face on it sits on the kitchen counter in the Mathis home.

Freeman, the Republican commissioner, can’t bring himself to hang the final maps on his office wall. Instead, they sit rolled up in the corner.

While he resisted pressure from friends to walk away from the panel, he remains disappointed with the process. Proponents, he said, argue the system takes politics out of redistricting. On the contrary, he said, the system was “hyperpartisan.”

“It was a great privilege,” he said. “Would I do it again? I think I would. But it was hard. It certainly didn’t play out the way I thought it would. It veered almost from day one.”

At a Mexican restaurant down the foothills near their home, the Mathises in November bantered about the saga over chile rellenos.

They have known each other since high school back in central Illinois. Christopher went to every commission meeting to support Colleen during the trying time. He earned the pejorative title of “sixth commissioner” from Freeman and others.

The commission, she said, was not a team, and she regrets that. They didn’t get to know one another personally, and the result was that they couldn’t agree on anything. The process is inherently political, she said. “You just can’t take politics out of it.”

Broadly, though, she accomplished her goal: She oversaw the mapping of “fair and competitive” districts, she said, and obtained Voting Rights Act approval from the Justice Department on the first try.

Before the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, Arizona was one of nine states that needed federal approval for any measure that might restrict ballot access.

Since the legal battles ended in 2017, Mathis has become an evangelist for independent redistricting commissions, speaking in different states and universities and serving a three-year stint in the political science department at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, working on voting technology and data.

In September, she co-authored a paper for Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, outlining Arizona’s system as an alternative to gerrymandering and offering practical lessons for other states, such as insulating the commission from outside influence and interference. She hopes other states will adopt a system like Arizona’s. And she doesn’t regret serving on her state’s panel – despite how difficult it was.

“I went into this with no agenda or preconceived notions of any outcomes or decisions along the way,” she said. “I was a clean slate. I just wanted to be in public service, and this was the way to do it.”

– Stateline is an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.