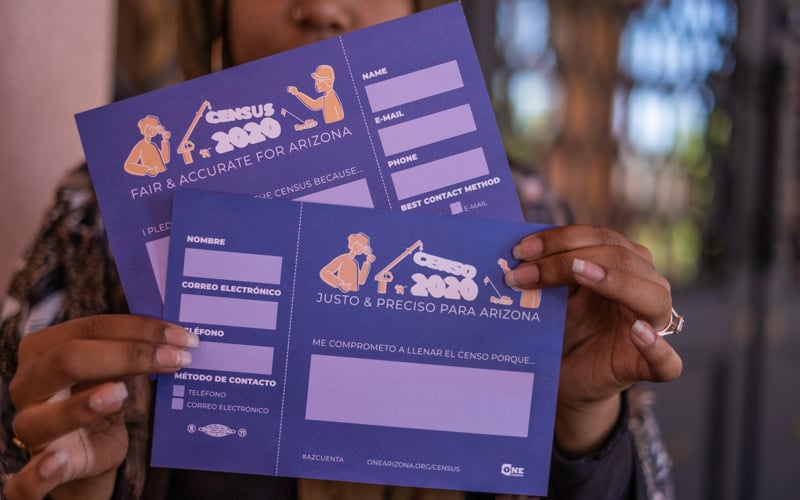

National and local organizations, including the Phoenix Indian Center, are working to ensure a more accurate count for Native Americans in the 2020 census. (Photo by Deagan Urbatsch/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Time, distance and technology limitations are among the reasons Native Americans may be the most difficult demographic to count in the 2020 census, the Census Bureau says.

But lack of trust is the biggest reason, said Patty Hibbeler, chief executive of the Phoenix Indian Center, which provides workforce and youth development, drug and alcohol prevention and language and culture revitalization.

“It comes from a very long and very negative history with the federal government,” she said.

In the 2010 census, 4.9% of American Indians living on reservations and Alaska Natives went uncounted – the highest of any group, according to an official Census Bureau audit. One in 7 Natives was left out of the equation the federal government uses to distribute more than $600 billion based on census data.

Native Americans, along with Latinos and African Americans, have been undercounted since the first census in 1790.

To halt this historical financial, political and societal disparity, an Arizona census outreach organization and leaders of local and national Native groups are mobilizing.

Hibbeler wants to avoid a potential undercount in the 2020 census, which officially launches in January, so more federal funds will go to schools, roads, hospitals and other needs of Native Americans in Arizona. The census, which is required by the Constitution every 10 years, also determines which states gain or lose seats in Congress.

“Our first goal here at the more urban Indian Center is to build trust within the census and inform the population how that data will be used,” she said.

Census officials are battling barriers to the headcount, such as using tribal input to ensure extended family is counted, hiring census workers from Native communities, and gathering information on geography, recruitment activities, data collection, outreach and promotion, according to a 2018 statement from the Census Bureau. It says that since 2015, bureau officials have met with more than 400 tribal delegates representing 250 different tribes and organizations across the country.

“The Census is a critical and powerful information source that will significantly influence American policy for the coming decade,” the Congress of American Indians says on its website. “It is the foundation of American democracy in that it determines the allocation of Congressional seats. It is also used extensively to distribute funds to tribal, state, and local governments, and it serves as a foundation for policymaking as well as research and program evaluation in think tanks, universities, and at all levels of government.

Trust, geography and internet access

Kristine Firethunder, director of tribal relations for Gov. Doug Ducey, is tribal outreach liaison for Arizona’s census efforts. She acknowledged Native Americans’ mistrust of the federal government.

“Yes, trust is a tremendous concern,” Firethunder said. “In this particular case, we are working with our partners to recruit American Indians residing in traditionally hard to count areas to perform two tasks: enumerate and speak traditional Native dialects. For obvious reasons, it is easier to trust someone already living in your area and who speaks your language.”

Asa Washines, senior policy adviser at the Navajo Nation Council’s speaker’s office, knows firsthand about difficulties in collecting data.

“In my experience from the Pacific Northwest,” Washines said, ” I’ve seen a long history of distrust from people. They can be scared of the data collection, but they seem to open up more once we explain why it’s important to participate.”

Effectiveness of outreach questioned

Some critics say the Census Bureau’s efforts on the 2020 census are ineffective. On is a marketing campaign that focuses more on self-actualization rather than an indigenous culture threaded with communal connections.

Jaenette Goseyun, a resource navigator at the Phoenix Indian Center who participated in an early test of marketing for the 2020 census, said the message didn’t speak to her values.

“A lot of the advertising didn’t reflect our viewpoints, saying things like ‘I, I, I.’ Their slogan (in Maricopa County) is ‘I count,'” Goseyun said. “There were 14 Natives there, a lot of them came from reservations and hadn’t lived in Phoenix for long, plus we all came in with our own experience, but that was one thing we could all agree on.

“It doesn’t translate how ‘I’ helps ‘we.’ If I feel like I’m just one Native in this big metropolis, then this is not really going to count anyway. If you feel alone, it’s easy to dismiss the census as not being that important.”

Olivia Hendricks, a workforce specialist at the Phoenix Indian Center who also took part in the focus group, said the Census Bureau’s marketing should put more emphasis on how the headcount benefits indigenous people.

“Our main reason for participating should be generating new services for the Native community,” Hendricks said.

Critics also said the bureau’s concerted effort to encourage people to fill out the 2020 census online also does not serve Native populations well.

The Navajo Nation Reservation sprawls over more than 27,000 square miles in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, which present challenges to transportation and offers limited access to the internet and other modern advancements.

Washines was skeptical of the “online first” approach when it came to counting American Indians. He said better roads and bridges and more stable broadband connections are needed.

American Indians in urban areas also will have technological challenges.

“When we look at our Native population living in Phoenix,” Hibbeler said, “the whole idea that technology is the main way to collect data for the census this year is going to be difficult.

“Through our programs and services at our center, we do some ‘basic 101′ to get around the computer and how to use it. We’re still having to help people get an email address and know how to check it. Filling out the census electronically is really going to be difficult for a large portion of our population. A lot of them are low income, so they don’t have those resources.”

In late May, a Navajo census group pushing for a “complete count” traveled to Daniel Piaso’s remote home in New Mexico to hear first-hand testimony about such challenges on the Navajo reservation.

Commission members, accompanied by Census Director Steven Dillingham and Census Bureau tribal partnership specialist Arbin Mitchell, traveled 12 miles on dirt roads to Piaso’s home, west of To’Hajiilee. He speaks only Navajo, as do many elderly residents on the reservation.

“They do not trust strangers who might approach them asking questions about the census,” Mitchell said, according to a statement from the Navajo Nation Council.

Additional challenges, Mitchell told the visiting census officials, include access to decent roads and transportation, lack of broadband and phone connectivity, and difficulty determining mailing addresses.

The American Indian population today

The Native population is surging in Arizona and across the U.S. , which includes 573 federally recognized tribes that need to be counted, the National Conference of State Legislatures reported.

The 2010 census – the one that undercounted American Indians and Alaska Natives by nearly 5% – put the number at more than 5 million. Census-affiliated demographers expect that population to double within four decades.

Phoenix has the largest growing American Indian population of any city. The 2010 census estimated about 130,000 American Indians live in Phoenix, the nation’s fifth largest city.

Counting on solutions

Native American communities have formed “complete count commissions” to address the potential undercount. Debbie Johnson, the director of the Arizona Office of Tourism, leads a 23-person commission to establish outreach to various demographic groups.

Firethunder, the tribal outreach liaison for the commission, said new efforts by the governor’s Office of Tribal Relations to get a complete count include census-branded lapel pins for Indian Health Service and urban Indian health providers to wear as they interact with hundreds of patients each day.

They also plan to work with tribal leadership to film tribe-specific marketing messages during Indian Nations and Tribes Legislative Day on Jan. 15. The event celebrates unique contributions by American Indians to the state and U.S. governments.

Washines said community outreach needs to be extensive.

“I think localized complete count committees are the best way to ensure things are accurate,” Washines said. “There could be a bigger focus on mobile census centers, like buses that travel throughout communities. Public libraries could be a place to go, ‘Hey, bring your library card and you can be counted for the census.’ Focusing on the kids is important, too. The more kids are counted, the better schools can be.”

The Navajo Nation’s Complete Count Commission met for the first time in May.

The commission did not respond to requests for comment, but according to the council’s May statement, the group discussed the significant undercount in 2010 and methods to avoid a repeat in 2020.

Hibbeler said the Phoenix Indian Center is developing an urban campaign in Maricopa County, working with the Indian Center in Tucson and Native Americans for Community Action in Flagstaff.

“We’re going to develop a campaign to reach out to urban-living American Indians based on trust in the census,” she said, “talking about what some of the questions are and letting them know how the data will be analyzed, and how that count really filters into dollars for services and programs in the area where you live.”