WASHINGTON – Arizona lawmakers questioned administration officials Wednesday on what they are doing to deal with the problem of missing and murdered indigenous women – and they weren’t always satisfied with the answers.

Officials with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the departments of Justice and Health and Human Services said they’re trying, but are often hampered by a lack of funding and inconsistent record-keeping when it comes to crimes against Native women.

“A missing person report that comes in isn’t necessarily a crime when it’s reported to one of our police departments out there, so we have to treat those with more … more of a response,” said Charles Addington, deputy director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Office of Justice Services.

But Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Phoenix, told witnesses he was frustrated with what he described as inaction on the part of the BIA – noting that Addington’s testimony Wednesday was an almost verbatim repeat of written testimony from a December Senate hearing on the topic.

Lawmakers also used the hearing as a platform to push for reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act. Rep. Grijalva, D-Tucson, asked witnesses point-blank about its impact on their individual agencies, and all said resources from VAWA would go a long way toward helping them address the problem of missing and murdered indigenous women.

“Nobody wants to get into public safety anymore,” said Addington, who faulted low funding and increased competition over a decreasing pool of qualified applicants for his department’s trouble recruiting and retaining officers.

“We advertise a position where we usually get 15 or 20 people on an applicant list, where now we’re maybe getting one or two,” Addington said.

Rep. Deb Haaland, D-N.M., who advocated for the law during the hearing, later told a rally outside the Capitol that, “We know that VAWA keeps women safe.” She called on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to “put reauthorization to a vote in the Senate now.”

-Cronkite News video by Heather Cumberledge

At the rally, organized by the National Congress of American Indians and the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, Rep. Tom Cole, R-Okla., said weaknesses in tribal law enforcement are one reason Native women are often targets of violence.

“Hunters know where to hunt, fishers know where to fish and predators know where to prey,” said Cole, himself a member of the Chickasaw Nation.

Cole said non-Native predators will intentionally go after Native women because they know there’s a low likelihood of them being caught. Statistics from NCAI show that non-native criminals are behind 96% of the attacks on Native women.

Haaland said eight of 10 indigenous women will experience some form of violence in their lifetime, and witnesses said during the hearing that Native women are 10 times more likely than other women to be murdered.

Witnesses spoke to the need to get better data on missing persons cases to help police develop strategies to both solve those crimes and to prevent indigenous women from being murdered or going missing in the first place.

The BIA only has jurisdiction over lands on tribal reservation, so it’s difficult to handle cases when they don’t have accurate data as to where the person was taken, Addington said.

Both he and U.S. Attorney for New Mexico John Anderson talked about using NamUs, the decade-old National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, to help gather data and solve missing persons cases that have long since gone cold.

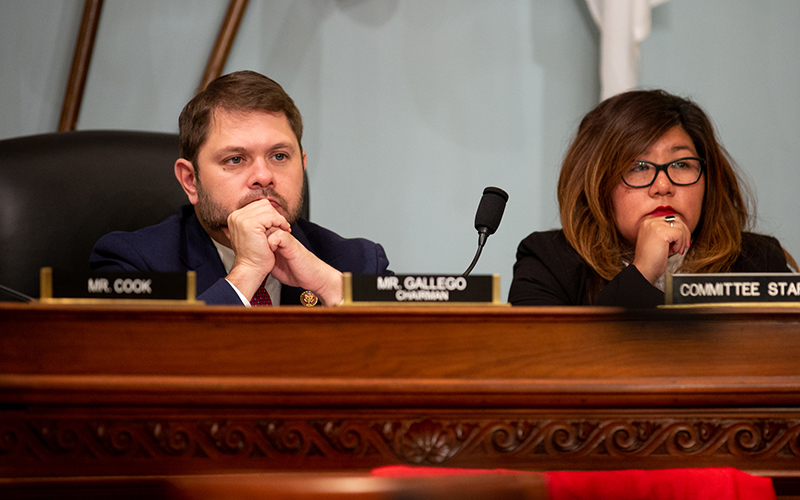

Rep. Ruben Gallego, D-Phoenix, listens as agency witnesses describe their efforts to address the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women. (Photo by Harrison Mantas/ Cronkite News)

NamUs collects missing-persons data from participating law enforcement agencies across the country and offers logistical support to agencies struggling with cold cases.

Addington said BIA began collecting reports of missing persons from tribes in 2013, but when pressed by Gallego on whether that data would be included in NamUs, he said his agency had not collected detailed data.

“We just collected numbers from the tribes. Like missing person numbers,” Addington said. But he added that “working with NamUs, we can add those specific fields and we can actually determine what their tribal affiliation is.”

Addington said having this data will give his agency a better idea of where to focus its resources. It has also expanded training to Indian Country police departments to help them respond to missing person cases, he said.

But women at the rally said there is still much to be done.

Oglala Sioux Vice President Darla Black shared her story of becoming a law enforcement officer after surviving domestic violence. That experience is what led her to a 28-year career in law enforcement, to help women like herself, she said.

“I moved from a victim, I became a survivor,” Black told an enthusiastic crowd at the Capitol. Then she added, as she described the conditions that led to her abuse, “Nothing today has changed.”

Gallego said after the hearing he believes that change may be coming, saying that both the administration and Congress are starting to focus on the issue.

“I believe both on the Democratic side and the Republican side … they understand the urgency of this,” he said.