TEMPE – Adults and children as young as 4 huddle around a painted-over canvas on the grass of Tempe’s Svob Park on a cloudy afternoon. Some of the amateur artists, who were there as part of an Arts in the Parks event, stand close to the canvas, spray cans in hand. Most are inexperienced with graffiti art: They shake their cans before spraying a line or two, examine their work, and then shake and spray again.

Pchit, psst, goes the spray as clouds of color hover over the canvas. Clink-clink, goes the can as it is shaken. The layers of paint begin to build into art.

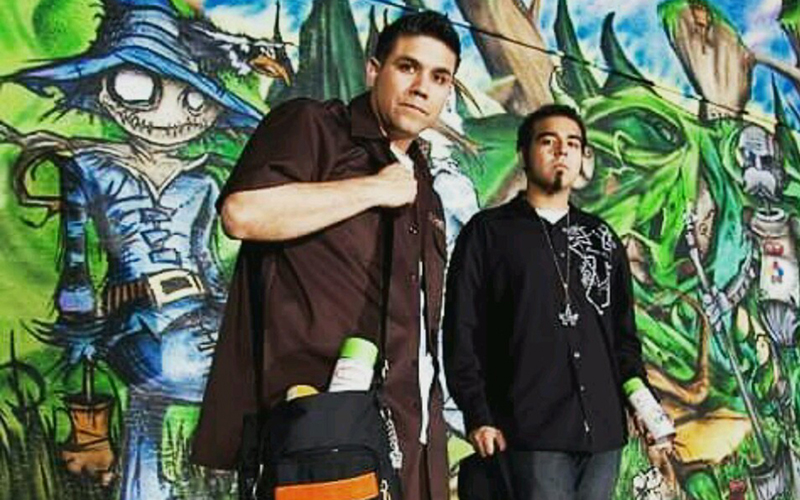

Noe “Such Styles” Baez and his son, Champ, oversee the event, each sporting a well-worn black overshirt with matching pants that blend as if they’re wearing jumpsuits. Their artistic names – “Such” and “Champ” – are stitched in a white patch on the left side of their shirts. Such wants the two of them to have a clean, uniform look. Such can be a little particular about these things.

Father and son believe their graffiti art is rooted in the paint Such used to work with when he started the craft in 1983 – industrial-grade, high-pressure paint that was seemingly uncontrollable and quick. Friends and fellow artists consider the two to be the first – perhaps the only – family graffiti team in Arizona. They have painted on public walls, train cars, internationally and locally, in places such as the Phoenix Art Museum, Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum and Musical Instrument Museum.

“Do you want to try it out, mija?” Such asks a young girl with flowing chestnut hair and a mustard-yellow shirt.

Every young person is “mijo” or “mija” to him, affectionate Spanish terms for son and daughter.

“Go over to your parents and ask them to give me a thumbs-up so I know it’s OK,” he tells the girl. A few moments later, she returns and Such sees her parents give the thumbs-up.

“Here you go, kiddo,” Champ says, offering the girl a blue can of spray paint that she uses to create her best rendition of a flower.

Champ, 27, often executes the one-shot freehand, getting his design done in a single try and in one fell swoop while Such, 50, sketches lines and applies strokes of spray paint again and again, until whatever is in his head emerges.

“It’s like clay,” Such says. “I’m building it, and I know where it’s going.”

Champ echoes his father.

“You’re not really painting with the spray can, you’re sculpting with it,” he says. “Even with the spray can as a tool, it’s probably the one thing that’s going to fight you the most.”

While a paintbrush, marker or pencil makes direct contact with a surface, there is no such connection with a spray can. Champ’s spray can constantly hovers above the surface, designing in the air what the ink will sculpt once it lands. He knows, and his dad knows: That spray can demands respect.

Art-purposed spray paint, which doesn’t fight against the artist but delivers in a neat, modern fashion, can be found in practically any arts store these days. The special low-pressurized notch allows for more control and the opportunity to create embellishments and cover more ground.

But Such, who has been at his craft since the early ’80s, remembers that it wasn’t always this way.

An art, an artist take root

South Tempe, 1983. Noe Baez remembers lying as a teen on the floor of his room looking through the artbook “Getting Up,” a history of New York City subway graffiti published in 1982 by Craig Castleman, a college professor at the time. He looks at the pictures and can’t believe what he sees: Kids just about as old as him, risking a run-in with the cops for the love and bragging rights of leaving their imprint on subway cars – vandalism to the police, but, to them, a form of artistic expression. His eyes scan the pages, as if he were watching one of his favorite after-school cartoons.

He is hooked.

The term “graffiti writers” is imprinted on his brain. He loves what the words do to him; as if they have unearthed a purpose for all the hours and work he has put into tracing comic-book characters so he could learn to draw with style.

In his mind, graffiti writing is like the way of the Jedi: a calling, a way to see the world in an entirely new fashion. The only tool is the spray can.

The back of Champ’s workshirt, with his name woven into the graffiti-style design, at Svob Park in Tempe. (Photo by Alexis Alabado/Cronkite News)

He takes a can from his dad’s garage and sets out to work on an alley wall in his neighborhood under the veil of night. Baez saw the New York street artists doing renditions of Howard the Duck, a Marvel Comics character. He sketched out an image inspired by the character and tries to replicate it on the wall, pressing down on the top of the spray can and getting to work.

Baez – he would not adopt the artistic name “Such Styles” until 1989 – references the sketch in his right hand. With his dominant left hand, he finds out that he can paint, putting a frowning character with a little tilted crown he named “The Devious Duck” on the wall.

From his earlier childhood in South Phoenix, where rival gangs roamed his neighborhood, Baez learned “cholo” scripts – what he describes as Chicano penmanship with an artistic quality – and even sprayed such expressions as “south side” on walls and fences. But this was the first time he had created something more like the East Coast graffiti documented in “Getting Up,” the kind that felt more artistic. And it was the first time he did it without caring about what others thought of it.

About that time, building projects were coming to completion in the heart of Phoenix: the Civic Plaza with its convention center and symphony hall; a Hyatt Regency and the new Adams Hotel, which would become the Renaissance Phoenix Downtown Hotel; and towers for three big banks operating in the state at the time. At the same time, major retailers and small businesses were moving out of downtown or closing their doors, while a new crop of young artists moved in, turning long-vacant buildings – from storefronts to small warehouses – into workspaces.

Back then, according to longtime Phoenix artist Pete Petrisko, graffiti was more nuisance than art. Murals didn’t dominate historic buildings, and pretty much the only artists around were the punk-rock musicians who bled into the 1980s from the 1970s. The general public that had been exposed to it resisted it. To the police, graffiti artists were vandals committing a misdemeanor.

Graffiti was still not considered an art form, and it was not yet seen as a cultural asset. But that was about to change.

A family affair, a growing acceptance

Some dads play catch with their sons. The Styles family painted.

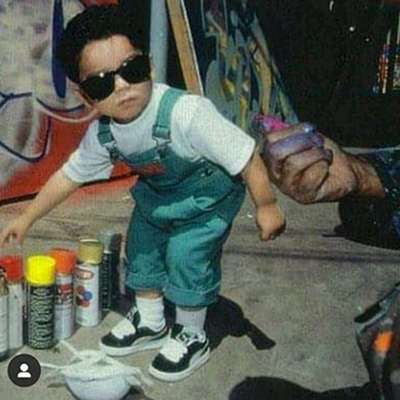

Spray paint was just another part of daily activities for little Champ, from when he was a toddler. He would get up, play with his Thomas the Tank Engine train, and then wander into dad’s room to line up every one of the spray cans there.

Champ, born in 1992, thought every kid knew what graffiti was. As a child, his playground was the railyard, where his dad and fellow graffiti artists practiced their work. Such always told Champ and his youngest son, Christian, that they were free to choose their interests, but Champ grew more interested in the craft as he got older.

A young Champ Styles in 1994, already getting his hands dirty and his heart into the family craft. (Photo by Martha Cooper, courtesy of Such Styles)

He wasn’t officially initiated into graffiti until 2003, when he entered fifth grade. From there, Such describes taking Champ under his wing in a Mr. Miyagi “wax on, wax off” kind of way. Training was done in the backyard, with Krylon paint on a panel of corrugated metal, a challenging combination: The surface made it hard for paint to land without dripping, and the commercial-grade paint was hard to control.

When Champ threw his cans across the yard in frustration, Such would turn off the backyard lights and tell Champ he was painting by the moon’s glow that night.

But with that training, when the time came to paint on real walls – nice brick surfaces, using fancy low-pressure paint with petroleum levels that allowed it to stick, unlike the old Krylon – the chaotic training in his backyard meant that Champ had an edge.

Although he once spray-painted a letter of the alphabet a day, Champ was now recreating characters by Vaughn Bodē, the Walt Disney of the hip-hop and graffiti world, like Cheech Wizard and Lizard. As he grew older, his technique evolved into clever pieces, changing as the city around him changed and, with it, people’s perceptions of graffiti.

Such’s creations were traditional, clean and relatively non-controversial, but Champ’s were youth-oriented and more daring, such as his signature “hands through eyes” collection of famous animated characters like Pink Panther and Wile E. Coyote.

The construction of Talking Stick Resort Arena and Chase Field on the southern edge of downtown forced out artists who had adopted that part of the warehouse district for their work. By the early 2000s, artists began converting commercial properties around Roosevelt Street into arts-related businesses, such as MonOrchid gallery, MADE and Eye Lounge. Coffee shops, restaurants, bars and other non-gallery businesses began to emerge. Commissioned murals began to appear on the sides of buildings, a trend that exploded in the next decade with artists like El Mac, Breeze and Lalo Cota.

At the same time, some well-known murals were lost to construction and demolition. Ted DeGrazia’s and Lauren Lee’s Roosevelt Row murals were lost during the construction of the apartment complex iLuminate. Efforts to preserve the untitled collaboration of El Mac and Augustine Kofie at the Flowers building on Roosevelt and Fifth streets, after a patio was built around the mural for a new restaurant, were derailed after an unknown vandal defaced the mural.

In 2006, Arizona State University’s downtown campus and the Valley Metro light rail brought major changes. Luxury high-rise buildings began to rise downtown, replacing older buildings that had been a canvas for graffiti murals. Some of these murals carried cultural relevance, with desert- and Mexican-inspired scenes. Others had a more whimsical character. A lot of them have been preserved, but not all.

Such Styles inspects his son’s rendition of a llama from the popular video game Fortnite at the March event in Svob Park in Tempe. (Photo by Alexis Alabado/Cronkite News)

Greg Esser, an artist and founder of Roosevelt Row Community Development Corp., says that while sports were an important economic driver, attracting more people and businesses to downtown Phoenix, it was the arts that gave it a strong sense of community.

Such remembers a time when he could get in trouble making art, and police would come around to question him. Today, when graffiti artists can earn commissions for their work, this doesn’t happen much. Graffiti, he says, is “a vehicle of communication to the youth, and I think that’s why industries are using it now.”

But the work from those who started graffiti writing in the ’80s – a time before acceptance, before an artist could get grants for graffiti, before people wanted to pay money for it – is gone. These walls are dust now. That doesn’t seem to bother Champ.

“We’re not attached to anything,” he says.

Eyeing the next generation

As dusk approaches at the park in Tempe, the paneled canvas is a collection of color. From the amateurs, streaks of vibrant reds, deep blues, springtime pinks, and sunset yellows, oranges and purples layer the canvas. The pros offer renditions of Darth Vader, Homer Simpson, Nintendo’s Mario and the Iron Giant, the 1990s animated sci-fi hero. At one point, Champ executes the one-shot of a kid favorite, the Fortnite llama.

Such steps forward to analyze Champ’s creation – it looks like a piñata. He stares at it in silence, his spray can at the ready to make any corrections.

“I think that’s good,” Such says with a curt nod of approval.

At one point, a boy no older than 12 walks by with his mother, his features mirroring a younger version of Champ. He has on a navy hoodie, the hood pulled over his head, and a quiet demeanor. His dark eyes scan the canvas in interest.

Noe “Such Styles” Baez, who trained his son Champ in graffiti art, shows a young amateur how close the can needs to be to the canvas to paint effectively during a public event at Tempe’s Svob Park in March 27. (Photo by Alexis Alabado/Cronkite News)

“Do you wanna try it out, mijo?” Such asks.

With some prodding, the boy eventually gathers his courage and chooses a spray can from Champ. He positions himself in front of the canvas, which is a little taller than him, and begins spraying in the left corner. He spray-paints “Champ” in neon orange, adding a three-pronged crown over the letter “a.”

“You write my name better than I write my own, brother,” Champ says. “This your first time doing this?”.

“Yeah,” the boy says, his head perking up.

“You know, you could make a lot of money doing this.”

“Really?”

“Looks like we got a natural,” Such chimes in. “He’s quick, he’s got that style – he’s got the look too.”

By the end of the night, the boy – his name is Jose – has exchanged Instagram accounts with Such and Champ Styles and instructs a friend who had tried her hand at spray-painting too, sounding as if he’s been painting all of his life.

“You wanna get close to the canvas when you spray; if you’re too far, the paint will just splatter, but if you’re close, you’ll have more control …” he tells his friend.

Father and son watch the scene unfolding before them: The next generation taking on the mantle.

“Fine art is nice; it will always belong in a gallery and it’s meant to be put on a pedestal. But now, graffiti art – graffiti itself in its rawest form – is the one art form that is in a place where it’s not supposed to be there,” Champ says.

“You walk by a piece on the street with some funky characters, a sweet background and some nice letters, and instead of admiring it, that piece will grab you by the collar and tell you, ‘Look at me. Ha, ha. I’m here, whether you like it or not. And I may disappear, but I will always be back,'” he says. “It demands your attention. Find me another art form that does that.”

He later acknowledges, jokingly, that he’s starting to sound like a radical.

From one generation to the next, Champ, left, stands with his father, Such Styles, in front of some of their most recent work. (Photo courtesy Such Styles)