Iesha Harper and her fiance, Dravon Ames (center) have filed a $10 million notice of claim against Phoenix in connection with a May 27 police stop. (Photo by Tanner Puckett/Cronkite News)

Protesters, proponents and the cultural clash over Phoenix police

By Tim Royan/ Cronkite News |

PHOENIX – A preschooler reportedly takes a doll from a dollar store. Police surround her parents’ vehicle in a sun-soaked parking lot, guns drawn. One officer threatens, with an expletive, to shoot. A head is slammed against a police car; legs are kicked apart. Onlookers videotape the scene, murmuring disapproval.

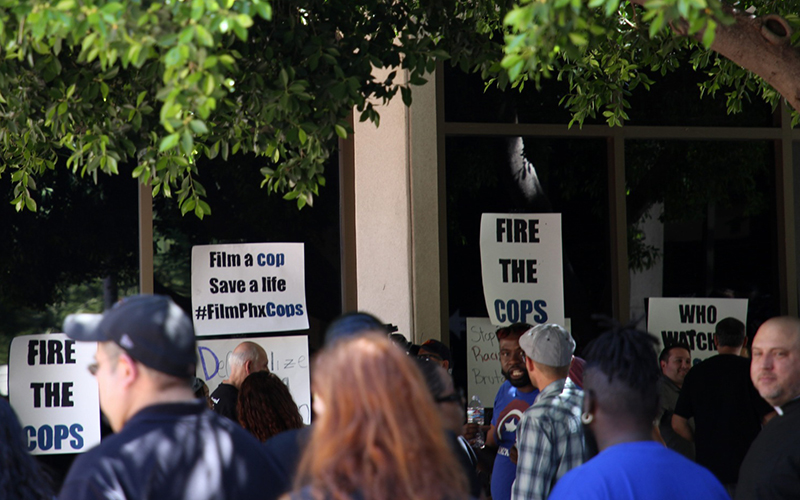

A video goes viral. Changes are demanded, debated, promised. Insults and accusations are exchanged by police supporters and police reformers. Sides entrench in dueling points of view and distrust mounts.

“I feel like there is a core fundamental problem with policing,” said Parris Wallace of Poder in Action, which advocates for changes in public systems and policies.

The May 27 stop of Dravon Ames, his fiancee, Iesha Harper, and their two young children was fuel dumped on smoldering coals of tense relations between the public and Phoenix police. The viral video sparked new – and rekindled long-standing – outrage over accusations of overaggressive policing of people of color, while it hardened the resolve of police supporters.

“We see it much differently than the other side; those police officers did their job,” said Nohl Rosen, who founded Rally for Law Enforcement in 2014. “They should be commended and thanked for it rather than condemned.”

Ames and Harper have filed a $10 million notice of claim against Phoenix in connection with the incident shown in the video, which circulated amidst an ongoing push locally and nationally for police reforms inspired by a growing awareness of the police shootings that made the names Michael Brown, Philando Castile and Tamir Rice nationally known.

Police departments have looked to technology for solutions, such as body-worn cameras to monitor police and public behavior and early-intervention software to sniff out bad behavior. Experiments with better community engagement, including civilian review boards with subpoena power, also are being considered or field-tested. Phoenix police plan to launch accountability procedures to document every time an officer draws a gun.

The Phoenix department also has faced criticism over officer-involved shootings and allegations of overzealous policing in recent years. Last year, Phoenix officers fired their guns at people 44 times, more than any other U.S. police force and almost twice as many as New York City’s, according to azcentral.com. At a rally for President Donald Trump in 2017 – a week after the murder of a young antifacist protester in Charlottesville, Virginia – Phoenix police hurled flash grenades and tear gas and fired rubber bullets and pepper balls into a crowd of protesters, allegedly without warning.

Police representatives and community advocates have said law enforcement is unjustly maligned and misunderstood – to the point that Tempe police officers were asked to leave a local Starbucks because another customer felt uncomfortable.

Body-worn cameras

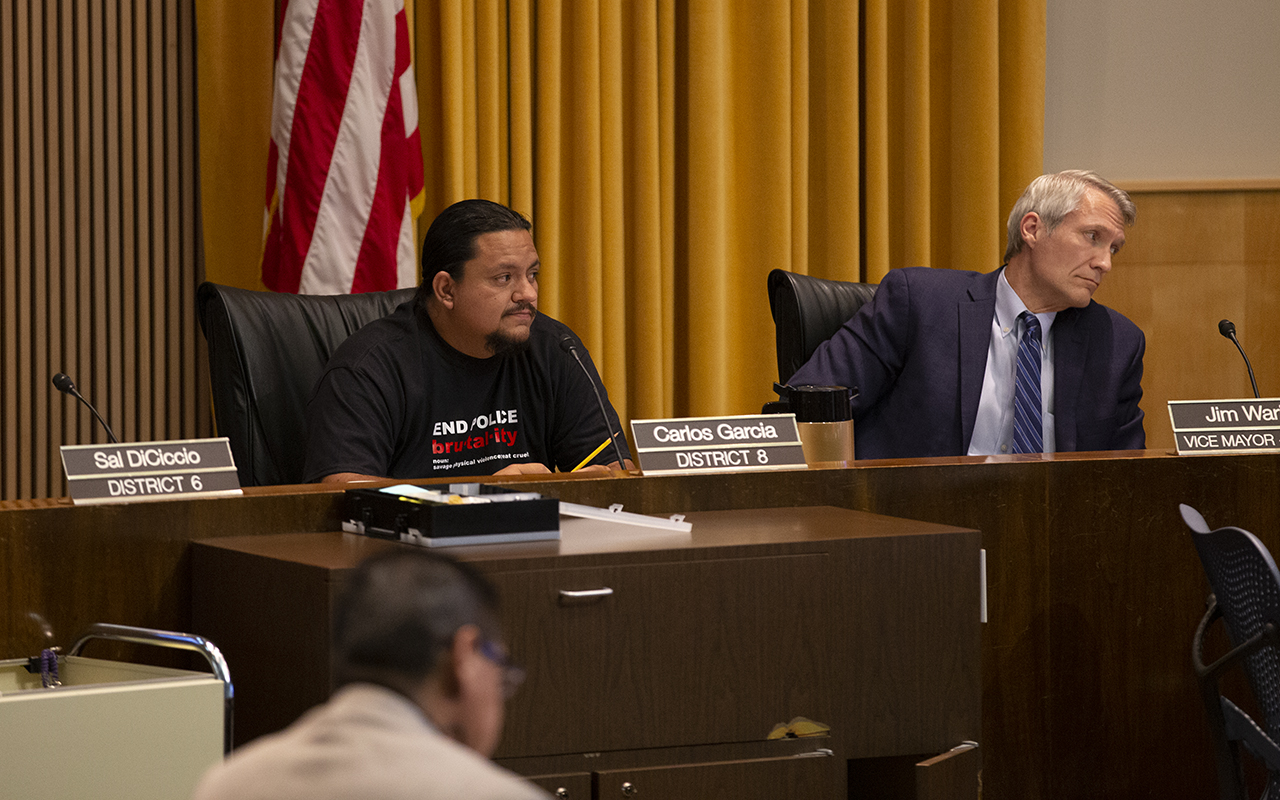

The Phoenix City Council is the arena in which most police-reform battles have been fought. Veteran Councilman Sal DiCiccio has positioned himself as a staunch defender of police, while newcomer Carlos Garcia, who frequently attends council meetings wearing a T-shirt that reads “End police brutality,” was elected on a platform of reform.

In February, the council approved a five-year $5.7 million contract with Axon, formerly known as Taser, to outfit its officers with body cameras. All 2,000 front-line officers are expected to have the cameras this year, according to police representatives.

However, Phoenix police have flirted with body cams for years – the original $500,000 pilot program issued the technology to officers in the Maryvale neighborhood in 2013.

Body-worn cameras are one of the few reforms in which police, most council members and activists on either side of the issue agree.

Although the rollout began before the stop of Ames and Harper, the incident increased pressure on authorities to deploy the cameras. In a June 19 City Council meeting, reaction to the incident led to hours of concerned comments from some members of the public, many of whom demanded the cameras as a check on police.

Xenia Orona questioned why body-cam footage and police reports could not be made immediately available.

“It should be as easy as checking a Twitter feed,” she said.

Police officials also embrace the cameras.

“There’s some people out there saying, ‘Well, this is an opportunity for us to to monitor the police officers,'” Sgt. Tommy Thompson, a police spokesman, said in July. “Yes, but it’s also an opportunity for the police officers to be able to present what they see as their perspective.”

Rosen agrees. He initially was hesitant about body cameras, but viral cellphone videos purporting to show police misconduct in recent years have changed his mind.

“The body cams have actually been a very good tool to combat the other side’s narrative,” he said. “It’ll show what the officers actually had to go through at that moment in time.”

Poder in Action, which is a party to a lawsuit alleging police violated the First Amendment rights of the protesters outside the 2017 Trump rally, have pushed for the cameras for years. But Wallace is under no illusion the technology will curb what she calls police overreach.

“What we look at, as far as the body cameras go, is they provide a sense of closure for the families,” she said. “It’s not going to change the violence, it’s not going to reduce violence, it’s not going to reduce any of the criminalization that’s going to happen.”

At the council’s February meeting, Police Chief Jeri Williams, the first black woman to hold the job in Phoenix, assured that, at a minimum, an officer will receive a written reprimand for failing to turn on his or her camera at the proper time.

Thompson said the cameras won’t always be recording.

“There may be some case occasions when they turn them off,” he said. “Obviously, if I go to the restroom, that would be a time I’d want to turn the camera off.”

The city’s contract includes 2,000 cameras, data storage and access to Evidence.com, which is software Axon provides to manage the footage, including tools to aid in redacting sensitive details, such as license plates, police computer screens and people who are not suspects.

Axon representative Jason Hartford said the redaction tools use algorithms that automatically blur anything within the range of human faces and skin tones. This allows police personnel charged with redacting videos to avoid hours of frame-by-frame editing and expedite releases to the public, courts and media.

Facial recognition stirs controversy. Critics have argued that police could use footage from body-worn cameras for facial matching – identifying people by matching their face to others in a database – or for warrantless surveillance.

Some cities already use facial matching technology. New York has been building a database containing the faces of people as young as 11, with little oversight, The New York Times reported.

The Axon software uses facial recognition for redactions, but the company does not offer facial matching, the company says on its website.

In the absence of government standards on facial matching, Axon funded an ethics board. The board in June unequivocally opposed use of facial matching and recommended Axon not adopt it in its current form, citing the technology’s inability to perform equally across races and ethnicities, genders and ages. In addition, the board strongly opposed any face recognition that could be completely customized by the user, fearing misuse by law enforcement.

When Axon’s redaction tools were mentioned at the City Council’s February meeting, council members asked Williams whether her department was using any other form of facial recognition technology. Phoenix does not utilize any form of facial recognition technology, Williams replied, and there are no plans to implement it in the future.

Poder in Action, whose mission, according to its website, is “to build power to disrupt and dismantle systems of oppression and determine a liberated future as people of color in Arizona,” supports the use of body cameras, but there’s an acknowledgement that the cameras alone won’t suffice.

“There’s no justification to have them if there’s not a strong policy in place” to prevent misuse of the cameras, such as facial matching or warrantless surveillance, Wallace said, adding, “Using it for immigration purposes, identifying for that sort of thing, that is a concern.”

A Phoenix police spokesman did not respond to requests for an interview about body-worn cameras and other proposed police reforms. Williams has voiced support for her department’s first-responders but has publicly spoken about the need for police reforms.

The vast majority of officers are good, the chief has said, but “any unprofessional behavior reflects on everyone in the police department. There are thousands of police employees who do not deserve this perception.”

Policing the police

Civilian review was the most contentious reform discussed this summer by the City Council. No decision has been made, and the matter will be addressed further when council meetings resume in September.

The council is considering several variations of a civilian review board as an independent body to look into allegations of police misconduct. Councilman Garcia has been vocal about implementing a civilian review board with subpoena power, but options are on the table.

Police departments in more than 100 U.S. cities have some form of civilian review board, including half of the largest police forces, according to a city staff report prepared for the council. Various “tipping points” were cited as catalysts for civilian review in these cities; in Atlanta, for example, it was the shooting of a 92-year-old woman. The staff report was prepared in March, before the viral stop of Ames and Harper.

The City Council is reviewing three types of review boards using standards from the nonprofit National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement: review-focused boards; auditor/monitor boards; and investigations boards.

A review-focused board relies on a police department review to draw an independent conclusion. An auditor/monitor board looks at trends and spikes in data to identify issues in the force and make recommendations. An investigations board has subpoena power and disciplinary authority.

Boise, Idaho, and Pittsburgh use investigations boards, which is the model supported by Garcia, Wallace and other local critics of law enforcement.

“We need a community review board that is going to include citizens, that’s going to include experts, victims and that’s going to have subpoena power,” Garcia said at a June 18 council meeting.

In practice, the review boards become hybrids, said Liana Perez, director of operations for the association.

“I can tell you no two cities are created the same,” she said. “Sometimes there’s a model that will have an auditor with a board attached to it or a monitor and a community board as well.”

Each model comes with benefits and downsides.

The auditor/monitor boards, for example, are typically cheaper, needing fewer staff members and resources, Perez said. But such boards often are composed of volunteers, who don’t always have enough time to dedicate to every investigation.

“A lot of people feel that the full investigative model is probably the one that’s more supported by the community because they know that investigations are completely being taken out of the police department,” she said. “The downside to that is it’s very resource and financially intensive because then you have to create a full investigative body with investigators, usually attorneys.”

And then there are the legal obstacles.

“Subpoena power is kind of hard to come by,” Perez said. “Even if it is put in there, it’s often times difficult to go forward with it because it gets challenged immediately by the police unions.”

Newark, New Jersey, faced that challenge in trying to set up such a board, Perez said, and they “have not been able to even open their doors as of yet.”

Perez said cities often scramble to create civilian review boards after a troubling incident, but haste comes with downsides.

“Usually the ones that are created as a result of something bad happening … are less successful: ‘We were created under this model, with this level of authority, but that’s not what we needed. We needed something else.'”

When the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement was founded 25 years ago, Perez said, police officials rarely interacted with the group. But it’s working alongside departments more and more these days, especially over the past decade, she said, crediting the increased scrutiny on police incidents and to the effectiveness of civilian review boards.

Law enforcement agencies tend to warm up to the idea of civilian review once they “understand it’s not an adversarial role that the oversight entities are taking on, that the community is being represented and all complaints are fair and thorough,” Perez said.

Still, she understands there will always be resistance.

“I think that there’s probably still a lot of naysayers out there that are on the other side saying that the oversight entities are anti-police,” she said. “That’s really not the role that, at the professional level of oversight, that we take at all.”

For Wallace and Poder in Action, an investigations board is the only option to actually hold police accountable.

“All of the time that they spend investing in equipment and more officers and implicit bias trainings – all of that energy could be focused on the community itself,” Wallace said.

Community investment includes such programs as parks and recreation and libraries, Wallace said. For her, these programs serve the people better than police.

“We’re looking at safety past policing: Safety, meaning access to jobs, access to job training, access to living wages in those communities that are most directly impacted,” Wallace said. “That doesn’t mean putting 300 more police officers on the street … safety looks like being able to safely wait for the bus with a covered bus stop, lighted streets … a lot of different things that don’t include policing or being overpoliced.”

Reforms to hold police accountable

The City Council also is looking into other policies and methods to better hold police officers accountable.

In the wake of the Ames and Harper video, a special meeting of the council was held July 2 to look into early intervention software to track and measure police conduct, along with a proposed survey of community attitudes toward police and a civilian review board.

The council voted 7-1, with Vice Mayor Jim Waring dissenting, to research companies that could provide early intervention software. Phoenix police already use a variation of such software, but it isn’t as comprehensive. Most council members were enthusiastic about the “increase in data” that would be provided by an early-warning system flagging worrisome patterns in an officer’s record, such as repeated complaints or use of force.

Waring expressed concern that the newer software would prove a disappointment.

“I’m just afraid we’re going to be here a year or two years from now and the goal won’t be achieved for some reason,” said Waring, who had earlier pointed out the existing software had promised to address the same issues. “I want to make sure we don’t just waste money on something that’s not going to accomplish the goal.”

Garcia was in favor of the system but stressed it was only a small part of the overhaul needed by law enforcement.

“If we don’t fundamentally change the way we look to involve community and actually address this issue with the urgency that it needs, then these systems are for naught,” Garcia said.

A cultural chasm

For Wallace, the underpinnings of the police force are inherently corroded.

“The culture of policing is rooted in violence. It’s rooted in racism. It’s rooted in all of those things that we talk about as an organization” she said.

Police culture took centerstage in June after the Plain View project compiled a database of offensive social media posts that included posts by Phoenix officers.

Some of these posts, Williams said in a statement, eroded the trust the department is trying to establish.

“It’s a good day for a choke hold,” one post said, seemingly in reference to the high-profile 2014 death of Eric Garner, for whom a police chokehold proved fatal. Another congratulated George Zimmerman for “cleaning up the community one thug at a time” after he was acquitted of murder for his role in the 2012 death of Trayvon Martin in Florida.

The Phoenix Law Enforcement Association responded with an announcement that it was looking into technology to help officers “scrub” their social media history.

The erosion of trust Chief Williams pointed to was exemplified in a Tempe Starbucks when a barista in July asked six police officers to leave because a customer felt unsafe. This led to a social media uproar, demanding a boycott of Starbucks using the campaign #DumpStarbucks.

For police supporters, the cultural chasm is most present in threats made to law enforcement and their supporters.

A week after the council approved the police department budget despite the ire over the Ames and Harper video, another council meeting drew police supporters. In a meeting where DiCiccio’s pro-police statements elicited cheers instead of boos, the threats were brought up before the council.

Through tears, police dispatcher Andrea Max told the council about threats she had received on the job, including threats to kill her family. Police later released examples of these threats, which DiCiccio posted on his Facebook page.

Rosen, founder of Rally for Law Enforcement, said backlash to his positions led to fake Google reviews of his business, threatening messages on Twitter and name-calling.

“People were calling me a racist. They were calling me a Nazi,” he said. “Of course, that one makes me laugh, being Jewish.”

The next round

When the City Council reconvenes in September, the first phase of the body-worn camera is expected to be completed. Research into the early intervention system will progress and a new tool for identifying patterns of police misconduct eventually will be approved or rejected.

The debate over civilian review boards will continue, but it’s unclear whether a review board will be implemented at all, let alone one with subpoena and disciplinary power.

As for how the council should make this tough decision, Perez of the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement echoes Councilman Garcia.

“Part of the process has to also be very inclusive of the community because, ultimately, you’re going to end up with some kind of a balance,” she said. “You should consider not only the needs of the community but also how it affects operations in your city structure.

“To be as inclusive as possible with all the stakeholders that are affected as you create the entity is important.”

Follow us on Instagram.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]