PHOENIX – The press release that went out on July 6, 1969, began: “The United States will launch a three-man spacecraft toward the Moon on July 16 with the goal of landing two astronaut explorers on the lunar surface four days later.”

That astronomical task, which was stated in the plainest of terms, would be completed only 14 days later, eight years after President John F. Kennedy set the goal to send astronauts to the moon before the end of the decade.

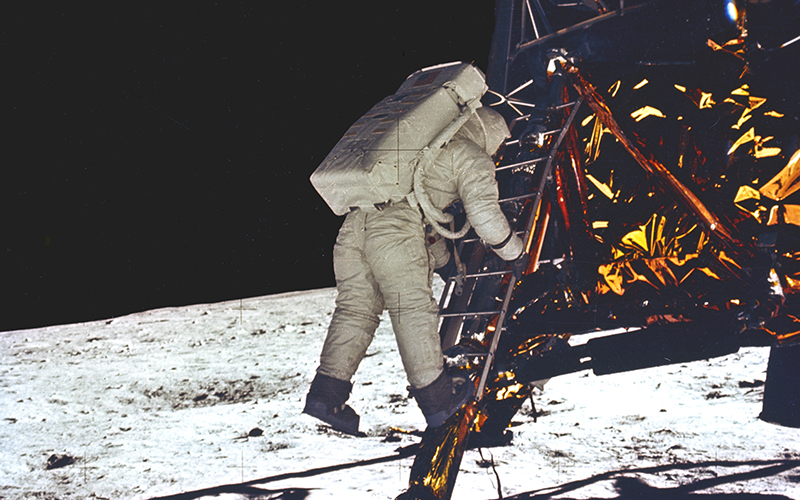

As many as 600 million people watched worldwide, in some cases clamoring for a glimpse in a Sears display window, as Neil Armstrong descended the ladder of the Eagle and became the first human being to touch the powdery surface of the moon. Buzz Aldrin, close behind, was the second.

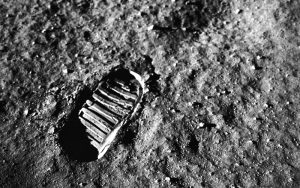

Because the moon has no atmosphere or wind, the footprints left by Apollo astronauts, if undisturbed, will likely never lose their shape. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

But before Armstrong and Aldrin touched down on a dusty, rocky volcanic surface 240,000 miles from home, they traversed a more familiar dusty, rocky volcanic surface for practice: Arizona.

Arizona scientists and educational institutions have since assisted with a number of NASA missions, and as science continues to peel back the layers of the cosmos, Arizona’s involvement in these projects only seems to deepen.

“We’re (ASU) pretty much covered throughout the solar system,” said David Williams, deputy lead for the imager and co-investigator with the science team of NASA’s Psyche mission and associate research professor with ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

The Psyche mission is a journey to an asteroid that orbits the sun between Mars and Jupiter. Williams also was involved with the New Horizons mission to geologically map Pluto and the Cassini mission to map Titan, one of Saturn’s moons.

For Jim Bell, deputy principal investigator and camera investigation lead with Psyche and professor with ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration, the might of modern space technology makes the first Apollo mission almost unbelievable.

“They went to the moon with the computational power of a key FOB for your car,” Bell said. “Everything has changed. So it’s actually incredible that they did that in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s without people getting killed.”

In the 50 years since Apollo 11, humanity has extended its reach over 13 billion miles from Earth, almost 57,000 times farther than the Apollo 11 crew traveled. Scientists discovered the first exoplanet in 1995 and have confirmed the existence of more than 2,000 more since then.

Bell said the mapping work done by robotic missions like the 1966-67 lunar orbiters is what made the Apollo journeys possible. Those early robotic explorers also set the groundwork for such projects as Psyche, which seeks to map and collect data about the asteroid’s unique geology and formation.

‘A stark beauty all its own’

The earth at Cinder Lake Crater Field in Flagstaff once was pocked with craters formed by dynamite blasts, meant to simulate the moon’s terrain. There, Apollo astronauts from multiple missions practiced lunar exploration from the comfort of their home planet. Many of the craters have since been worn down or filled in through natural weathering and use of the field as a recreation site.

Apollo 15 astronauts David Scott and James Irwin ride “Grover,” a lunar roving vehicle simulator during geology training at the Cinder Lake crater field in northern Arizona. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

Astronauts also practiced in Sunset Crater, Meteor Crater and Hopi Buttes Volcanic Field. One group took a two-day hike to the base of the Grand Canyon to practice studying an area’s geology.

The astronauts and NASA scientists who visited Arizona were assisted by Gene Shoemaker, a Flagstaff geologist who is considered the “founder of astrogeology.” He founded the Field Center in Flagstaff along with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Branch of Astrogeology.

A number of major Arizona institutions boast current and past staff members who had a hand in the Apollo missions.

Similarly, General Dynamics Mission Systems, a Scottsdale-based company, also built the radio transponders used in pre-Apollo missions and were responsible for broadcasting Armstrong’s iconic first steps on the moon.

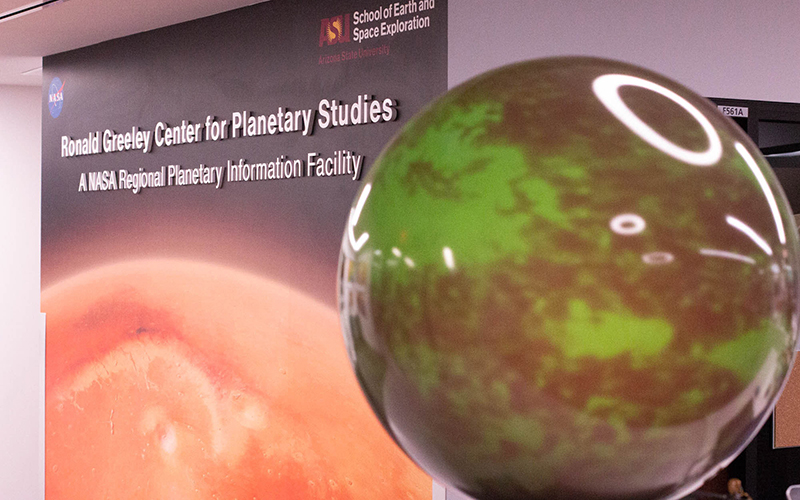

The rock and dust samples collected by Apollo 11 were studied extensively by Carleton Moore, who founded Arizona State University’s Center for Meteorite Studies in 1961 and served as its first director. Ronald Greeley, a regents’ professor of planetary geology at ASU, helped map lunar landing sites and train astronauts.

University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory was founded in 1960 by Gerard Kuiper, the “father of modern planetary science.” Kuiper conducted research with fellow UA professor Ewen Whitaker involving the moon’s geography and was involved in robotic lunar explorations that paved the way for the Apollo 11 moonwalk.

The ‘giant leaps’ of mankind

“In terms of instrument technologies – electronics and computers – everything has changed dramatically over 50 years,” said Alfred McEwen, principal investigator of NASA’s HiRISE mission and director of UA’s Planetary Image Research Laboratory. “It’s a totally different world.”

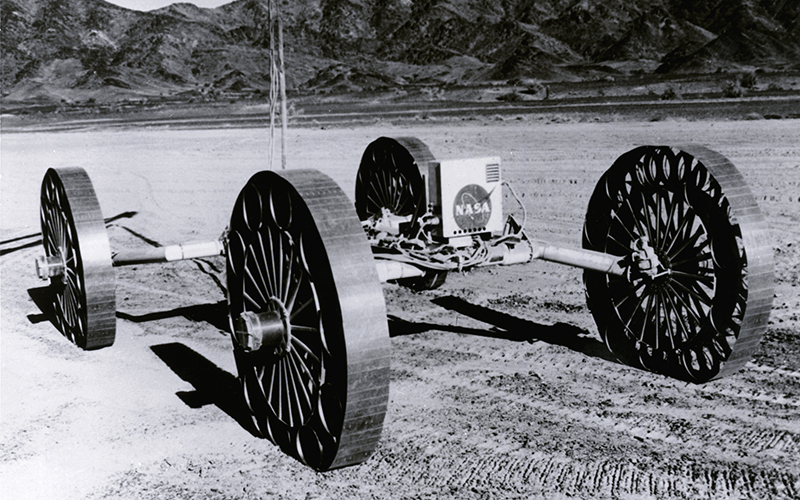

Test vehicles were driven over rocks in northern Arizona meant to simulate the moon’s uneven surface. These test drives helped NASA design the lunar roving vehicle, or LRV, which Apollo astronauts used during exploration missions. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

HiRISE is another robotic mapping mission, focused on photographing the Martian terrain.

McEwen said the Apollo astronauts not only photographed the moon, they had to chemically develop the photographs while in space and scan the pictures back to Earth, where they again had to be developed. Nowadays, he said, everything is done digitally.

Another major difference between the Apollo missions and space exploration today is that almost all modern missions are robotic. Apollo 17’s Eugene Cernan in 1972 was the last man to set foot on the moon, or any other extraterrestrial object.

Williams said the choice to land humans on the moon was a political decision in the first place.

“Sending humans to the moon was a political goal to basically show U.S. economic and scientific and engineering dominance and basically to beat the Soviet Union there,” Williams said. “Once we accomplished that with the Apollo mission, then public interest waned.”

Bell said robotic missions’ data now will come in handy if NASA decides to send humans to another celestial body, the same way those initial lunar mapping missions helped the Apollo astronauts.

“While nobody’s planning specifically to go to Psyche the asteroid, some day – decades from now, centuries from now – someone’s going to go there and they’re going to need the mapping data and the environmental data, physical properties, et cetera, that missions like our Psyche mission will provide,” Bell said.

Although McEwen said there are other, more interesting places in space to explore than the moon, Williams remains hopeful that human feet will again kick up dust on the lunar surface.

“Could you learn the entire geology of the earth if you only landed at six places on the surface?” Williams asked. “The moon is quite diverse and there’s an awful lot that we can learn about the moon. So there’s a great impetus to go back and do that.”

The moon still has much more than geological samples to offer humanity, he said, including resources for everything from building materials to resources used in making rocket fuel.

Williams said the next step in exploring the moon is something NASA calls the Lunar Gateway, a spaceship that will orbit the moon and act as a “temporary home and office” for future astronauts exploring the moon and Mars. This, he said, could be an action that saves humanity from mass-extinction.

David Williams, an associate research professor at ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and deputy lead for the imager with NASA’s Psyche mission, says Arizona’s involvement in space exploration goes beyond the Apollo 11 mission. (Photo by Grayson Schmidt/Cronkite News)

“The only reason the dinosaurs aren’t here is because they didn’t have a space program; they couldn’t deflect that asteroid that hit the Yucatan Peninsula 65 million years ago that wiped them out,” Williams said. “To ensure humanity’s survival, we should become a space-faring civilization and live in multiple places throughout the solar system, and the moon being the closest place to the earth – it’s only three days away – is the one that makes the most sense to be the starting point for that.”

With SpaceX and other companies working with or even rivaling NASA for intergalactic real estate in the future, McEwen said space travel’s new place in the private sector can benefit exploration efforts that may be bound by the “bureaucratic nightmare” NASA faces as a government institution.

Whatever the source, Bell said space exploration still acts as a uniting force for America, the same as it did in 1969.

“I think it’s great that it’s one of the few areas left in our government where the parties can come together and say, ‘Hey, you know what? This is good for the country. This is good for the world,'” he said. “And that’s really encouraging and exciting.”

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.

AlertMe