PHOENIX – First, the needle’s sting. Then the blood, flowing from the vein into a plastic testing card, the membrane unit.

The waiting begins.

This morning, inside the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS in downtown Phoenix, the client’s heart beats faster than the steady tick of the clock. The deep-blue rubber tourniquet that had snapped into place against his clammy skin now rests on a gray countertop, limp like a deflated balloon. By a metal sink in the corner of the small square room, a neon-orange trash bag yells “BIOHAZARD.” An HIV tester in khakis and a white button-up shirt hunches over the desk, awaiting the results.

It only takes 60 seconds to find out whether you are HIV positive.

Nearly 30 years after the AIDS epidemic reached its peak, contracting HIV – human immunodeficiency virus – no longer is a death sentence. Most people who receive a positive diagnosis can live long and healthy lives, and the risk of HIV transmission has plummeted nationwide with the help of new medications and the regular use of condoms.

Despite these advances, pockets of HIV contamination persist, devastating lives and communities across the country. And certain regions – poorer and heavily minority urban parts of the United States and rural areas, where infections are driven by the increase in opioid addiction – are more at risk than others.

Of the nearly 3,000 counties in the United States, 48 account for about half of HIV occurrences, or the number of newly diagnosed infections each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These “hotspots” include Los Angeles and Maricopa counties.

Cookie King, a case manager at the Southwest Center, says her HIV status has been “undetectable” since 2008. King understands the fear, shame and isolation of the virus, and she knows what it’s like to neglect taking care of yourself. (Photo by Sarabeth Henne/Cronkite News)

Maricopa County, the fastest-growing in the nation, ranks 44th on the list of HIV hotspots, according to a 2017 CDC surveillance report. A supplemental report by the Arizona Department of Health Services, released last year, notes that about 71 percent of the state’s HIV cases in 2017 occurred in Maricopa County.

Of the 6,726 people living with HIV/AIDS in this region, 432, or about 6 percent, were diagnosed in 2017. And, as in every other county on the hotspot list, Latino and black men are disproportionately affected.

Arthurine “Cookie” King spends her work days helping a lot of these men, comforting them, holding their hands. She understands what it’s like to be HIV positive. She understands the fear, shame and isolation of the virus. She knows what it’s like to live with so much shame that you neglect taking care of yourself.

King believes that she should be dead. In fact, she has almost died three times. But now that she has saved herself, she is helping save others.

On this spring morning, King enjoys the balmy breeze on her face as she ambles down the sunbaked streets of downtown Phoenix on her way to work. She turns onto Portland Street and enters the Parsons Center for Health and Wellness, a sleek modern building that houses organizations that serve people living with HIV/AIDS, including the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS, where she works and where anyone can be tested for free.

King’s goal is to ensure that her clients become undetectable, meaning that the viral load of HIV in their blood is low enough to not be picked up by monitoring tests. Although the clients will always be HIV positive, the virus is nearly impossible to transmit to others at this level. King considers herself a resource center and tries to establish a friendly rapport with her clients. She “fills in the blanks” for them, she said, whether through providing information about HIV, finding them a place to live or calling to check in on them.

When she returns in the evening to her home in south Phoenix, a part of the city where roughly 1 in 8 residents is a minority, she enjoys the company of her 19 dogs, all rescues of varying breeds and sizes, who greet her with enthusiastic barks and wagging tails.

King, 60, is a willowy woman who favors gratitude over grief. Clad in sage-green pants and a patterned tunic that billows behind her like a kite in a strong wind, she glides down the halls of the Southwest Center, her caramel skin glowing under the warm yellow lights, her chestnut hair a muddied waterfall cascading down her back. When she passes, people turn their heads to look.

The staccato click-clack of her heels against the vinyl floor and the way she keeps her chin up exude the kind of confidence and poise that is often seen on catwalks.

She doesn’t have a college degree or a car. But she does have an aptitude for empathy, which is crucial for her job.

King has worked at the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS since 2011 as a supportive case manager. In a place that treats thousands of Arizonans with HIV each year, her job is to serve as a navigator for those who have been positively diagnosed at the clinic. She does not get involved in any of their medical care. Instead, she ties loose ends by providing resources for her clients: transportation, housing, scheduling for counseling sessions and nutritional, dental and pharmacy referrals. Some of these can make the difference between life and death.

“My job is to walk with you and hold your hand until you can do it on your own,” King said. “I am your mailman, but I won’t open your mail for you.”

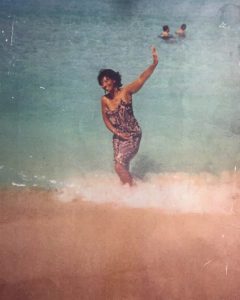

After a year in treatment for HIV and substance abuse, Cookie King returned to the waters off South Beach in Miami in 2001. (Photo courtesy of Cookie King)

She was born in St. Louis and raised in Toledo, Ohio, by her parents, who were Jehovah’s Witnesses. She went to Bible study twice a week, and on Sundays, the family attended services at the Kingdom Hall.

“We were very nurtured (but) sheltered,” King recalled. “I promised myself when I got out of high school, I was going to party like a rock star.”

That’s just what she did – and that’s when her life began to unravel.

In 1981, she left Toledo for Washington, D.C., where she became homeless. She then moved to Miami, where, in 1985, she was diagnosed with HIV while living on the streets. She does not know how or when she contracted the virus, but suspects it could have been from her time as a prostitute in Miami or when she shared needles with her then-boyfriend, who was HIV positive.

“I immediately went to, ‘Not me, I’m an Afro-American heterosexual woman,'” King said, adding that back then, HIV/AIDS was called “the gay man’s disease.”

“I immediately thought they got my blood mixed up with someone else’s,” she said.

For the next 15 years, King ignored her diagnosis and continued earning money as a prostitute to feed her drug habit. As an intravenous drug user, King mistook many of the classic HIV indicators – fever, muscle ache and fatigue – with the flulike symptoms of drug withdrawal.

In 2000, her family found her in Miami, still on the streets, and brought her to Phoenix, where she enrolled in a rehab program that specialized in people with HIV. For the next several years, she focused on her sobriety, speaking at Narcotics Anonymous meetings and sharing her story. During this period, she got a job at Ebony House, an Arizona nonprofit that works with people with substance abuse issues, behavioral challenges and HIV/AIDS. It was there she interacted with other people who were positive and was put on the Southwest Center’s radar.

“Because of my life experience, I’m able to help a lot of our clients in the community,” King said.

Tom Mickey, the sexually transmitted disease program manager for the Maricopa County Public Health Department, said in an email that minority populations are disproportionately affected by STDs and HIV infections “due to lack of access to health care resources and existing cultural suspicions of certain health care options.”

Ben Van Maren, an early intervention specialist at the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS, says Maricopa County’s proximity to the border helps fuel the spread of HIV. (Photo by Sarabeth Henne/Cronkite News)

Ben Van Maren, an early intervention specialist who works with King at the Southwest Center, agrees. He said the county’s rapid growth and its proximity to the border – where people come from many “different backgrounds, different cultures” – present ideal conditions for the fast spread of HIV.

“With so many people, it’s easy to be anonymous,” Van Maren said. “You’re like a pebble in a river.”

HIV can spread rapidly in densely populated communities, epidemiologists say. The virus is largely transmitted through unprotected sex or when drug users share infected needles. Although most people are equally susceptible to the virus, Latino and black men who live in impoverished areas have proven more prone to contracting it.

Among the main reasons for high prevalence of HIV are the social stigma and discrimination that surround the virus. Van Maren said that even when volunteers and employees from the center bring their traveling clinic to black and Latino communities with high rates of the virus, many are hesitant to be tested, whether it be for fear of ostracism or trepidation about discovering their status.

“There’s also this aspect that both of those communities tend to be religious and a lot of religions do not talk about HIV or sexual health,” Van Maren said. “It can be really difficult for organizations like us to go in those communities and have a productive conversation.”

Many infected people who live in these areas do not have easy access to places where they can get tested. They also may not have the money – or insurance – to pay for the tests, or they don’t think they’re infected. In its 2017 report, the CDC reported that 16 percent of Arizonans who were HIV-positive were not aware they carried the virus.

Because they don’t know or don’t want to face the truth, people with HIV continue to engage in risky behaviors that put others at risk. In just a matter of months, the rates of HIV can skyrocket in a community, as it did in Austin, Indiana, in 2015 when the small town became the epicenter of the worst drug-fueled HIV outbreak in rural America.

Surges can also occur in urban areas, where minorities have some of the highest incidences of HIV. According to the Arizona health department’s 2018 HIV surveillance annual report, non-Hispanic blacks in Maricopa County had the highest incidence of HIV, with a rate of 35.5 per 100,000 people. That’s more than double the rate of Hispanics and six times the rate of whites.

HIV rapid tests like this one are commonly used in the Southwest Center’s outreach programs to determine whether someone carries the virus. (Photo by Sarabeth Henne/Cronkite News)

This trend is easy to spot at the Southwest Center. Lisa Fontes, the center’s director of development, said about two people are diagnosed with HIV every week at the clinic, where 40 percent of the clients are white, 35 percent are Hispanic and 16 percent black. About half are 25 to 39, and 80 percent come from “low income and nearly half live at or below the federal poverty level,” she said.

“HIV does not discriminate,” Fontes said. “Geography is the Number One factor for your risk of HIV.”

This is because people are most likely to get HIV from someone in their social network, which usually depend upon location and proximity.

“It’s unlikely that if you live in Queen Creek, which has a pretty low HIV incidence rate, that you’d get HIV, compared to if you lived in Glendale or south Phoenix, which have higher incidence rates,” Fontes said. “There’s a geographic barrier to having interaction between the social networks.”

Rachel Howard, an epidemiologist with the Maricopa County Public Health Department, said geography also determines how much access one has to information and education about sexually transmitted diseases and HIV, which, in turn, lowers their motivation to seek care.

“Knowledge is power,” Howard said. “It’s important for people to understand and recognize the health concerns that are impacting their community.”

There are many reasons for the discrepancy between HIV prevention reaching black and Latino men across different hotspots. Some of them are intangible, such as cultural barriers that make conversations about sex at the very least uncomfortable and the stigma against same-sex relationships. Other reasons are practical, including access to health care.

In an interview, Damien Salamone, an associate professor with a background in molecular and cellular biology in the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University and the executive director of HEAL International, a nonprofit that provides health education and support for people with HIV/AIDS, talked about another critical factor: the disparity in the access and quality of health care in poorer communities

“If a person gets access to health care and they get access to high quality health care, then they can get an HIV test and they can get access to treatment,” Salamone said. “And once they are receiving treatment for HIV ( a regimen that slows the progression of the virus by reducing the HIV viral load in a person’s blood) they can’t transmit the virus to others.” In other words, they become undetectable.

Arthur “A.J.” Dominguez is in charge of the IGNITE Your Status project, a volunteer-driven community outreach program that seeks to normalize the conversation around safer sex and HIV by distributing materials, hosting testing events and providing education and assistance with pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. (Photo by Sarabeth Henne/Cronkite News)

Arthur “A.J.” Dominguez is currently undetectable, but he traveled a long, difficult road to arrive at this point. In 2009, in the depths of his addiction to crystal meth, he was diagnosed with HIV at the Southwest Center’s former location, then called Body Positive, in north Phoenix.

“It came back positive, and I ran out of the place,” Dominguez said. “All I thought about at the time was that I was going to die.”

Dominguez said he was so lost in his addiction at the time that he did not seek treatment for HIV. After two stints in prison for his drug use, however, he was forced to make a decision about his future.

“A light turned on,” he said. “I was either going to die from my addiction or die from not taking care of my health, so I decided to ask for help.”

During a bartending shift, he met volunteers for IGNITE, a community outreach program from the Southwest Center. Dominguez slowly built a relationship with the director of the program, who encouraged him to interview for a position at the center. He was offered the job in June 2017 and now manages IGNITE, helping people who carry the same burdens as he once did.

Soon after landing that job, he began to work with “Cookie” King.

“Her being so open and sharing her past, that helped me to share my story,” Dominguez said.

Like Dominguez, much of King’s success at the center is her ability to empathize. Each day, she watches dozens of people leave their families or partners in the waiting room while they get tested for HIV.

Some clients are in the testing room for up to an hour and leave with a relieved smile, lighter, as if a burden had been lifted from their shoulders. Others emerge shell-shocked or with tears streaming down their faces.

King feels a connection to those who receive a positive diagnosis.

“It’s one of those moments where you say, ‘You are my people. You do understand. You know what it’s like,'” King said. “People that are diagnosed today get to live a full productive life … and I’m that incentive and motivation to other people.”

King said that she is a completely different person from who she was when she was diagnosed with HIV 34 years ago. She owns a home, has been sober for 19 years, and finds fulfillment in helping others who are walking the path she has walked. Although she will always carry the virus, she has been undetectable since 2008.

King tells her clients that HIV saved her life because it forced her to make healthy changes and choices.

But not all of her clients see it that way. And that, she said, often is the most difficult part of her job.

“Most challenges are when people come here and don’t want to do the work or live behind HIV or they feel like their lives are over,” King said. “Getting someone to think outside the box is challenging.”

Connect with us on Facebook.