PHOENIX – Baltimore and Phoenix are two completely different cities culturally and geographically, but they’re both experiencing the same problem: increased deaths due to opioid overdoses, specifically those involving fentanyl.

From June 2017 to April 2019, there were a little more than 2,800 suspected opioid deaths and just more than 20,500 opioid overdoses in Arizona, according to the state’s Department of Health Services. In Baltimore, there were 692 opioid-related deaths in 2017 alone, the city’s Health Department.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Maryland issued a statement in 2018 projecting there would “be more than 2,000 fentanyl deaths statewide, and in Baltimore alone there are projected to be at least twice as many fatal fentanyl overdoses as homicides.” Statistics for the full year have not yet been released by the state’s Department of Health.

Last August, however, the Baltimore City Health Department announced an experimental method of preventing more opioid related deaths by actively distributing fentanyl testing strips at mobile syringe and needle exchange sites to “test the(ir) efficacy.” Maryland decriminalized the testing strips as part of a “harm reduction” bill in June 2018.

“We was getting a lot of overdoses, as you know, it’s an epidemic all over the country and we were seeing quite a few overdoses here in the city,” said Derrick Hunt, program director for Community Risk Reduction. “And so that was another tool to use that could possibly save some lives.”

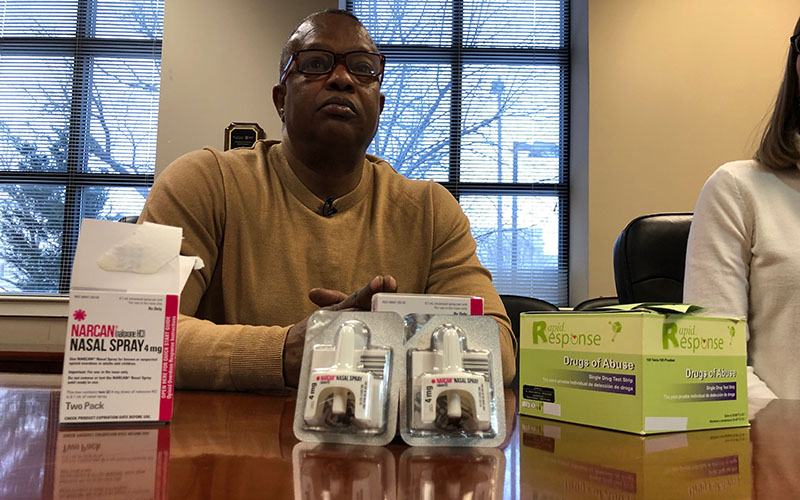

Narcan nasal spray, also known as naloxone, and fentanyl testing strips are just two of the harm reduction materials the Baltimore City Health Department distributes to drug users. “First and foremost, one of the purposes of harm reduction is to help save a life today so that you can save a life tomorrow,” said Derrick Hunt, program director for Community Risk Reduction in Baltimore. “And some of that is through the provision of naloxone and … fentanyl test strips.” (Photo by Bryce Newberry/Cronkite News)

The low-cost strips – similar to those used in home pregnancy tests – are able to detect the smallest traces of fentanyl laced into drugs, but they can’t assess how much, according to the Harm Reduction Coalition.

In Arizona, those strips still are considered “drug paraphernalia” under state law, as they fall under the heading of materials that “test and analyze” illicit drugs. Anyone possessing them would be committing a Class 6 felony, according to the law.

The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office declined to comment for this article, saying only that “the office has not analyzed the issue,” a spokesperson for the office said in an email.

Haley Coles, executive director of Sonoran Prevention Works, a grassroots group that aims to educate people about harm reduction methods, strongly believes state-sponsored programs, like those in Baltimore, would be vital to reducing opioid-related deaths in Arizona.

“Our state has done a lot of expansion of overdose prevention, which has been really, really helpful,” Coles said. “But part of the missing piece is programs like syringe service programs where we can really on a large scale reach people who are at risk for unknowingly consuming fentanyl and dying because of it.”

Coles, Hunt and other risk reduction advocates alike point to a study conducted by a health professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which concluded the test strips “were the most accurate at detecting the presence or absence of fentanyl.”

Professor Susan Sherman, who headed the 2018 study, said the evidence overwhelmingly supports legalizing the strips nationwide.

“Having a study that validates it in two crime labs really helps further the arguments,” she said.

“A study like this can be used to inform and change drug paraphernalia laws. I think it’s justified because you know science can inform police and practices.”

Sherman hopes that kind of change happens quickly in Arizona and other states.

“I don’t know why we wouldn’t be (encouraging harm reduction) with this crisis,” Sherman said. “If this were Ebola in this many people, or the flu … think about what the public health and political response would be.”

Professor Susan Sherman of Johns Hopkins University led the 2018 study concluding that fentanyl testing strips were the most accurate method of detecting the deadly opioid in other drugs. “They are very sensitive, but their one flaw is that they don’t tell you the quantity,” Sherman said. “And so it’s really important not to just hand out strips, but to also engage people in conversations – harm reduction conversations.” (Photo by Bryce Newberry/Cronkite News)

The Drug Enforcement Administration describes fentanyl as “a synthetic opioid that is 80-100 times stronger than morphine” and usually is laced into street drugs, including painkillers and heroin, in tiny powdered amounts.

According to the DEA in Arizona, agents seized 172 pounds of powdered fentanyl in 2017 and 445 pounds in 2018, a nearly 159 percent increase.

They also seized more than 95,000 fentanyl laced pills in 2017 and more than 379,000 in 2018, an increase of almost 300%.

Coles said local harm reduction efforts are key to keeping Arizonans alive – despite the taboos.

“There are these larger social structures that are going to take a lot of time and a lot of people to figure out, but right now we have syringes, we have naloxone, we have fentanyl test strips,” she said. “Although these materials make people really uncomfortable, and some people have this perception that you are enabling a person to use drugs or you’re telling a person it’s OK to use drugs – really the message is, I love you and I want you to stay alive.”

There are volunteers across the state who work with organizations like Sonoran Prevention Works to discreetly distribute harm reduction materials – the test strips, clean needles and syringes – to users and potentially re-emerging users.

Cathy, a Mesa resident who wished to keep her identity as vague as possible, is one of those volunteers. She personally puts together harm reduction kits in her home to prevent other families from receiving the call that a loved one has died from an overdose.

“It’s devastating to know that maybe that next phone call that comes in is going to be somebody calling to tell you that your child is dead,” she said. “It’s horrifying. I know moms can’t sleep, they can’t function, and because there’s such a stigma surrounding addiction substance use disorder, there’s not a lot of people that you can talk to about it.”

Alfred Delgatto is a former drug user who works with Sonoran Prevention Works and people like Coles. He drives his van to popular spots for users and offers basic hygiene and living supplies in addition to test strips and needles.

“A lot of it is framed around harm reductions,” Delgatto said. “Making sure that they have the supplies they need to … be as safe as possible when they’re actively using substances.”

He doesn’t think he’s enabling an addiction but rather helping people get on a safe path to recovery.

“It’s not easy for most people to just stop doing everything at once,” Delgatto said. “I think most people thrive in an environment where they kinda chip away at things one thing at a time.”

He finds his work unique in that he is actively befriending the people he meets on a near daily basis and supporting them in their struggles.

“I’m out here with these guys. These are my friends,” Delgatto said. “I think what helps people the most sometimes is having that ear, having somebody out here listening to them and connecting with them.”

Alfred Delgatto volunteers with such organizations as Sonoran Prevention Works to provide drug users with fentanyl testing strips and clean needles and syringes, as well as basic hygiene and living supplies. “It’s not easy for most people to just stop doing everything at once,” Delgatto said. “I think most people thrive in an environment where they kind of chip away at things one thing at a time.” (Photo by Austen Bundy/Cronkite News)

Back in Baltimore, William Miller Jr. serves his community in much the same way as Delgatto, working as a coordinator for BMORE Power, which advocates harm reduction methods and materials, including the testing strips.

Organizations like his, he said, are more than simply providing an environment for safe drug use.

“People need to stop thinking it’s that easy,” Miller said. “There’s other things that are involved also … living arrangements, eating food, jobs, so it’s other things and finding out why a person uses, adverse childhood experiences, so it’s a lot of things. It’s more than just the drug use.”

The experts all agreed that the testing strips should be decriminalized nationwide so their organizations can work out of the shadows.

Delgatto said Arizona’s law listing the strips as “drug paraphernalia” hampers the fight against the opioid crisis.

“We need sensible drug policies – what we have right now are drug policies that cause more damage than drugs do,” he said.

He thinks that instead of putting people away for possessing or using drugs, the government should already be doing the kind of work he and other volunteers do.

“If they’re not going to step up and help, the least they could do is look away when we’re out here doing what the state should be doing,” Delgatto said.

Cathy, the Mesa volunteer, agrees. She said she isn’t afraid to go to jail for helping people.

“If for some reason some policeman comes to me and he said whatever you’re doing is illegal, I would say, fine. Take me to jail,” she said. “At this point, I’m not afraid to be out there with those who suffer from the disease and I will continue to do that until somebody stops me.”

Video and additional reporting by Bryce Newberry/Cronkite News.

Follow us on Twitter.