“If you fill out a paper you can name anybody you want. If you don’t fill out a paper then the state of Arizona tell doctors and nurses who the person is going to be making decisions, and sometimes that might not be who you want for various reasons. This is a way of having control,” said Dr. Patricia Mayer about the importance of advance directives. (Photo by Julio Lugo/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Health care professionals are urging the public to make some of the toughest decisions they’ll ever face for themselves or loved ones: filling out advance directives on whether they want doctors to take extreme measures to keep them alive after a catastrophic illness or accident.

The directives tell health care professionals what patients want for end-of-life care if they can’t speak for themselves, said Dr. Patricia A. Mayer, director of clinical ethics at Banner Gateway Medical Center.

April 16 is National Healthcare Decision Day. About 1 out of 3 adults in the U.S. complete an advance directive, according to Health Affairs.

“People in this country are reluctant to talk about serious health issues,” Mayer said. “They think it’s never going to happen to them. Then, if it does happen and it happens suddenly, then it’s too late to talk about it,” Mayer said.

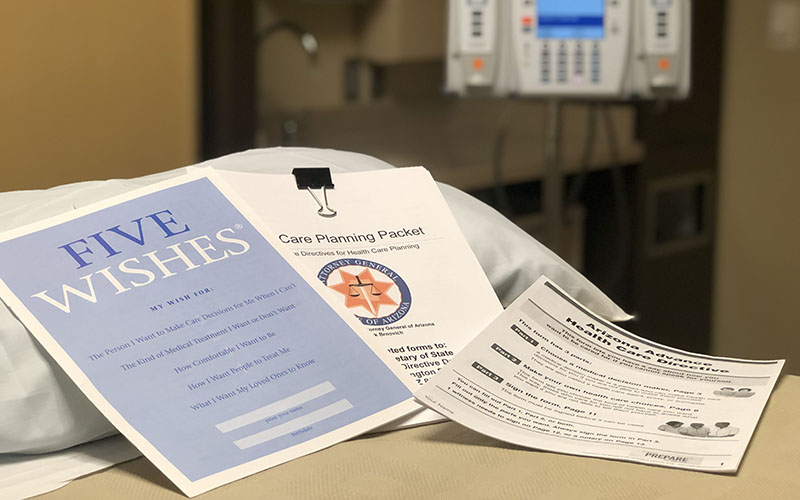

Two of the most common forms of advanced directives, Mayer said, are medical power of attorney and living wills. Free forms can be found online on local government sites to download, print and fill out.

Timothy Biagas recently filled out an advance directive for his 93-year-old mother.”It gives me peace of mind and my wife peace of mind that at least we know we’ll be able to take care of mom the way she wants,” he said. (Photo by Julio Lugo/Cronkite News)

Timothy Biagas recently filled out an advanced directive for his mother, Theresa Biagas, 93. He and his wife are his mother’s representatives.

Timothy Biagas said it wasn’t easy.

“I don’t know if you know anything about older adults, but they’re resistant to change,” he said.

“When we introduced this change and told her it’d be the best for her and for us to help her with her care while she lives here with us, then she finally said OK.”

The documents assure Biagas any decisions made will be in his mother’s best interests. He recommended others make the same preparations.

Neila M. Keener, a palliative-care social worker at Banner, said the default step, without an advance directive, leads health care professionals to rely on a statutory surrogate law in Arizona.

“We have to guess what they want and we have to talk to family members,” she said. “It’s hard on families. It’s very emotional, and it’s very sad because they don’t know what that person wants.”

Keener also said people have misconceptions that advanced directives are expensive or leave the patient powerless.

Mayer said the directives give patients the control.

“It protects the patient because you can imagine that there may be instances where the person the state tells us to go to, might not be the person who knows you the best. They might not be the person who’s best suited to help make those decisions,” she said.

Keener said patients filling out these forms should choose someone they trust, who cares about them and knows their values. The person doesn’t have to be in the same state, just easily accessible.

Biagas recommends that others who are considering doing an advance directive for a family member know what the loved one wants and explain the need. It relieves the stress of guesswork during some of the toughest times for families.

“It gives me peace of mind and my wife peace of mind that at least we know we’ll be able to take care of mom the way she wants,” Biagas said. “It really made us think about some of the future planning my wife and I had put off. We thought about it, but never did it. We thought that, even though we’re younger, we still need to have these in place.”

Follow us on Twitter.