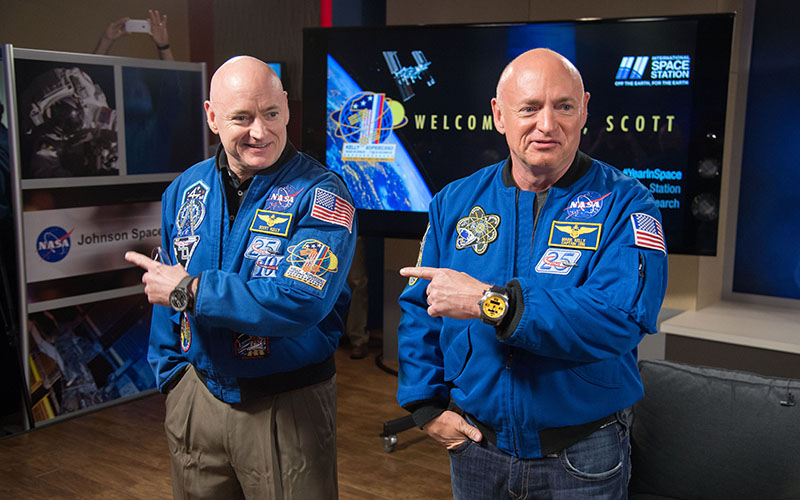

WASHINGTON — Scott and Mark Kelly were identical twins when Scott went into space, but would they be identical when he came back to Earth 340 days later? NASA says yes – eventually.

Long space travel does bring “significant changes” to the human body, but most are reversed a few months after returning to Earth, according to a NASA study released Thursday.

The “twins study” used Mark Kelly – a former astronaut who is now running as a Democrat for Senate in Arizona – as the control for a study of the effects of space travel on his brother, who spent almost a year on the International Space Station in 2015.

Steven Platts, NASA Human Research Program deputy chief scientist, said on a conference call to release the study that the results show “the resilience and robustness of the human body.”

“We’ve evolved here on Earth in a one-G environment,” Platts said, in reference to Earth’s gravity. “Yet, when we go into space and experience microgravity and travel at speeds like 17,500 miles an hour, our bodies adapt and continue to function, and by and large function really well.”

Scott Kelly said his return to Earth was quite difficult, but after about six months he felt better.

“It was significantly different than how I felt after six months, I mean not even in the same ballpark,” Kelly said of his previous trips to space. “My flight was twice as long, I felt absolutely twice as bad, maybe five times as bad.”

One of the most surprising findings for researchers was the change in the length of the telomere, a cap at the end of DNA that typically shrinks with aging or stress. Scott’s telomeres actually got bigger in space. It’s not what they expected, said Susan Bailey, a Colorado State University professor who was a principal investigator of telomeres.

“We proposed that telomeres would certainly shorten more rapidly in Scott,” Bailey said on the conference call. “We couldn’t have been more surprised by what we saw. In fact, Scott’s telomeres were longer at every single time point that we had during the flight.”

But once he returned to Earth, she said, Scott’s average telomere length shortened “very rapidly.” Over the next six to nine months, they were near the same as the start of the study, Bailey said.

Christopher Mason, associate professor at Weill Cornell Medicine and principal investigator of gene expression, said many genes began to change right when Kelly got to space, but that was expected because the human body is “always changing.”

But there were six times as many changes in genes throughout the second half of the trip to space, he said, although the “vast majority,” or around 90% of Scott Kelly’s genes, were back to normal upon his return to Earth.

Dr. Andrew Feinberg, a Johns Hopkins University professor who was principal epigenomics investigator for the project, said “there wasn’t anything that was any kind of red flag” in the findings, but that more study is needed.

“If you just study one twin pair, you can’t really draw biological implications,” he said, adding the study is “the beginning of the era of human genomics in space.”

Mark Kelly – who spent much of 2015 working for gun control with his wife, former Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, while his brother wat in space – said the findings will be important for future generations, as well as a potential trip to Mars.

“It’s great, we saw and learned that the human body is pretty resilient,” Kelly said. “If we decide to go to Mars someday with people, that’s going to be a two-and-a-half year trip, and I hope we do it, I hope we do it soon.

“I hope I get to see it, I’d even be the person to volunteer to go now that we know this about my brother Scott,” Mark said.

Subscribe to Cronkite News on YouTube.