WASHINGTON – Arizona was one of seven states that met with federal officials and veterans groups in Washington this week to map out a strategy for reversing the complex problem of suicides among vets.

The problem is real in Arizona, which had the sixth-highest veteran suicide rate in the nation in 2016, due in part to the state’s aging veteran population and the wide-open spaces that make access to behavioral services difficult.

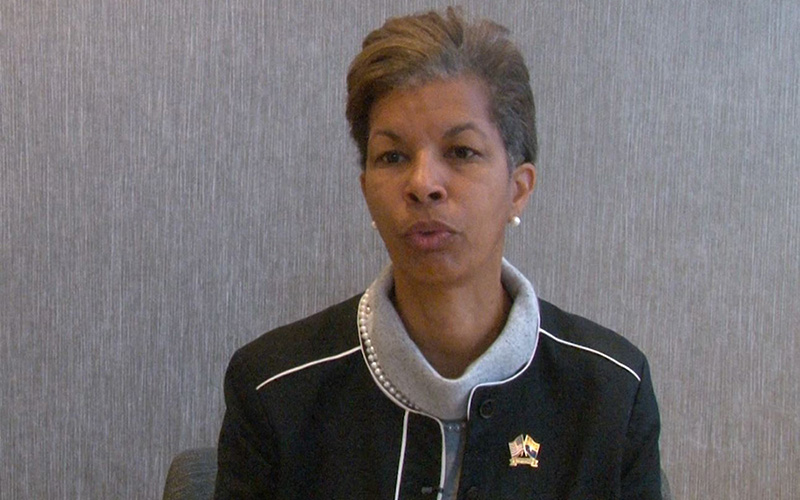

“That’s just terrible,” said Wanda Wright, director of the Arizona Department of Veterans’ Services. “And being in the position I’m in, I felt like I had some influence on that.”

Wright was in Washington as part of the inaugural Governors Challenge to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, a joint effort by the departments of Veterans Affairs and of Health and Human Services. Health care experts, veterans and state and federal officials collaborated for three days to find local solutions to the ever-climbing veteran suicide rate.

In 2016, the most recent year for which the VA has reported data, veterans were committing suicide at a rate of 30.1 deaths per 100,000 vets, compared to an overall national rate of 17.5 suicides per 100,000 people. The numbers were sharply higher in Arizona, with an overall rate of 23.4 suicides per 100,000 and a vets’ rate of 44.1.

The Arizona Violent Death Reporting System claimed an even higher veteran suicide rate of 54.8 per 100,000 in 2016. It said the rates ranged from a high of 90.9 in Mohave County to 39.1 in La Paz County.

Arizona officials at the Washington meeting pointed to several factors driving the state’s high veteran suicide rate.

“We tried to make a correlation between how veterans were dying,” and what officials could do to address that, Wright said. “What we found is that older veterans that have access to firearms – that are in isolated places – they have a higher risk for suicide.”

And residents of rural areas face a lack of access to health care – or to reliable Internet that could bring care to them, experts said. That makes it harder for veterans in rural areas to get treatment during the transition from deployment to home life.

Getting health care providers to rural areas is difficult, said Jill Bullock from the University of Arizona’s Center for Rural Health.

“If you tend to grow your own providers, they come back, but that is not always the case,” Bullock said. “It’s harder to train and get your residency programs out to the rural areas because you don’t have the patient volume that you do in the urban areas to get all of your … requirements.”

That challenge is repeated on tribal lands where the “standard for what basic health care is is lower,” said Kristine FireThunder, executive director of the Governor’s Office on Tribal Relations.

“When you add on a specialty like behavioral health, that makes things even more difficult because they don’t have anyone inside the community to address it … especially in times of crisis,” FireThunder said.

-Video by Luv Junious/Cronkite News

Even if a culturally competent caregiver can be found, she said, turnover undermines long-term care.

“You build a relationship, you build that trust and all of a sudden (they) leave and you’re back to no one to talk to again,” FireThunder said. “You’ve got this baggage of trauma you have to unfold, but nobody’s there to help you unpack that bag.”

Federal officials hope the seven states in the challenge will help them implement a 10-year National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicides that calls for a collaborative approach to the problem at the federal, state and local levels. Wright, a veteran of the Air Force and the National Guard, said local input will be critical to the spread and success of the national plan.

“The VA is a federal entity … but what they’ve come to realize now is that only 30 percent of veterans in the country are engaged with the VA,” Wright said. “So where are the rest of them? They’re somewhere in the community.”