PHOENIX – He holds out his forearm, pointing to an area right below a bandage near the crook of his elbow. One of his veins is much thicker – it looks like a caterpillar under his skin. It’s a fistula serving as the entry port for his hemodialysis treatment.

“It’s like they stitch two of your veins together into a Schwarzenegger vein,” he said, explaining how his doctors created the fistula. He is sitting in the living room of his parents’ modest home in Phoenix. Family pictures and signed baseballs rest atop the TV, where a Spanish-language talk show plays on low volume.

Paul has been on dialysis since he was 2 because his kidneys aren’t able to filter waste, salt and extra water from his blood. Until he was 12, the blood was filtered inside his body, using a special fluid injected through a port in his abdomen. Now, he goes to a dialysis center to have his blood gradually removed, cleaned and returned to his body through the port in his arm.

According to the National Kidney Foundation, patients typically spend three to five years on a transplant list, waiting for a kidney. Paul, who is 21, has needed a kidney for 19 years.

Paul is an undocumented immigrant who has temporary permission to live and work in the United States through an Obama-era program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. It gives certain immigrants who were brought to the country illegally as children a reprieve from deportation; although it allows Paul to access health insurance, his options are very limited.

Immigration status is not supposed to affect transplant eligibility, but insurance coverage and socioeconomic status do.

Paul has emergency insurance through the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, or AHCCCS, the state’s version of Medicaid, that pays for his dialysis but does not cover organ transplants. DACA recipients do not have access to the full insurance marketplace under the Affordable Care Act, and Paul said he can’t afford the cost of private health insurance, even if he were to qualify for it, given his pre-existing condition.

Paul is worried that sharing his story might jeopardize his placement on the transplant list and endanger his parents, who are also undocumented. He agreed to tell his story as long as he and his relatives are identified only by first name.

Racing against time

Every three days, Paul visits a dialysis center in Phoenix to have his blood filtered through a machine. His kidneys failed completely while he was still in middle school, so he has lived without kidneys for over seven years. Because of this, he has to limit his fluid intake to 32 ounces every day.

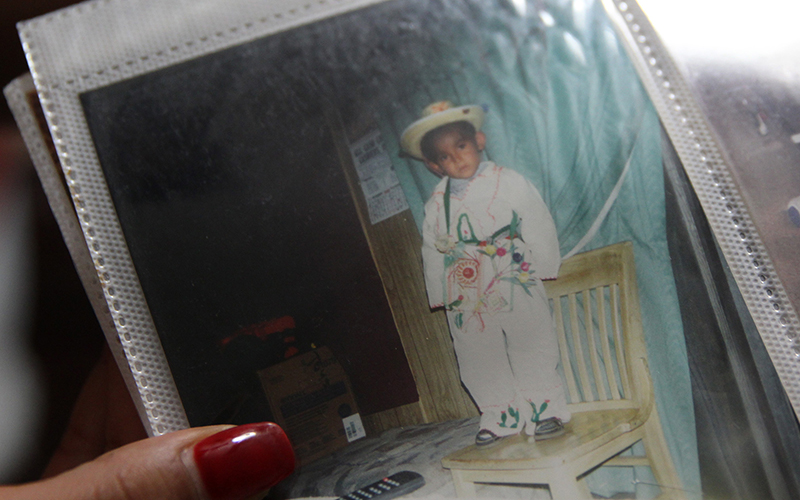

DACA recipient Paul, now 21, was a child when his kidney problems were first discovered. Paul has needed a transplant for 19 years, but he does not qualify for Obamacare coverage as a DACA recipient and can’t afford insurance on his own. (Photo by Rebecca Spiess/Cronkite News)

The hemodialysis will prolong his life, but Paul is racing against time. Twice, he has nearly died. He looks much younger than his age, his 5-foot frame thin and brittle, his large brown eyes often shaded by a snapback cap.

The treatments are hard on Paul’s body. He sometimes sleeps four to five hours after he gets dialysis, and his blood pressure medication has uncomfortable side effects. He recently lost his job at Home Depot because he was feeling too ill to work. College was a plan once upon a time, but he quit high school two months shy of graduation when he realized he was short on credits; he had missed a lot of classes while hospitalized for three months in eighth grade.

There was a time when Paul believed his life would get better, that he would gain a level of normalcy that he has never really known. But the dialysis and the medications, the frustration and the long, long wait he has endured have worn him down.

“I can last up to another 20 to 30 years. There’s no lifespan on the dialysis,” he said. “I just gave up hope already.”

A lifetime of worry

Paul was a baby when his parents brought him across the border from Mexico. They walked for 15 hours through the desert to reach a “ranchito,” a small ranch, near Nogales, Arizona, where the smuggler they had hired had told them to go.

His father began working in construction shortly after arriving in Phoenix. The family wasn’t planning to stay very long, Paul’s mother said. But when her son was 2, she realized that something was seriously wrong with him.

“When I took him to the doctor, they told me that he had pain. Lots of pain,” she told a translator in Spanish. “The following day, they just continued to do more studies, and they saw that his kidneys were small” – too small to do their job as they should.

Paul’s first treatment was peritoneal dialysis, which relies on the lining of the abdomen, or peritoneum, to filter blood. Dialysis solution flows into the area through a catheter and later is flushed out, carrying the impurities that his kidneys couldn’t remove from his blood.

His parents feared that they wouldn’t be able to get Paul proper dialysis treatment in Mexico, so they stayed in Arizona and brought him to Phoenix Children’s Hospital, where he was treated for most of his childhood.

Paul was in eighth grade when his catheter became infected, his lungs filled with fluid and he contracted pneumonia. His breathing became so labored that doctors had to connect him to a breathing machine. His kidneys failed completely and were removed, and he was forced to sleep sitting up so the fluid in his lungs wouldn’t choke him.

“I didn’t think he was going to live because he kept saying, ‘I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,'” his mother recalled.

After he recovered, the hemodialysis treatment began. Every three days, he sits for four hours in a chair, a needle in his arm, his blood coursing through a machine that cleans it out and then pumps it back into his body. If he goes for more than three days without treatment, he will become seriously ill from toxin buildup in his body, poisoning him from the inside.

His only hope is a kidney transplant.

‘If you’re rich, you can get a transplant’

Anne Paschke, a spokeswoman for the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, the private nonprofit that manages the nation’s organ transplant system, said immigration status does not affect eligibility to receive an organ transplant.

Ability to pay does, however.

“Besides a detailed medical and psycho-social evaluation,” Paschke said, a transplant center also will “evaluate the patient’s ability to take care of an organ if they get one.” What that means, she said, is “not only the ability to pay for the transplant, but for very expensive immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their life.”

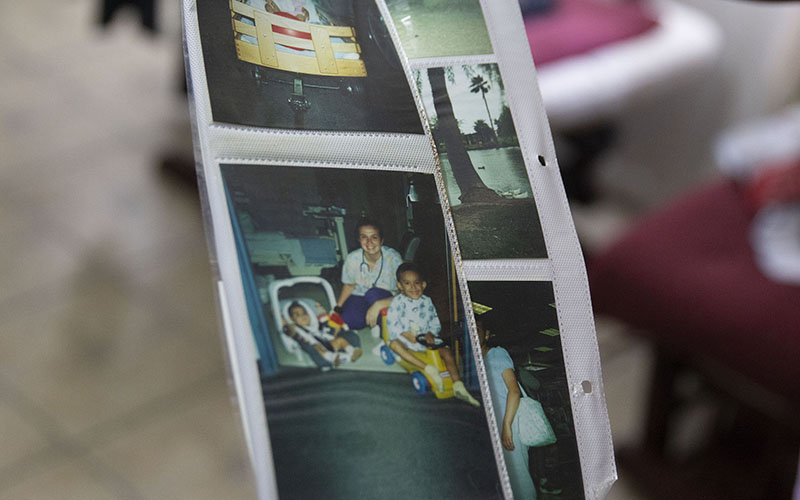

A family photo album shows Paul’s childhood, including the time he has spent in the hospital because of his failing kidneys. The problem was discovered when he was 2 and Paul’s kidneys were removed when he was in eighth grade. (Photo by Rebecca Spiess/Cronkite News)

UNOS operates the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, known as OPTN, under a contract with the federal government. Its job is to connect all professionals involved in the organ donation and transplant system. Phoenix Children’s Hospital, where Paul was treated for many years, follows OPTN and Medicare guidelines for evaluating patient eligibility, but every transplant center has the flexibility to impose other criteria based on a patient’s specific situation.

There are numerous factors considered for patients to even get on the national organ transplant list, and they are harder to navigate for lower-income patients like Paul. OPTN regulation requires that transplant centers pay a registration fee of $834 just to list a transplant candidate. Its educational guide also recommends that potential transplant patients get secondary insurance “to cover pharmacy costs and medical costs the primary insurance does not cover.”

But getting a straight answer on options available for DACA recipients can be a challenge. Experts from AHCCCS, countywide health-care providers, immigration law professors and advocates could not provide an answer. Only a customer service representative from the Arizona Department of Insurance was able to do that. She said that she had Googled it.

In theory, Paul’s family could buy health insurance outside the Affordable Care Act’s marketplace, at full price, or receive it through an employer. But paying full price for insurance is out of their reach, and although DACA gives Paul permission to work, his health issues make it difficult for him to hold a full-time job that might qualify him for benefits.

According to a 2013 report on DACA and health care from the National Immigration Law Center, DACA-eligible individuals remain “excluded from almost all affordable health insurance options” under the Affordable Care Act. The center also notes that DACA recipients often are treated as if they are undocumented in the insurance marketplace, “even though they are otherwise considered lawfully present and are eligible for a work permit and a Social Security number.”

Sonya Schwartz, a senior policy attorney at the center, said that DACA passed in 2012, two years before Obamacare fully took effect, and “for those two years, we were waiting for clarification, hoping for the best.”

“But then unfortunately the Obama administration, through a regulation about high-risk pools, created the DACA exclusion basically saying that, yes, there is a deferred action category, but it doesn’t include DACA recipients,” Schwartz said.

“That was a big blow to immigrants, and really, really disappointing. Not only can you not get the subsidies in the marketplace if you have DACA, but you can’t even purchase a plan at full price in the marketplace.”

Mo Goldman, an immigration attorney from Tucson, said DACA recipients often “shy away from getting medical insurance because it’s too costly” and avoid the vulnerability of exposing their status to get health insurance.

But without insurance, a transplant is out of reach. According to a 2017 report by Milliman Research, a human-resources consulting firm, the average cost of a kidney transplant, just for the 30 days before the transplant to the 180 days after the surgery, is a staggering $414,800. And costly medications may be needed for a lifetime.

“If you’re rich, you can get a transplant,” Paul said. “If you have papers, you can get a transplant. That’s the only way.”

A childhood stolen by illness

Paul was never able to really be a kid.

“When we were little, we’d say, ‘Oh, you know he can’t go swimming.’ Whenever we were at a party we’d say, ‘Oh, we have to go because you have to be connected to your machine,'” his cousin Katia recalled.

In school, Paul kept his illness from his friends, hiding his catheter and medical equipment from the other children.

Paul has been treated at Phoenix Children’s Hospital since he was a toddler. “They all know me and my mom,” he said. “We’ve been through the whole hospital, basically.” (Photo by Rebecca Spiess/Cronkite News).

“I grew up where you can call the ‘hood, so I didn’t really like sympathy from anybody,” he said. “I never really told a lot of friends.”

Baby pictures show family celebrations spent with nurses and doctors in the hospital.

“If I go right now to (Phoenix Children’s), they all know me and my mom,” Paul said. “We’ve been through the whole hospital, basically, up and down.”

At 19, Paul had another health crisis. He felt chest pains and called an ambulance, but he said they refused to transport him because his emergency insurance would not cover it. (According to the Emergency AHCCCS website, “determination of whether a transport is an emergency is not based on the call to the provider but upon the recipient’s medical condition at the time of transport.”)

His father drove him to the hospital, where a nurse told Paul that not enough oxygen was getting to his brain.

“The last thing I remember when I passed out was my ma, in the waiting room, talking to the nurses, signing papers. And then I collapsed,” he said.

He was intubated and fell into a stabilized coma.

It was the second time Paul’s mother thought she was witnessing her son’s last days. She knows the only solution for his health problems lies out of reach.

“I feel, more than anything, powerless,” she said.

For now, Paul is working again and continues to get dialysis. His new job, in construction, requires him to get up at 3 a.m. on most days to get there on time. His new colleagues have nicknamed him “El Chapo,” after the Mexican cartel kingpin Joaquín Guzmán, who, at 5 feet 5 inches, is almost as short as Paul.

But Paul says he doesn’t mind the jabs. He needs the money, and the clock is ticking.

Follow us on Twitter.