MOREHEAD CITY, N.C. – Ten weeks ago, Mary Rotchford’s home was destroyed and her life upended by a hurricane, and she and her family found themselves sleeping for weeks on cots in a converted senior center in this coastal city.

And yet she considered the experience a positive one.

“People only get together at funerals or weddings, but it was like we were all forced to stay in an enclosed area,” Rotchford said of the time spent in a shelter with about 30 other survivors of Hurricane Florence.

“We couldn’t go anywhere, we didn’t have to worry about food or anything like that, it was just a time to get together and meet your neighbors again,” she said. “When do you get to do that as adults, really?”

Rotchford’s comments were not uncommon among shelter residents here a month after Hurricane Florence slammed into the Carolinas, once the immediate shock had worn off and some semblance of routine had fallen into place.

The community banded together to help. Every day, people brought in food, toiletries, cleaning supplies, clothes, pillows and blankets – so much so that the shelter’s volunteers said they don’t know what to do with it all. Items that went unused were donated to Goodwill or the Salvation Army, where others in the community could access them.

One local man started a mobile laundry service, bringing a trailer equipped with washing machines and dryers to the shelter. Residents dropped their clothes off in the morning and got them back at the end of the day, clean and folded for free.

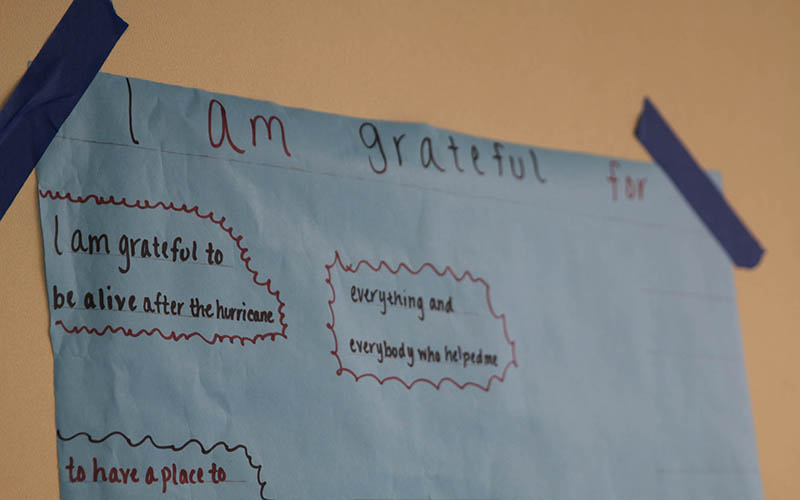

“We have all been blessed to be here, and I am a very grateful man for that,” said Willie S., a homeless man who asked that his last name not be used. He was living at the shelter with his Chihuahua, Lucky, but said the storm gave him a family he did not have before.

Maybe their attitudes came from a hurricane that helped put things in perspective.

Willie had resigned himself to dying in the storm, with Lucky, before they were plucked off the roof of a van by a Coast Guard helicopter.

Jean Currey, a Red Cross volunteer from Phoenix, said Hurricane Florence caused some of the worst devastation she has witnessed in 30 deployments to disaster areas over the past nine years.

“This one has really devastated the community because there wasn’t a lot of resources prior to the hurricane and a lot of the resources that were available have been adversely impacted by the hurricane,” she said. “A lot of the resources that you would generally find in an area are just not there.”

Currey, who spent close to a month helping Hurricane Florence victims in North Carolina this fall, has helped with floods, hurricanes and wildfires across the country. Whatever the cause, she said, the effect is still traumatic.

– Cronkite News video by Lillian Donahue

“As one of my clients told me a while back, ‘I took 30 years to build up what I have, and in 15 minutes, everything was gone,'” she said.

The National Weather Service was calling Hurricane Florence the “storm of a lifetime” for the Carolinas before it made landfall on Sept. 14 near Wilmington, N.C., about an hour south of Morehead City.

Peak winds as high as 140 mph had slowed to a sustained 80-90 mph by the time the hurricane hit, but the accompanying storm surge and massive amounts of rain – more than 2 feet fell over several days in Morehead City – brought flooding that caused much of the devastation.

More than 50 deaths have been linked to the storm, which caused an estimated $17 billion in damages in North Carolina alone, according to the governor’s office there. More than 32,300 households have been approved for assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which said this week that 500 families still were being housed in hotels or trailers. The last shelters closed Nov. 9, but assistance applications still are being accepted.

The Rotchfords were not originally planning to evacuate ahead of Florence. They said they had ridden out storms in the 10 years they had lived in their home without damage, and did not want to move their daughters, autistic adult twins, away from home.

But when they saw neighbors – whose families had lived on the land for more than 100 years and whose houses were lifted to avoid flood damage – begin to evacuate, the Rotchfords decided not to take any risks.

A government program that elevated homes in storm-prone areas stopped two houses shy of theirs, said Wade Rotchford, despite years of him trying to get his house in the program.

“My house did not flood during Floyd,” the last big hurricane to blow through, Wade said. Florence was different.

It flooded the Rotchford home, leaving the floor buckled and bubbled throughout. All of the flooring needs to be replaced, as well as much of the furniture. But the family is focusing on the positives.

“There’s a lot of memories in here for just the 10 years we’ve lived here,” Wade said as he picked through the home. “But it gave me an excuse, we’d been talking about how we needed to go through stuff and declutter, so now’s the best time to do it.”

Willie was staying at a motel when he missed a planned evacuation.

“I had to use the restroom … when I came back out, everybody was gone,” Willie said. “Me and my little dog, Lucky, were the last two left.”

With water rising in the room, Willie and Lucky climbed into a friend’s van parked outside. When Lucky climbed onto his lap at 4 a.m., “I put my hand on him, he was wet.”

“When I got up and looked, the water was already a foot deep in the van,” Willie said. An hour later, his feet were underwater and he called 911, but was told they would not be able to send a rescue boat to his location.

Willie said he had come to terms with the fact that he and Lucky were not going to make it, until a helicopter circled overhead and lowered two Coast Guardsmen to rescue him. When Willie said he was too weak to climb in rescue basket, one of the guardsmen took charge.

“He picked me up like a 5-pound sack of potatoes, gave me Lucky, and they took me into the helicopter,” he said.

Willie and Lucky were first taken to a pet-friendly shelter at a middle school, then moved to the Morehead City shelter when school was set to resume. Lucky was fostered at a Salvation Army volunteer’s home.

Another shelter resident, Alex Carias, also was homeless and living out of his truck with his dog, Gus.

“We sat out the hurricane in my truck in a parking lot,” Carias said. “It was a little scary, I was a little nervous thinking about what could happen to Gus.”

Gus ended up at the shelter, staying in an air-conditioned kennel in an on-site pet trailer where Carias, although he’s in a wheelchair, is able to visit every day.

Despite the bonds in this impromptu community, Currey, the Red Cross volunteer, said the lack of independence that comes from living in a shelter can be a problem.

“They want to be able to lay down on their own bed and not have anyone tell them what time to get up or what time to go to bed,” she said. “They want to be able to go into their kitchen and fix a meal without having to wait until somebody brings something in that they may have already had before and isn’t particularly their favorite.”

But Willie – who said all he had when had when the hurricane hit was “a pair of shorts, a pair of underwear, a dead cellphone and a Chihuahua” – has a different perspective.

He said his goal for his time at the shelter is to remind other survivors who have lost more than he did that “the property can be redone, refixed, replaced, but your life cannot.”

Connect with us on Facebook.