SAN FELIPE, Baja California – Just as the sun peeks over the horizon, casting an orange glow across the water, a group of fishermen takes off from docks at San Felipe. Their small, blue-and-white boats, known as pangas, bounce and rattle over the waves of Mexico’s Sea of Cortez.

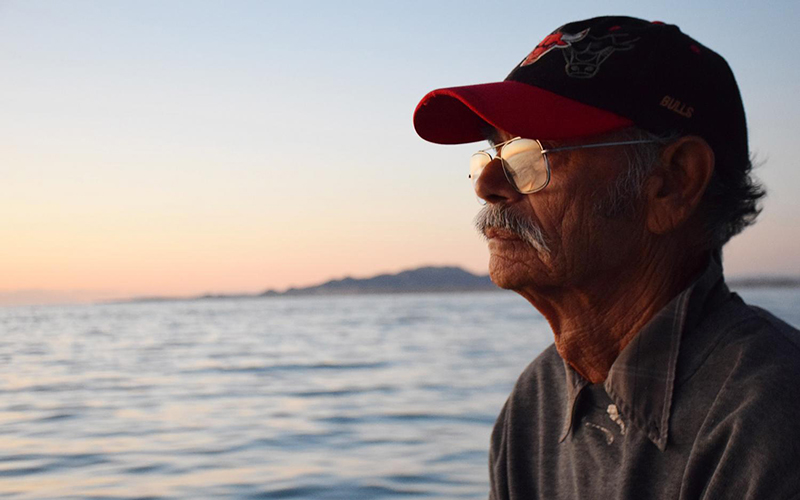

Ruben Orozco wears a Chicago Bulls ball cap and a gray, paint-stained sweatshirt as he heads out to sea.

“We’ve got to protect her,” he said of the vaquita marina, a small, shy porpoise found only in these waters. “Because she’s going extinct.”

The vaquitas last stand

• The struggle to save the world’s rarest marine mammal

• The struggle to save the world’s rarest marine mammal

• Saving the porpoise may depend on creating a legal market for totoaba

Orozco has spent his entire life on the water living next to the endangered vaquita. Now he’s among a group of fishermen working to remove illegal and abandoned fishing nets that threaten its existence.

Until a few years ago, Orozco and other San Felipe fishermen would would have been the ones casting nets.

Fishing has been the lifeblood of this 5,000-family village for a century. But gillnets were banned here four years ago in an effort to protect the vaquita marina. With fewer than 30 left, the little porpoise is on the verge of extinction.

Like many people who live around the northern Sea of Cortez, Orozco used to believe the vaquita was a myth.

“But not anymore,” he said.

The vaquita’s plight has brought scientists and activists from around the world to San Felipe, and with them has come more information about the porpoise, which grows up to 5 feet in length and weighs about 100 pounds.

Now that he has seen a vaquita, Orozco said, he’s invested in protecting it for future generations.

“For our grandchildren, our children, generations to come, so they will know (the vaquita),” he said. “Otherwise, they’ll never get the chance.”

At the same time, he said, fishermen need to be able to make a living.

Losing livelihoods

“We want to save the vaquita, too,” said Lorenzo Garcia, president of the largest fishermen’s federation in San Felipe. “But we don’t want to be left without work, without a living.”

He said fishing bans in the name of conservation have left the people of San Felipe without work. He said it’s destroying their town – shops are closing and children are showing up to school ragged and hungry.

The sun rises on the Sea of Cortez as fishermen prepare their boats for the day’s catch. Fishing has been the lifeblood of the 5,000-family village for a century. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

“It’s a huge social issue,” he said.

The problem is, fishermen’s gillnets are considered the leading threat to the vaquita.

In addition to trying to stop black market poaching, the Mexican government has outlawed all gillnets in the vaquita’s range. In return, it promised compensation for fishermen being put out of work.

But fishermen complain the compensation arrives late and sometimes not at all.

“San Felipe cannot live off the compensation only,” said Sunshine Rodriguez, an outspoken and controversial leader in San Felipe who says he won’t let fishermen take the blame if the vaquita disappears.

Although many conservationists believe even legal fishing nets endanger the vaquita, Rodriguez said there’s no proof – the mesh of their nets is too small to ensnare the little porpoise.

“So that’s where I come in as the perfect enemy because I won’t shut up and I won’t let them do whatever they’ve been pleased to,” he said.

He also said San Felipe fishermen are willing to use different gear, but the government hasn’t put forward an alternative that works.

“The only thing these people want is to have a decent living. They’re not criminals,” Rodriguez said.

But the ban has pushed some desperate fishermen into poaching, said Garcia of the fishermen’s federation.

“People have to find some way to make a living,” he said. “I don’t justify their fishing, either. But they have to find some way to feed themselves.”

When fishermen are struggling and know that catching totoaba pays, they’ll risk it. Especially when enforcement is almost non-existent.

Besides, Garcia said, banning fishing hasn’t helped the vaquita, whose numbers are still declining.

And, he said, there are other issues to consider – like the affects lack of water from the Colorado River have on the vaquita’s ecosystem, which was once brackish when it had freshwater inflow from the river, which is now heavily controlled.

Some researchers said the reduced flow of the Colorado has almost certainly affected the vaquita, but others argue that it’s a distraction from the real problem – gillnet fishing.

“In the meantime, we’re the ones paying the price,” Garcia said. “And the vaquita is being affected, too. And we have to care about the vaquita. But first, I have to think about my kids.”

Sustainable future

“This is not sustainable,” said Claudia Olimon, leader of a fishermen’s cooperative dedicated to using alternative gear and creating sustainable fisheries in the Sea of Cortez.

The fishermen in her cooperative have all given up their gillnets and are working with conservationists to remove illegal nets from the water. But that can’t go on forever.

Ruben Orozco, sitting in the front of his small boat, or panga, once thought the vaquita was a myth. He’s a believer now. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

“Fishing is going to exist sooner or later, so how? With which gear?” she asks, adding that long-term solutions must take fishermen’s perspectives into account.

Marcela Vasquez, an anthropologist and director of the University of Arizona’s Center for Latin American Studies who has studied fishing communities in the Sea of Cortez for years, said it’s a mistake to focus on single-species conservation.

“We should be looking at the ecosystem, to try to protect it. And part of this ecosystem is the human populations that live within it,” she said.

Putting more pressure on fishermen is counterproductive, she said.

“And for them, fishing is not just a source of money,” Vasquez said. “It is something that they love. It is an art.”

If there’s any hope for the vaquita, she says, it will come by creating legal, sustainable fisheries in communities that share the water with the little porpoise. Because the fishermen aren’t going anywhere.

Garcia agrees.

“And we’re going to fight for our ocean,” he said. “This is where we’ll stay, fighting for what’s ours.”

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.