The Sea Shepherd patrols the Sea of Cortez for illegal gillnets. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

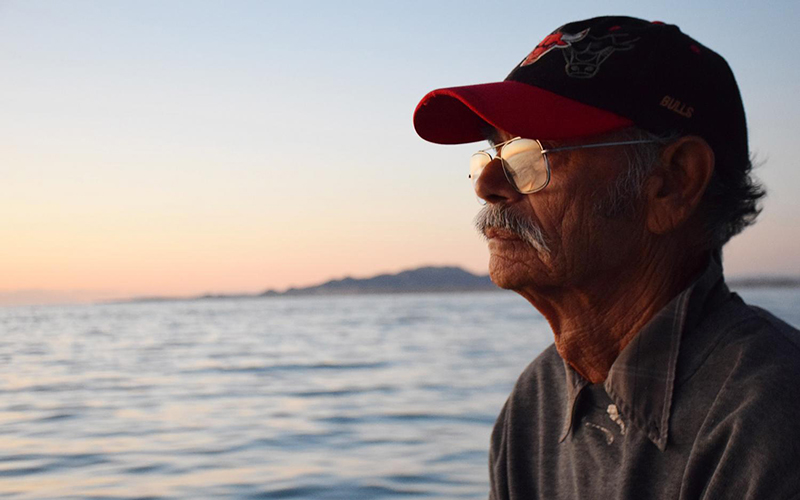

Sea Shepherd crew members Ivan Silva (left) and Jorge Amaya pilot the ship. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

The Sea Shepherd crew stores nets they have pulled from the ocean in a dirt lot on the outskirts of San Felipe, Baja California, until they can be sent away to be recycled. (Photo by Kendal Blust/KJZZ)

SAN FELIPE, Baja California – The activist sailors aboard Sea Shepherd’s big, white patrol ship in northern Mexico’s Sea of Cortez come from all over the world.

A recent crew included volunteers from Italy, France, Brazil, Mexico and the United States, among other places.

They’ve all joined the Los Angeles-based conservation society’s ship on the Sea of Cortez to help protect marine wildlife from cartel-backed poachers who use illegal fishing nets to hunt a huge, endangered fish called the totoaba. The totoaba’s swim bladder – an organ that controls buoyancy – is valuable on the black market in China.

But poachers’ gillnets also kill the world’s smallest and most endangered marine mammal – the vaquita marina.

“So we’ve got to do everything and anything we can to stop these poachers,” said Robert Peel, the ship’s captain. “Because their quest for easy money is going to exterminate a very nice little creature called the vaquita.”

The vaquita marina, or little sea cow, only lives in the uppermost part of the Sea of Cortez.

The little porpoise, sometimes called the panda of the sea because of the black markings around its eyes and mouth, has been critically endangered for decades. And its population has plunged in recent years, despite efforts to save it. Scientists estimated that there were nearly 600 vaquitas in 1997. By 2016, that dropped to 30. Now it could be as few as 15, or 12.

Sea Shepherd crew members pull an illegal gillnet out of the ocean. (Photo courtesy of Sea Shepherd)

“And the number of vaquitas have been going down and down and down every year. So yeah, it’s really, really sad,” said Jean Paul Geoffroy, campaign director for Sea Shepherd operations in the Sea of Cortez.

In fact, the vaquita’s numbers have dipped so low, some say it might not make it through another totoaba fishing season, when the large fish is spawning in the same part of the sea where the vaquita lives, from about November to May.

Totoaba gillnets are already illegal in this part of the Sea of Cortez. And hunting totoaba has been banned since 1975, when the 200-pound fish became critically endangered because of overfishing.

But that hasn’t stopped poachers.

“There’s a lot of demand in Asia for these species of totoaba,” said Alfonso Blancafort, Baja California state representative for the Mexican agency charged with protecting the environment (SEMARNAT).

The totoaba swim bladder – or buche – is called the “cocaine of the sea” it’s so lucrative on the black market in China, sometimes worth as much as $80,000 per kilo.

“As you can imagine, there is a lot of crime involved in these activities,” Blancafort said.

Totoaba bladders are trafficked by the same cartels that smuggle drugs, Sea Shepherd’s Geoffroy said.

“We are talking about a lot of money. And we know, too, they’re using the same ways to take it out of the country as they use for the drugs,” he said. “So, it’s the same people.”

Walls of death

Geoffroy drives out to a big dirt lot where Sea Shepherd stores the illegal nets they haul out of the ocean. They find hundreds every year.

Tangled, grimy piles of net spill out of disintegrating plastic bags heaped nearly 8-feet high in places. The nets will be cleaned and sent away to be recycled, so they can’t make their way back into the ocean, Geoffroy said.

He calls the nets walls of death.

A totoaba gets caught in a gillnet. (Photo courtesy of Sea Shepherd)

“It’s kind of murky, you don’t have visibility. And you’re just swimming around and hit a wall and die. That’s it,” he said.

And because adult totoaba, which can be over 6-feet long and weigh as much as 200 pounds, are similar in size to the vaquita, the nets easily entangle and drown the small porpoise.

“Because they breathe air like we do. It’s a marine mammal. They need air to breathe. They need to go up and breathe,” Geoffroy said.

He said fighting poachers is an uphill battle. For every net Sea Shepherd pulls, another goes back in its place. A big part of the problem is lack of enforcement, he said.

Related stories:

• Vaquita’s last stand: Fishermen want to help, but need to feed their families, too

• Vaquita’s last stand: Fishermen want to help, but need to feed their families, too

• Vaquita’s last stand: Saving the porpoise may depend on creating a legal market for totoaba

Mexico has made strides against poaching – it’s created a refuge area, banned fishing nets and sent the military in to patrol for totoaba traffickers.

In September, Baja California state police detained a suspected totoaba smuggler with connections to the Sinaloa cartel. But then he was let go, rearrested and ultimately released on bail.

Brooke Bessesen is a wildlife researcher who wrote a book on the vaquita’s plight. She said it’s clear authorities are reluctant to prosecute totoaba smugglers.

She said there are “government officials who are either potentially taking money and/or fearful, spooked, and unwilling to speak up.”

But everyone knows that poachers are still out there, she said, casting nets in the dead of night, sometimes even in the middle of the day.

And in the meantime, the vaquita edges closer to extinction.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.