Annita Lucchesi speaks about the report she co-authored, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, as Sens. Lisa Murkowksi, R-Alaska (left) and Maria Cantwell, D-Washington, look on. (Photo by Lillian Donahue/Cronkite News)

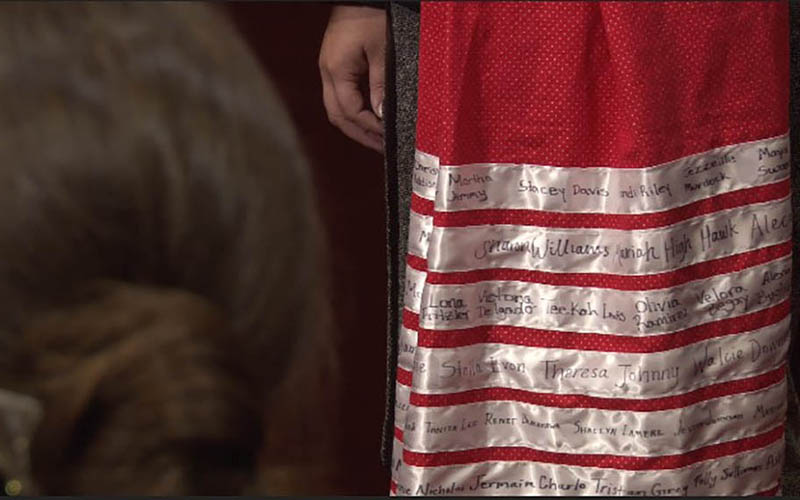

Abigail Echo-Hawk, co-author of the report, holds a skirt decorated with the names of some of the Native American women who have been killed or are missing in urban areas with little notice from authorities. (Photo by Lillian Donahue/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – On Nov. 14, 1992, a Native American woman was found murdered in Tucson, and 26 years later her name is still not known.

That’s just one example of the lack of solid data that has led to the underreporting of hundreds of deaths and thousands of missing persons cases for Native American women and girls living in urban areas, a new report says.

The report by the Urban Indian Health Institute pointed to the fact, for example, that there were 5,712 cases of missing indigenous women and girls to the National Crime Information Center in 2016, but only 116 were logged in the Justice Department’s missing persons database.

“You will never solve a problem you won’t admit you have, that you don’t have data on, that you don’t have the ability to analyze exactly what is happening,” said Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, D-North Dakota, co-sponsor of a bill that would require better federal collection of such crime data in urban areas.

The data was collected from police departments in 71 cities and 29 states through public information requests, a process that turned up 506 cases of Native women or girls who were murdered or missing or whose case status was unknown. The report began by saying that number was likely “an undercount.”

While rates of violence on reservations have been found to be as high as 10 times the national average, the report said, no research had been done in the area of indigenous women in cities, even though “71 percent of American Indians and Alaska natives live in urban areas.”

“And because we live in these cities there is the assumption that the same resources, the same police that every one of you would call would answer your call in the same way they answer mine,” said Abigail Echo-Hawk, who co-authored the report with Annita Lucchesi. “And I’m here to tell you, and our report is here to tell you, that is wrong.”

The difficulty of getting access to information was spotlighted in the report: Of the 72 law enforcement agencies contacted, 40 provided some data, 14 did not provide data and 18 still had pending public records request as of Oct. 15. The institute said three Freedom of Information Act requests filed with the Los Angeles Police Department did not result in any data for the report.

“They (LAPD) had a backlog of thousands of requests that three staff members were responsible for filling, and many were not answered” as the institute’s first request was, the report said. “Or were rerouted to the wrong agency (as UIHI’s second request was). An entire year later, the agency expected UIHI to file a third request and ‘get back in line.'”

Although the oldest case found in the report was from 1943, less than half the agencies contacted were able to provide data from before 2000 and 77 percent did not provide data from before 1990.

Nine cities, or 13 percent of the total, said they were not able to search for American Indian or Native American victims in their databases. Police in Fargo, North Dakota, told the report’s authors that “sometimes the information (on a victim’s race) would not be asked and our record system defaults to white.”

“One of the areas that really needs to change in Arizona and in other states is that there is rampant misclassification of race and ethnicity,” Echo-Hawk said. “People aren’t asking the race and ethnicity of those who are going missing and murdered, and if they’re asking them, they’re not putting them in the databases.”

One page of the report said that “several police departments provided UIHI with data that included both American Indians and Indian-Americans with visibly Indian American surnames (e.g. Singh).”

Savanna’s Act, named for a murdered Native American woman, would strengthen federal efforts to collect data on missing or murdered Native Americans. The bill was passed unanimously Wednesday by the Senate Indian Affairs Committee.

Arizona cities examined in the report were Flagstaff, Phoenix, Tempe and Tucson. Tucson reported 30 murders and one missing person case. Flagstaff had seven murders, Tempe had two murders and one case whose status is unknown while Phoenix had six murders and eight missing person cases.

“The community has a stake in safety there in the city and knowing what kind of violent crime is occurring and who are the victims … it’s imperative that the police provide that information,” Lucchesi said.

-Video by Lillian Donahue

Follow us on Twitter.