A proposed residential development s in Yorba Linda, California, would be built near an area that sustained heavy fire damaged during the 2008 Freeway Complex Fire. (Photo courtesy of James Bernal/KPCC)

YORBA LINDA, Calif. – It’s a real-estate paradox: The most desirable places to live also are among the most susceptible to wildfires.

Mansions in the Santa Monica Mountains, tiny cabins tucked into the Angeles National Forest and homes at the edges of subdivisions all are beautiful because they’re surrounded by undeveloped land. But that land is a tinderbox.

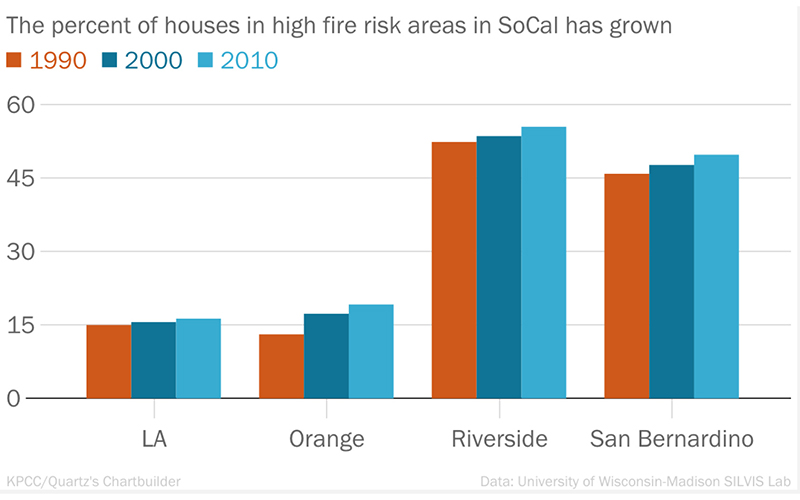

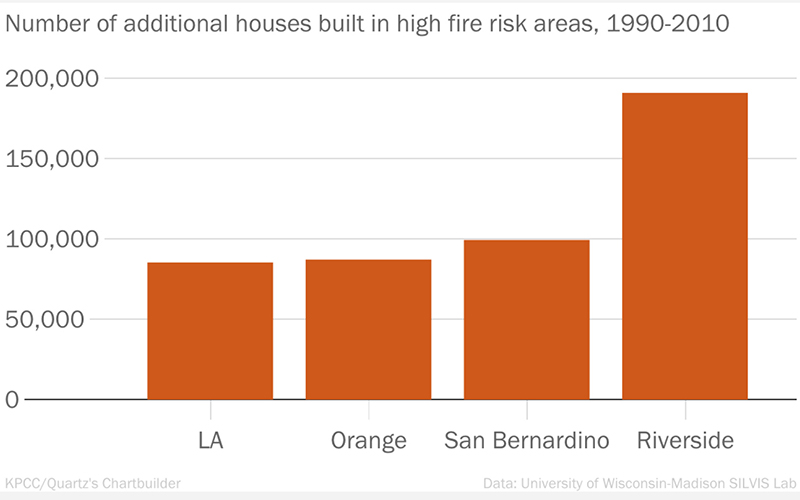

Every year in California, there seems to be a bigger, crazier, more destructive wildfire. But every year, new houses go up in their path. And it’s not just some houses, but thousands – more than 85,000 new houses in high fire risk areas in Los Angeles County alone, from 1990 to 2010.

Shouldn’t we know better by now? Why do we keep building houses in places that are likely to burn? I’ve reported countless wildfires over the years and this question continues to come up.

To answer it, I examined a housing development proposed for an undeveloped swath of land in Orange County north of Yorba Linda. Esperanza Hills is a fancy development: 340 multimillion-dollar homes on a gated, dead-end street.

It definitely fits the definition of high-risk – 10 years ago, a wildfire completely scorched the land Esperanza Hills would be built on. And Cal Fire – the state’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection – calls the entire site a “very high fire hazard severity zone,” a wonky term for an area that’s likely to burn again in the next 30 to 50 years.

That matters because fire ecologists say where – and not how – you build your house is the most important factor in determining whether it will burn.

“There are many cases where you can do everything right, but if you’re in a very risky location, your house can burn down,” said fire ecologist Alexandra Syphard, who has been studying wildfires for 20 years.

Building with modern, fire-resistant materials, clearing 100 feet or more of brush from around your house — those things can help, but if you put your house in a fire-prone place, Syphard says, such measures are mere Band-Aids.

‘The most dangerous site … you could pick’

On Nov. 15, 2008, a small brush fire started near California State Route 91, which lies in a corridor for Santa Ana winds. The fire raced west, connected with another blaze and torched the entire Esperanza Hills site before moving south into Yorba Linda and burning 381 homes. The Freeway Complex Fire was one of the most destructive in Orange County history.

The evacuation was chaotic, recalls Ed Schumann, who was among those who lost their homes. Streets were gridlocked. Kids were running down the sidewalks with their pets. At one point, a teenage boy got out of his car to direct traffic because no one else was doing it.

Melanie Schlotterbeck, a consultant for nonprofit Hills for Everyone, shows the history of fires in the region. (Photo courtesy of James Bernal/KPCC)

To Schumann and other Yorba Linda residents, the idea of adding 340 houses and residents and vehicles to that mess is frightening.

“Evacuating that many more people with the same infrastructure, it’s a scary thought,” he said.

It’s why Kevin Johnson, a lawyer for one of the environmental groups that sued over the Esperanza Hills project, delaying it for years, calls the location “probably the most dangerous site in Southern California you could pick to put 340 new families into.”

Meet the developer

So, why would anyone want to build in such a risky place? I reached out to the developer behind the project, Douglas Wymore.

He has his reasons. First, he believes he can build these houses, on this site, safely.

“I disagree with somebody that just comes in and says, ‘Oh, anytime that you put something next to an open-space area that’s a very high fire (hazard) zone, you can’t protect it,'” he said. “I think the bottom line is you can mitigate it, you can protect it.”

And Wymore is doing a lot to protect it. All the houses will be “hardened” – in other words, built using fire-resistant materials as required by state building code, including sprinklers in the attic.

He’s planning at least 170 feet of defensible space around the homes. There will be two on-site water tanks for firefighting. And two entrances, one for emergencies, one for everyday use (local residents say this is insufficient, and point to the multiple tight turns on the main entrance, but Wymore is doing what is required under the county’s fire standards).

Second, by building modern, fire-resistant homes in the path of a wildfire, Wymore believes he is protecting everyone else in the area whose houses may not be up to the latest building codes. His project, he contends, will act as a fire buffer for older, more flammable homes.

And third, he says, people want to live here.

“The bottom line is, there’s a demand for people that want to live in those areas for obvious reasons,” Wymore said. “And so if you’re going to take on the task of satisfying that demand and building a project, I think you have a responsibility to make sure you do what’s necessary to make your development safe.”

Follow the money

That’s why the developer wants to build. But given the obvious risks, why would the Orange County Board of Supervisors approve this project?

Well, to start, it will generate $8.25 million a year in property taxes. And since voters passed Proposition 13 in California in 1978, which limited how much property tax bills can go up each year, cities and counties haven’t seen their tax revenue increase as housing values rise.

“Prop 13 handcuffs local jurisdictions in finding additional revenue,” said Howard Penn, executive director of the Planning and Conservation League. “They can raise sales tax or build more homes. There’s not a lot of ways to get more revenue.”

It’s also worth mentioning that since 2011, Wymore has donated nearly $50,000 to the re-election campaigns of several members of the Orange County Board of Supervisors, none of whom would talk to me for this story.

Wymore was frank about why: “If you put political donations in, whether those people agree with you or don’t agree with you, they will at least give you an opportunity to sit down with them and listen. Which maybe they would and maybe they wouldn’t do otherwise.”

Although none of the county supervisors wanted to talk, you can get a pretty good sense of why most of them support it from things they said at previous public meetings about the development. One big reason is the classic private-property rights argument: Wymore owns the land, and he should be able to develop it as he sees fit.

“I don’t have any reason to now deprive someone of the right to use their property,” Chairman Andrew Do said at a May 2017 meeting.

Another big reason? Fire officials had given Esperanza Hills the green light.

“If the fire department is satisfied, I’m not inclined to argue with them. I’m not a fireman,” Supervisor Shawn Nelson said.

Deputy fire marshal Timothy Kerbrat of the Orange County Fire Authority said the preliminary plans for Esperanza Hills met all the state and local requirements for building in a high-risk area.

“Do they have access, do they have water, do they have defensible space, do they have hardened structures that they can protect? Are all those things occuring? And in the Esperanza project, that’s the things that I’m seeing. That it’s occurring,” he said.

Although the supervisors approved the project in May 2017, an Orange County environmental group sued and a judge overturned the approval, which is why Esperanza Hills was back in front of supervisors again on Sept. 25. And, despite continued opposition from some homeowners, the board approved the project 4-1 – prompting one homeowner to shout, “See you in court!”

Taxpayers on the hook

There’s another factor here: The Orange County Fire Authority will get just more than $1 million a year in revenue from the Esperanza Hills project.

And if a large wildfire breaks out, the agency likely won’t have to spend much of its own money to protect this neighborhood. That’s because state and federal agencies largely reimburse local fire departments for the costs of firefighting.

Back in 2008, for example, the Orange County Fire Authority spent $2.3 million fighting the Freeway Complex Fire, but 94 percent of those costs were reimbursed.

“The irony is that we, as taxpayers, are paying for the protection of homes that are built in high-risk areas,” said Kimiko Barrett, a researcher at the Montana-based think tank Headwaters Economics.

You read that right: When a big fire breaks out and threatens houses built in risky places, you and I are the ones picking up the bill.

Kerbrat, the deputy fire marshal, staunchly denies that money or firefighting costs play any role in approving developments.

“I’ve never heard firefighters, or a fire agency, talk in that manner,” he said. “It’s not in our thought process. We don’t think of this as a business, for profit.”

Barrett, however, calls the situation a moral hazard.

“The consequences actually aren’t borne by the people who are approving these developments,” she said.

And it’s not just Barrett with this assessment: The Office of Inspector General agreed in a 2006 report.

“If state and local agencies became more financially responsible for (wildland-urban interface) protection, it would likely encourage these agencies to more actively implement land use regulations that minimize risk to people and structures from wildfire,” they wrote.

But until this case of misaligned incentives changes, Barrett says, we’re going to keep building in risky areas. Nearly 1 million new houses in California could be built in these areas before 2050.

Perhaps that’s why Wymore chose to call his project Esperanza – the word means “hope” in Spanish.

This story is part of an Elemental series “Fire in the Neighborhood” about fire danger in cities and surrounding areas.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.