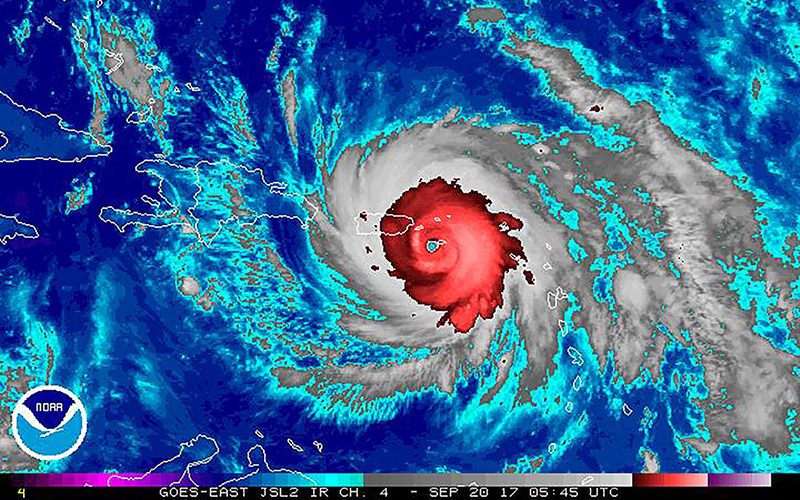

A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellite of Hurricane Maria as it reached its most powerful point on Sept. 20, 2017, just as it reached Puerto Rico. (Photo courtesy the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Hispanic Federation President Jose Calderon said that in its response to Hurricane Maria a year ago, the Federal Emergency Management Agency “failed miserably, we need to call it what it is.” (Photo by Ian Solomon/Cronkite News)

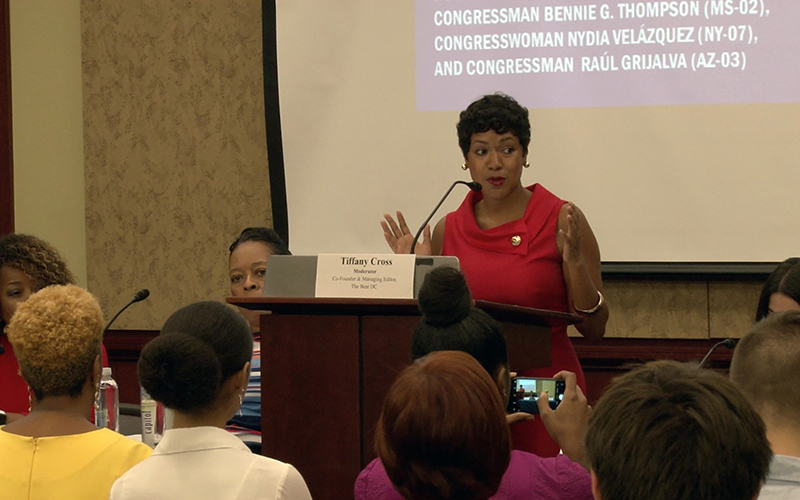

Tiffany Cross moderated the Capitol Hill panel on the government’s response a year ago to Hurricane Maria, saying it was the biggest Capitol Hill panel of experts to meet on the hurricane since it hit. (Photo by Ian Solomon/Cronkite News)

Maria Torres, husband Jose Cruz and daughter, Gladys Cruz-Torres, from left, sit in another daughter’s home last fall after their home in Puerto Rico was damaged by Hurricane Maria. (Photo by Lysandra Marquez/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – One year after Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico, Arizona State University Professor Maria Cruz-Torres said her parents on the island are still struggling to complete repairs to their house after getting “no help from FEMA at all.”

Her complaints were echoed at a Capitol Hill conference Thursday where experts called for a 9/11 Commission-style investigation into the government’s response to the storm that left an estimated 3,000 people dead, making it the deadliest American natural disaster in a century.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency “failed miserably, we need to call it what it is,” said Jose Calderon, president of the Hispanic Federation, at the event that one participant called “the largest Capitol Hill gathering of experts” since the storm struck Puerto Rico.

Calderon was flanked on the panel by philanthropists whose companies did humanitarian work in Puerto Rico after the hurricane. Kellie Bentz, head of global disaster response and relief at Airbnb, said efforts to house both victims and humanitarian-aid workers was slowed down by the process involved in FEMA’s contractor system.

Jeanette Morelan, communications and marketing manager for World Central Kitchen, said that Puerto Rico was already importing about 85 percent of its food before Hurricane Maria. Since the storm, that has shot up to 98 percent, she said.

Hurricane Maria hit the island just two weeks after another powerful storm, Hurricane Irma, passed Puerto Rico as it swept through the Caribbean. Both storms reached Category 5 levels of intensity at different points in their development.

In an after-action report, FEMA conceded that its response was lacking in many respects.

“FEMA leadership acknowledged that the agency could have better anticipated that the severity of hurricanes Irma and Maria would cause long-term, significant damage to the territories’ infrastructure,” the report said.

Arizona State University Professor Maria Cruz-Torres said her elderly parents are still struggling to repair their house in Puerto Rico after it was damaged in Hurricane Maria last year. (Photo courtesy Mariz Cruz-Torres)

“Leadership also recognized that emergency managers at all levels could have better leveraged existing information to proactively plan for and address such challenges, both before and immediately after the hurricanes,” it said.

Calderon said Thursday that the current problems on the island are largely a “man-made crisis thanks to what’s happened here in Washington, D.C.” and the government’s response. But the “real environmental crisis” the island faces is in the future, he said, as climate change is likely to produce hurricanes that will only increase in intensity.

Calderon added that the hurricane had raised Puerto Rico’s profile on the national stage, only because before the storm, “Senators and congressional members they just have no clue whatsoever … that Puerto Rico even existed, let alone obviously that these were American citizens.”

Cruz-Torres, a professor in ASU’s School of Transborder Studies, said that anger on the island is directed at both the federal and local governments.

She has had to pay for repairs to her elderly parents’ front porch in Yabucoa, a municipality to the Southeast of San Juan. Her father, 93, and mother, 82, did not have their electricity restored until the second week of May, and one year later the house is about 80 percent repaired, she said.

Cruz-Torres added those in the coastal areas, fishermen in particular, were among the hardest hit because of the gear and boats they lost. Despite resentment toward the government response, Cruz-Torres said those on the island have shown great resilience in the face of adversity.

“It shows people can help each other if they want to,” she said.

Follow us on Twitter.