TACOMA, Wash. – With a thunderous crack of the bat, Andrew Aplin jolted the baseball high into the clear cool Tacoma night sky.

But the ball’s flight peaked in right field and plummeted back to earth, caught well short of the warning track for the final out of the night, sealing an extra-inning loss for Aplin’s Tacoma Rainiers. The former Arizona State star turned back toward the home dugout, pulling off his batting gloves as the visiting Salt Lake Bees poured onto the field, victoriously high-fiving behind him.

For Aplin, minor league game No. 673 was in the books.

Yet even after more than five years in the minors, his first MLB call-up has remained elusive. The center fielder is still waiting on that first big league at-bat.

It’s been a while since “MLB U” has put a player in the big leagues.

Arizona State’s baseball program, worthy of its nickname as a historic pipeline to the pros, has produced 108 MLB players in its history. But it’s been almost two years since Trevor Williams became the latest former Sun Devil to make his debut. If no new ASU product debuts this season, it will be the first time since 2000-01 that the school didn’t have an alumnus make a debut in back-to-back seasons.

If that streak is to end, it will likely be a player out of Tacoma, where Aplin and ex-ASU reliever Darin Gillies (also yet to make his MLB debut) play for the Seattle Mariners’ Triple-A affiliate, the Rainiers, a club managed by Pat Listach, another former Sun Devil who played at the school in the late ‘80s.

“He had a good career there, too,” Aplin pointed out when asked about his manager. “They had some good teams there when he was there. We like giving all the guys a hard time.”

Seth Mejias-Brean, one of two Arizona Wildcats in the Rainiers clubhouse, is a common target. Aplin says he has a couple favorite lines when smack-talking about the rivalry. “But I don’t think you’re allowed to write them,” he laughed.

Those college days seem far away now, though.

Combined, Aplin and Gillies have played more 800 minor league games across 11 seasons. Drew Maggi, an infielder in the Cleveland Indians organization, is the only former Sun Devil to have played in more minor league games without a big league appearance.

Conquering minor league baseball, they’ve learned, is a grueling task. Their toils have taught them many lessons.

“You don’t realize how much of a grind minor leagues is until you actually get here,” Aplin said, exhaustion in his voice as he recounts his half-decade long minor league career. “(You don’t) realize how many steps there is to take and how many good players there are that you have to beat out to get to where you want to go.”

Added Gillies: “Ever since the day we started playing this game, the end result (was) we always saw ourselves playing in the major leagues. It takes some maturity to take a step back and realize there is a process to that and there are steps you have to go through in order to achieve that dream.”

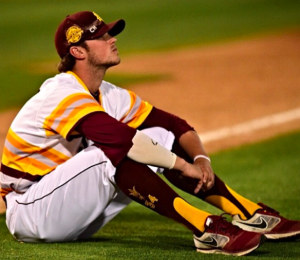

Andrew Aplin: peaks and valleys

Beyond the seats down the right field line at Tacoma’s Cheney Stadium, Mount Rainier juts up from the horizon line, its peak still capped in snow even in the middle of July.

Andrew Aplin played at ASU from 2010-12 before being drafted by the Astros in the 5th round. He is now with the Triple-A Tacoma Rainiers (Photo: Courtesy Andrew Aplin via Instagram)

It’s a picturesque backdrop. No mountain summit on the country’s mainland rises higher above its surroundings. It’s quite literally the highest peak in the 48 states. And the treacherous 9,000 foot, nine-mile climb to the top is an all too perfect metaphor for the difficult road through minor league baseball.

Andrew Aplin has traversed plenty of peaks and valleys during his journey. The self-described “die-hard Sun Devil” can’t help but to smile when thinking back to his collegiate career: He was part of the 2010 College World Series team, the last ASU squad to reach Omaha. He was an all-conference honorable mention selection in 2012, the same summer the Houston Astros, in the midst of baseball’s savviest rebuild, drafted him in the fifth round.

But before all that, there was a moment just months into his first semester on campus they helped lay the groundwork for the success that was to come.

Aplin was lured to Tempe from his Northern California hometown, Vallejo, by legendary Sun Devil coach Pat Murphy. But in November 2009, just months into Aplin’s first semester on campus, Murphy resigned amid controversial allegations of NCAA rules violations.

It was less a reality check and more a bomb of instability that threatened to derail his career before it began.

But former assistant coach Tim Esmay — who was let go by Murphy in the summer before Aplin arrived — was brought back as interim coach and Aplin flourished. He hit .337 in over 40 games. In the Super Regionals, he scored a game-tying run in the bottom of the ninth as part of a come-from-behind walk-off win. The next night, the Sun Devils clinched a trip to Omaha.

“Being such a young kid. Right out of high school, battling and dealing with adversity, losing the coaching staff you had committed to, just being able to come back from that and get to the College World Series, the pressure of all those games, the most pressure I’ve been in for sure,” he said. “Being that young and being able to get to do that at such a young age helped build the process of being a young player.”

Once in the pros, he rose quick, ascending to Triple-A in just his second full season. He participated in big league spring training in 2015 and was added to Houston’s 40-man roster later in the summer. His minor league club, the Fresno Grizzlies, won the Triple-A National Championship. An MLB call-up looked inevitable.

“I flew through the system,” Aplin remembered.

Then, he plateaued.

He went to spring training with the Astros again in 2016 but didn’t make the big league opening day roster. Then, he hit a woeful .223 in Triple-A that summer, the lowest batting average of his minor league career. Meanwhile, the Astros were getting good.

A once clear path to the majors was suddenly muddied. It was the first true setback he’d ever experienced.

“It’s tough, especially not failing before and then failing at one of the higher levels, on the 40-man,” Aplin said. “You just try to battle through it. It takes a toll on you, but it makes you a better person and a better player.”

By midway through the next summer, the Astros traded him to the Mariners for a “player to be named later” and cash considerations. He finished out last year in Tacoma before being assigned to Double-A Arkansas at the start of this season.

The decline was maddening.

“You feel almost defeated at first, the initial reaction, just because you’re going backwards,” he said of going back to Double-A. “You never see yourself going backwards.”

Aplin reached the point from which many minor leaguers never recover. To come that close to the bigs, only to get traded and demoted can be a demoralizing turn of events. He admits he used to keep a keen eye on Houston’s MLB roster, anxiously waiting his turn for the call up.

“The first couple years I was with the Astros, I was on the 40-man, so you’re always looking at what’s going on,” he said. “I could be the first guy up. Then you get locked into that and forget about just going out there and playing baseball, playing hard.

Two years later, the 27-year-old Aplin was beginning the season two tiers below the bigs, where he was more than three years older than the average Double-A player, according to Baseball Reference.

“After the initial reaction, you say, ‘OK,’ and step back and look yourself in the mirror and realize, ‘I need to do this. Go there and work on something and take something out of it,'” he said.

He’s started climbing again this season.

Darin Gillies: day by day

Hours before Aplin’s game-ending flyout, Darin Gillies takes a seat at a picnic table, propping one leg up on his side of the bench, situated to the side of Cheney Stadium’s long outdoor concourse.

It’s about 90 minutes before first pitch on this late Saturday afternoon and a cool Northwest breeze has kicked up, catching the long locks of the former Sun Devils’ flowing head of hair, forcing him to pull loose strands from his face and back behind his forehead. It is his only distraction as he dissects his burgeoning career.

Darin Gillies was a part of the first ASU team to play at Phoenix Municipal Stadium in 2015. (Photo courtesy Darin Gillies via Instagram)

To this point, Gillies’ career has mirrored Aplin’s early years. He’s progressed in a hurry, reaching Triple-A by his third full season. According to Baseball Reference, the 25-year-old is more than a year-and-a-half younger than the average pitcher at this level.

It hasn’t kept him from learning the struggles of the minor leagues. He speaks with purpose as he strings sentence after sentence, reciting the array of philosophies he’s picked up along the way.

“Work as hard as I could.”

“Put my head down and listen.”

“Try to be the best version of myself.”

“There’s a lot of work left to be done.”

There is one lesson though that stands out among the rest.

“When I got drafted, you see a little timetable to your future, but at the same time, once you get in it, you realize it’s all about taking it day by day,” he said. “I can’t stress that enough and the fact of how much that’s helped me.

“I think that’s really helped me progress through the minor leagues as fast as I have, is that experience of being able to break it down … and not look too far into the future. Try to be where you are for that day and try to make the most out of it.”

Gillies used to be a starting pitcher. It was his predominant role during his first three years at ASU from 2012-14 under Esmay. He never got comfortable in the rotation though.

“As a starter, the pit I fell into was I had too much time to think,” he said. “I struggled with all the free time. My mind would wander a little bit.”

For those first three years, his ERA hovered around 5. After his junior year, he went undrafted. Looking back, he says it’s the best thing to have ever happened in his career.

“It allowed some humility to come in and just realize the fact that I can’t take this game for granted,” he says. “I played my whole senior year not knowing if I was going to play baseball the next year.”

There were other uncertainties entering his senior year, too.

Unlike Aplin, Gillies’ bouts with adversity struck at a much earlier stage. After a string of early NCAA Tournament exits, Esmay was replaced as coach by Tracy Smith. The Sun Devils also changed venues, moving from historic Packard Stadium into the refurbished Phoenix Municipal Stadium.

Weeks into the season, Gillies was moved to the bullpen for good to aide a scuffling middle relief staff. He became a versatile swingman, capable of pitching multiple innings in the middle of a game to bridge the gap to the back end of the bullpen.

Finally, things began to click. The right-hander registered a career-best 3.83 ERA in 28 appearances, punching out 58 batters in just 49 ⅓ innings pitched. It caught the attention of big league scouts and the Mariners selected him in the 10th round of the draft.

“The game of baseball is full of adversity,” he said. “That deal, going through the coaching change and the field change and everything, that set the tone for what I was going to go through here in the minor leagues. There’s a lot of that: changing teams, changing locker rooms. Guys come in and out and have different feels at different times.”

At first, the Mariners experimented with him as a starter again (he started six games in short-season A-ball during 2015). Before 2016, he asked the organization to give him a permanent role. He went back to middle-to-long relief.

“The thing I’ve really enjoyed about the bullpen is that when that phone rings and they call your name and you’ve got to get up, for the most part it’s either going to be really quick or it’s going to be in a pressure situation,” he said. “So there’s a demand for strikes and a demand for outs right away. There’s not really so much time to let bad thoughts creep into your mind.”

Gillies opened this season in Double-A but was called up after just seven games. Listach thinks the ASU product is “on his way” to the bigs.

“If he develops the consistency with the slider and keeps the fastball right in at 93-95, he’ll have some success at the big league level,” Listich said.

Asked if he feels more pressure now that he’s on the doorstep of the MLB, Gillies responds with another adage of wisdom.

“Pressure, in my opinion, is something you put on yourself,” he said.

“When I get thrown in there, it’s me trying to know myself as a pitcher and trying to know what I do well. Regardless of what the hitters’ strengths are or what they’re doing, I’m going to come up with my best stuff and see what happens.”

The final step

Aplin and Gillies have positioned themselves well.

Aplin has refined his swing and approach at the plate this year, a change he was motivated to make after his struggles the last two years. He’s always had plate discipline (Aplin has never struck out 100 times in a season) and superstar defensive abilities (the Rainiers broadcast team has nicknamed him the “human highlight reel”) but now is hitting the ball to all parts of the park to the tune of a career-best .295 Triple-A batting average this year.

His career arc reads more like a EKG — going up and down and up and down. But he’s finally on the ascent again.

“It’s a breath of fresh air,” he said. “It’s a lot more fun when you’re playing good.”

Gillies has had a bumpy introduction to Triple-A, currently owning a 5.44 ERA in 26 appearances, but is still one of the Mariner’s top 30 prospects, according to MLB Pipeline.

It’s impossible to predict if he’ll hit the same ceiling Aplin has, or how he’ll handle a flatline in his career arc. These are the psychological traps that Triple-A can create, when the peak of the sport lies just an hour to north. Aplin and Gillies hope to one day make that trek, to play on the MLB stage and add to their alma mater’s baseball legacy.

They’re both so close, yet facing the tallest hurdle of them all.

“You can’t play GM,” Aplin said, speaking from experience. “Nobody knows what’s going on. I mean, half the time I don’t know if they know what is going on. You just keep your head down and keep going and try to play as hard as you can.”

Adds Gillies: “Anybody that answers that question and says they don’t pay attention to that stuff is lying. But it’s one of those things, if you have something to revert back to — which for me is taking it day by day — and that process and the sense that if I do everything in my power to make myself successful, at the end of the day I’m either going to end up in the major leagues or not end up in the major leagues.

“It’s just the way that it goes. But I’m going to be able to look myself in the mirror at the end of my career and know that I did everything that I could and took every positive step forward in order to put myself in the best position to be there.”

Follow us on Twitter.