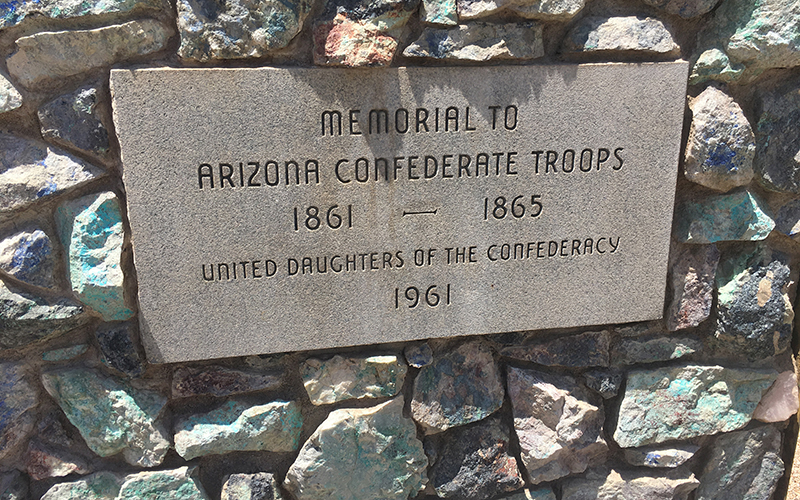

This memorial at Wesley Bolin Memorial Plaza near the Capitol is one of at least five monuments or locations honoring the Confederacy in Arizona. (Photo by Tyler Fingert/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Just before avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof fatally shot eight black worshippers and their pastor in 2015 at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, he was photographed posing with a Confederate flag.

About a month after the mass shooting, the Confederate flag was removed from the South Carolina Capitol, sparking a statewide and national debate to remove symbols of the Confederacy from public spaces.

Three years later, the momentum has continued.

Local and state governments have removed at least 110 Confederate tributes and monuments since the Charleston attack, according to an analysis published by the Southern Poverty Law Center this month. Arizona is not among them.

More than 1,700 symbols remain across the U.S., with many protected by state laws in former Confederate states, the report found.

Media reports frequently cite six Confederate memorials or monuments in Arizona, including one at the Capitol. However, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s database only lists five (one street name and four monuments).

The center did not include a Confederate memorial at a private cemetery in Phoenix or a memorial at a veterans’ cemetery in Cochise County, but it did include Robert E. Lee Street in Phoenix.

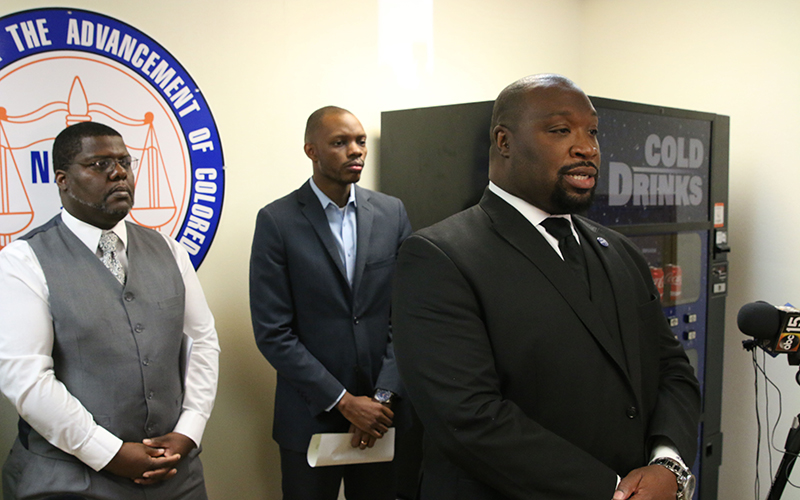

In 2017, civil-rights and faith leaders asked Arizona elected officials to remove the memorials, calling them symbols of terrorism and bigotry, according to a Cronkite News article.

Gov. Doug Ducey declined, saying “it’s important that people know our history,” according to the Arizona Capitol Times.

Vandals spray-painted and tarred and feathered a few of the Arizona memorials after President Donald Trump tweeted about the removal of Confederate statues and monuments, calling the action foolish.

Lecia Brooks, director of outreach at the Southern Poverty Law Center, said the Charleston shooting made the public pay attention.

“The conscience of the nation was pricked by that event,” she said. “It is time for us to have an honest conversation about what these monuments and memorials represent – it is not about heritage, it is about hate.”

The center’s report identified 772 monuments in 23 states and Washington, D.C., with more than 300 in Georgia, Virginia and North Carolina. There are 100 public schools named for Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis or other Confederate figures, and 80 counties and cities named after Confederate leaders, the report said.

Brooks said the law center did a national sweep to determine the scope of the remaining Confederate monuments, collecting data through online resources and contacts across the country.

Monuments and symbols should not be in public spaces because of what they represent,” she said, “and their removals are “past due.”

“The memorials and monuments themselves and honoring of the veterans of the Confederate war were born out of white supremacy, so it is a way to reinforce it and remind people, especially people of color and African-Americans in particular, that white supremacy reined,” Brooks said.

Activists pushing to remove these symbols and statues agree with the Southern Poverty Law Center, while opponents argue that removing them erases history. Experts and historians who spoke to News21 had divided opinions on the topic.

Ilya Somin, a professor of law at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, said there might be some areas where you can display them for historical purposes, but Confederate symbols should be removed from places of honor and public spaces.

The law center excluded thousands of memorials in historical settings, such as museums, battlefields and cemeteries, from its report.

“As a general rule,” Somin said, “I think the government should not be honoring people whose main claim to fame is that they were in defense of slavery.”

The removals since the Charleston massacre include 47 monuments and four flags, as well as name changes for 37 schools, seven roads, three buildings and seven parks, according to the law center’s report. Eighty-two removals were in former Confederate states, with Texas leading the way with 31 removed, followed by 14 in Virginia.

But the removals have brought controversy.

Last year in Charlottesville, Virginia, plans to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee, the Confederacy’s top general, triggered the Unite the Right rally in which white nationalists descended on the college town with torches to protest the statue’s removal; a counterprotest left one person dead and 28 injured. Federal hate crime charges were filed Wednesday against an Ohio man accused of plowing his car into the counterprotesters.

Some have argued that violent protests will continue as these monuments are removed. But Somin said that shouldn’t have any impact on the decision to remove them.

“If we do allow violent people to have a veto,” he said, “that just encourages more violence – not only by neo-Confederates, but by extremist groups of all kinds, both right and left, who if they see that you can get your way by threatening violence then that just encourages more people to do it.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center report also names monument sponsors, including the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which has erected hundreds of statues since the Civil War. A 2016 report by the law center said construction of monuments increased from 1900 through the 1920s, during the period of Jim Crow laws, and again in the 1950s-60s, during the civil-rights movement.

United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of the Confederate Veterans did not respond to requests to comment for this story.

Michele Bogart, a social history professor of public art, urban design and commercial culture at Stony Brook University in New York, said these monuments should not be removed because there is no inherent reason why people should assume that a historical artifact is “a validation or celebration” of the Confederacy today.

“If you get rid of the monuments, you’re not going to solve the problem of structural racism in American society,” Bogart said. “You lose a sense of place and individual character, and you lose a lot of local memory that is embodied in these works.”

This story was produced by the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Hate in America” national reporting project. Follow the project’s blog here. The full report will be released in August.

Follow us on Twitter.