TEMPE – A bearded man sporting a flannel shirt and worn Converse sneakers passes out syringes and vials of colorless liquid to a group of eager students.

Nathan Leach of the Sonoran Prevention Works, a nonprofit for people affected by drug use, is arming the public with naloxone, a life-saving antidote to an opioid overdose. It’s one step to addressing the opioid epidemic, which has killed more than 800 Arizonans in eight months.

Leach was training these Arizona State University students and others at the event on a new generation of first aid, just as people are trained on CPR for respiratory distress and the Heimlich maneuver to prevent choking deaths.

Naloxone is used by dozens of law enforcement agencies and fire departments statewide, and education on the use of the drug also is gaining traction with the general public. Leach conducts similar sessions in other parts of metro Phoenix.

Under Arizona’s recently enacted Good Samaritan law, people who help someone overdosing on a drug will not be prosecuted for drug-related crimes, although they could be prosecuted for other crimes.

Advocates say naloxone training will save lives but, as with any first-aid technique, those being trained need to be aware of risks and get overdose victims quickly to medical help.

The session on the Arizona State University Tempe campus was organized by Cody Holt, leader of Students for Sensible Drug Policy at Arizona State University. He doubts law enforcement officers would arrest someone for distributing or using naloxone kits, even though they technically are drug paraphernalia.

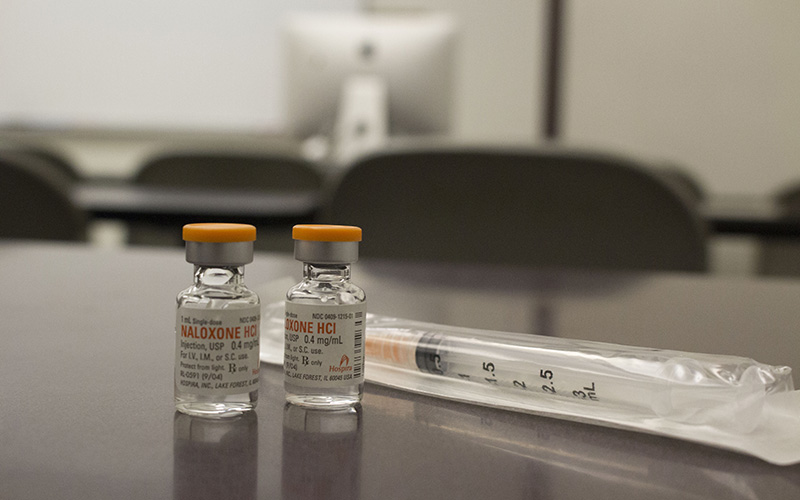

Cody Holt, leader of ASU’s Students for Sensible Drug Policy chapter, organized a training session for administering nalaoxone. Participants received a kit with syringes and two vials of the overdose reversal drug. (Amanda Slee/Cronkite News)

“There’s a precedent established already that this is in good faith, supplying communities and preventing overdoses,” Holt said.

Also, the Arizona Department of Health Services provides instructions for using the reversal drug via injection or a nasal spray.

Gov. Doug Ducey declared a public health emergency in Arizona last June, calling for a statewide push to reduce opioid deaths. In January, he signed the Arizona Opioid Epidemic Act, which outlines state initiatives to combat the crisis, including the Good Samaritan law.

Public safety officers and others administered 3,429 naloxone doses outside of the hospital from June to January, according to DHS. Eighty-six percent of overdose patients who survived received naloxone before going to the hospital.

The Phoenix Fire Department has been using naloxone on overdose calls for 30 years, said Capt. Rob McCade, a department spokesman. He said as opioid overdoses and deaths surge, naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, has become an even more essential tool for first responders.

“We’ve been using Narcan in a definitely more steady rate in the last few years,” McCade said. “That has to do with just the absolute prevalence of opiates, opiate-derivative drugs that are being taken recreationally by all ages.”

Students for Sensible Drug Policy is a nationwide organization “dedicated to ending the war on drugs,” according to the website. Although the college-student network “neither condones nor condemns” drug use, it aims to reduce stigma surrounding drug use and provide viable policy reforms.

Blanca Carrillo, who joined the ASU chapter in 2016, said she came to the naloxone training to become comfortable using the reversal drug. She was happy with the turnout, which included students and non-students.

“I definitely feel more confident and definitely more supported, because I know there’s this network of people that are also trying to actively reduce harm that affects people that are using drugs,” Carrillo said.

Leach, after discussing drug stigma and the opioid crisis, and giving step-by-step instruction for administering the reversal drug, Leach handed out free kits containing a syringe and two vials of the drug.

Leach highlighted the importance of trainings in a higher-education setting such as ASU, where young people who might be at-risk could benefit.

“Folks here may interact with drugs for the first time, and having informed choices to make that are evidence-based is really important to reduce the risks involved with doing drugs,” Leach said.

McCade, with Phoenix Fire, supports the idea of awareness and education.

“If it could save one life, then it’s definitely worth it,” he said, adding that people still need to be careful before deciding to administering naloxone.

“Any time that we would see the spread of a lifesaving drug or maneuver or any sort of lifesaving technique that can help the public, obviously we’re all for that,” McCade said. “However, I say that in a cautious way, because you are delivering a pharmaceutical that takes training to deliver.”

Although laypeople can learn to administer naloxone, he said, trouble could arise if the overdose victim also is on another drug, such as cocaine or methamphetamine. The victim might need an IV or cardiac drugs, for example, and someone not trained as a paramedic would be hard-pressed to help.

“It takes over a year of classroom work, hospital work, internships to become a paramedic, and that’s for a reason – to understand how to care for someone in this evolving medical situation,” McCade said.

Leach agreed it was important to get an overdose victim to paramedics or other medical personnel as soon as possible.