Workers in this 2010 file photo work on a multimillion-dollar project to rehabilitate the South Kaibab Trail at Grand Canyon National Park. The park has almost $330 million in deferred maintenance, the government says. (Photo by Michael Quinn,NPS/Creative Commons)

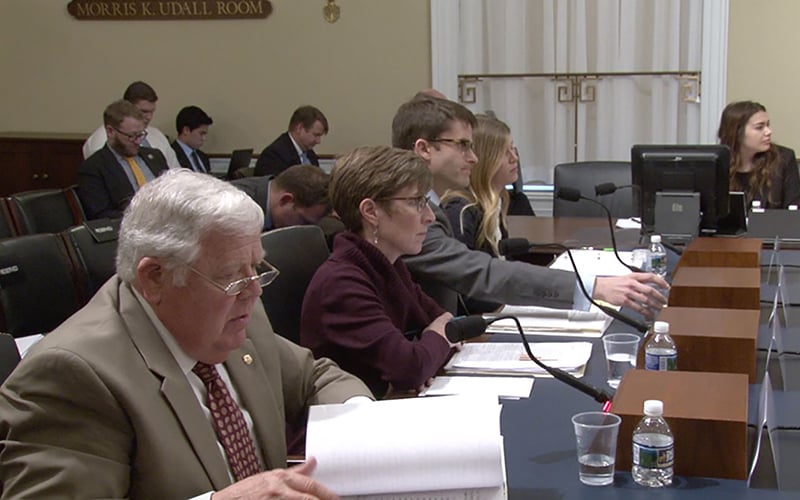

National Park Service Deputy Director P. Daniel Smith, left, and Matt Lee-Ashley, center, of the Center for American Progress told a House subcommittee that park maintenance needs funding, but they differed on how to get the money. (Photo by Ariana Bustos/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Witnesses and panelists on a House subcommittee agreed Tuesday that something needs to be done to close an $11.6 billion maintenance backlog in the national parks, but differed on how to pay for it.

The latest report from the National Park Service says more than $530 million of the deferred maintenance is in Arizona, with most of that – about $330 million – in the Grand Canyon. But lawmakers split over proposals to pay for work, including one that would dedicate revenues from energy development on federal lands.

“Should we be selling out the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to fix some bathrooms in the national parks? No, of course not,” said Matt Lee-Ashley, senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

“And the same goes with building a coal mine outside of a national monument, that’s not the appropriate activity for our public lands, especially not to be paying for potholes in parking lots on national parks,” Lee-Ashley said after the hearing before of the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Federal Lands.

He testified in support of the National Park Service Legacy Act of 2017, which would create a dedicated maintenance fund for the next 30 years, beginning with $50 million this year and gradually increasing to $500 million a year from fiscal 2027 through 2047.

But the National Park Service said it supports another bill, the National Park Restoration Act. That proposal would dedicate a portion of new energy revenues over the next 10 years, up to $18 billion, but could send significantly more per year to the parks during that decade than the other bill.

-Cronkite News video by Ariana Bustos

National Park Service Deputy Director P. Daniel Smith testified the service supports the second bill because parks could receive revenue from “all energy development” – mostly conventional sources like oil, gas and coal, but also from renewable energy sources.

“Without a dedicated funding source, the deferred maintenance backlog will continue to grow,” Smith said in his testimony. “The backlog of projects at our national parks limit access, impair visitor experiences and impact recreational opportunities.”

Deferred maintenance is not a new problem for the National Park Service. At the Grand Canyon, for example, the pipeline at the South Rim has “exceeded its expected life and now experiences frequent failures requiring continual maintenance in a remote and rugged environment,” according to the park service.

The backlog hit $11.9 billion as recently as 2015, with $580 million in Arizona, according to an annual report by the agency. It fell to $11.3 billion in 2016 and $565 million in the state in 2016. The national backlog bounced back up since then, but Arizona’s numbers continued to fall.

Lee-Ashley said while it is “absolutely vital” to invest in fixing problems like the Grand Canyon pipeline, funding should be provided for other federal land management agencies.

He said “it’s also important to understand how we pay for maintenance in the national parks,” adding that the bill supported by the park service is not the way to go.

“It’s extremely speculative,” Lee-Ashley said of the funding in the measure. “No money would go into this fund unless the United States dramatically expands drilling and mining in some of the most sensitive places we have.”

John Garder, senior director of budget and appropriations at the National Parks Conservation Association, said he is encouraged by the conversation and the fact that lawmakers are acknowledging the need to address the backlog. But he agreed the source of revenue can be a point of contention.

“The challenge with the restoration act is that we and others are concerned that the revenue source is uncertain,” Garder said. “The restoration act as it’s written does not depend on damaging energy extraction, but it’s a concern to us.”

Garder said the maintenance backlog is an issue that must be dealt with.

“These are our national treasures,” he said. “The backlog doesn’t only threaten the visitor experience, but the heritage of these historic sites.”