Bureau of Indian Education Director Tony Dearman said his agency is making progress on long-standing management problems and looks forward to next budget, claims challenged by members of a House panel. (Photo by Kyley Schultz/Cronkite News)

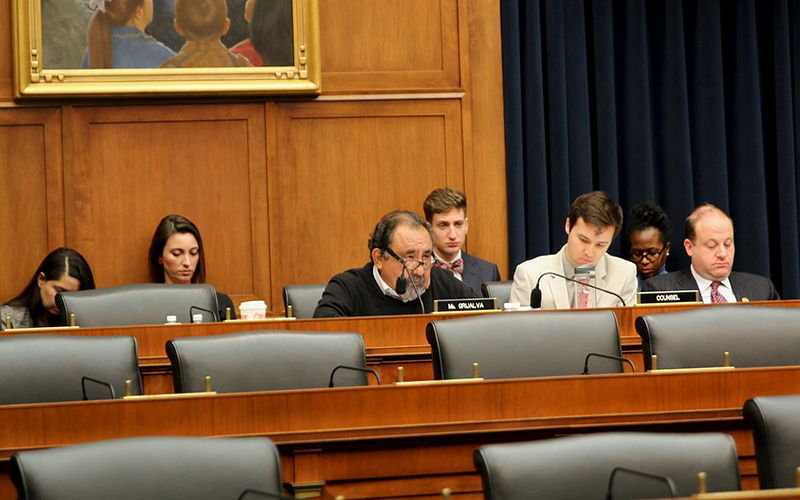

Many members of a House Education and the Workforce subcommittee, including Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, reacted skeptically to claims by the Bureau of Indian Education that proposed budget cuts would benefit tribal schools. (Photo by Kyley Schultz/Cronkite News)

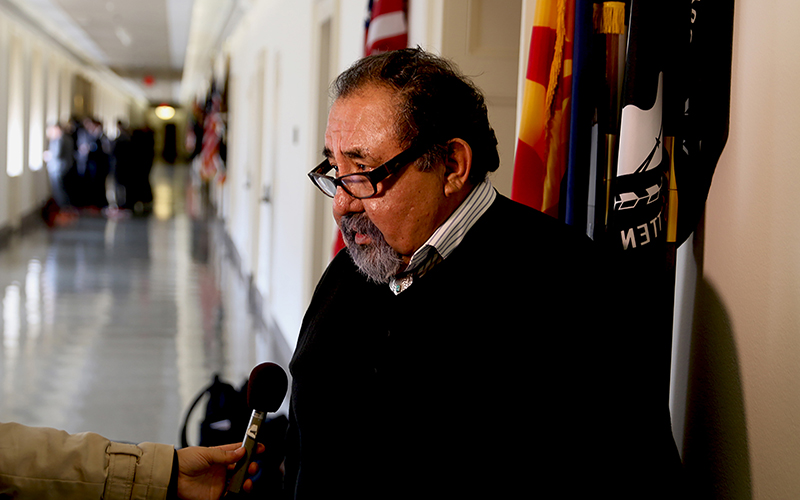

Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, said it “makes no sense” for the director of the Bureau of Indian Education to testify that a 16 percent cut to his agency’s funding under the adminstrations proposed budget would help tribal schoolkids. (Photo by Kyley Schultz/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – A Bureau of Indian Education official told lawmakers Wednesday that his agency is making “strong improvements” in the oversight of tribal schools, despite a long history of problems and proposed cuts to the bureau’s budget.

But BIE Director Tony Dearman’s testimony to a House Education and the Workforce subcommittee was criticized as “pretty naive” by Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Tucson, who said the system’s $1.3 billion backlog of repairs, poorly allocated resources and other problems will not be helped by cuts to school and social programs.

“For him to say that, ‘I’m excited about the fact that Trump cut our budget by 16 percent,’ to me makes no sense,” Grijalva said after Wednesday’s hearing. “Native kids who are as smart as anyone else are not performing well, and a lot of it has to do with the condition of schools and the attention that you give

to education.”

Other committee members also had sharp questions about the BIE, which was put on the Government Accountability Office’s “high risk” list of poorly managed agencies last year.

Members like Rep. Jared Polis, D-Colorado, recited a litany of problems with tribal schools: Polis said Native students’ four-year high school graduation of 53 percent remains among the lowest in the nation, that tribal students are too often identified as special-needs students and that schools suffer from low teacher retention and high expulsion rates.

Dearman said his agency, which oversees 47,000 students in 183 schools, has been working on a restructuring plan that includes increasing consultation with tribal councils, improving teacher retention rate and hiring personnel to improve data collection.

“We have been doing a lot of work, and our main goal is to get off of (the GAO’S) high risk by the next Congress,” Dearman said. “We’re working extremely hard on these improvements and are looking forward to working with the current administration.”

While she applauded those efforts, Rep. Virginia Foxx, R-North Carolina, also said “too many of us have the experience that agency reforms are just about shuffling chairs around and result in expanding an already confusing and fragmented bureaucracy.”

Dearman said much of the problem lies with inadequate school supplies, failing technology and transportation problems. He said those problems can be “significantly improved” with the passage of President Donald Trump’s budget, which includes an infrastructure plan that Dearman believes will help pay for BIE school repair and has the “potential to generate much-needed infrastructure and maintenance money.”

-Cronkite News video by Ariana Bustos

“If you visit any of our schools, we really need the infrastructure funds to support our facilities,” Dearman testified. “So we’re really excited about working with the budget because of that infrastructure focus.”

Democrats questioned Dearman’s embrace of the budget proposal.

“You’re excited about the budget, but my understanding is that the budget cuts BIE funding $143 million and 16 percent. Wouldn’t you be more excited about an increase than a decrease?” asked Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Virginia.

Rep. Todd Rokita, R-Indiana, said he appreciated the fact that Dearman, unlike many bureaucrats, did not resort to an appeal for more funding as the solution to his problems.

But Grijalva said that even if the infrastructure plan works – which he doubts – that it won’t solve problems in the schools, which he said need the social programs that the budget threatens to eliminate. He said those could include Indian community block grants and the Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee, as well as a 27 percent reduction in Indian Child Welfare Act funding.

“Those support services are vital and are connected to how a child performs,” said Grijalva, pointing to research that students do best when they have minimal stress and a sense of security at home. “The budget we saw from Trump and the cuts we are anticipating” do not do that, he said.

He said the White House’s infrastructure plan, which relies on local governments coming up with as much as 80 percent of a capital project, could hit smaller communities, like Gila Bend and San Luis, particularly hard.

“Their whole idea that local entities, and that includes tribes, would have to come up with 80 percent of the cost so that government can contribute 20 – that’s not going to happen,” Grijalva said. “They don’t have the resolve financially to do that now – what makes us think that because of this legislation we will be able to?”

“The infrastructure bill by Trump is built on a fantasy- we’re trying to interject some reality into it,” he said.