A Syrian woman, who asked not to be identified, prepares pastries. (Photo by Arren Kimbel-Sannit/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – President Donald Trump campaigned on a promise of putting America first by scaling back its foreign involvements and pledging to stem the tide of refugees from Syria and elsewhere to address terrorism.

He operationalized these promises not long after he took his oath in January, with a moratorium on almost all refugee resettlement and travel from several Muslim-majority countries, an order that’s now in its third iteration.

As it stands, the so-called travel ban now includes eight nations, six of which are majority Muslim: Chad, Syria, Iran, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, North Korea and Venezuela.

Trump also lowered the refugee admissions ceiling to 50,000. After July 13, when that limit was reached, only those with “a credible claim to a bona fide relationship” with someone in the U.S. would be eligible for refugee admissions, the U.S. State Department said at the time, though it reversed the limit in May.

Trump’s ceiling is half of what President Barack Obama set in his last year in office. Obama, whose policy measures are frequent targets of the Trump White House, expanded refugee admissions from 60,000 in 2008 to almost 75,000 in 2009.

Fewer came in the middle of his term. But as the Arab Spring fomented dissent and instability in the Middle East, refugees flooded in: almost 85,000 in 2016, the greatest number since 1999.

Now, the future of the ban is in the hands of the legal system. On Dec. 1, the U.S. Supreme Court temporarily reversed injunctions on the travel ban while the Trump administration files appeals. On Dec. 22, a panel of U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals judges unanimously ruled against the ban, though that decision has no impact because of the earlier Supreme Court ruling.

The 2018 budget for the Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, which dispenses grants to state refugee agencies and nonprofits across the country, requests $665 million less than the year before.

Arizona settles more refugees than most states, much of those efforts managed by the Department of Economic Security.

Repeated requests for an interview with officials from the Arizona Department of Economic Security and the state refugee coordinator were declined. The department provided only a written statement:

“Changing policy and fluctuating arrival levels most directly impact resettlement agencies that directly receive per capita funding for particular programs from both the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) and ORR in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to be distributed amongst their local affiliates,” said the statement from Arizona’s Refugee Resettlement Program.

Programs using grants to promote self-sufficiency in refugees were affected by the reduced ceiling, the DES statement said.

“We’ve been cautious with some of our spending, and we’ve been looking for additional private sources of funding,” said Stanford Prescott, community engagement coordinator with the International Rescue Committee, a prominent refugee advocacy and aid organization. “We continue to advocate for the needs of refugees at the federal level and the budget should reflect that.”

Editor’s note:

A previous version of this story misstated the per capita rate of refugee resettlement in Arizona in the 15th graf. The 4,100 refugees who settled in the state in 2016 translated to 60 refugees per 100,000 Arizona residents. The story here has been corrected, but clients who used earlier versions are asked to run the correction that can be found here.

In fiscal 2016, the state settled 4,110 refugees — sixth-most in the U.S. and, at 60 refugees per 100,000 Arizona residents, one of the highest rates of resettlement per capita in the nation, according to a report by the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center. Most came from Iraq, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, all countries that have faced terrorism, civil conflict and a collapse of government services in recent years.

The federal government foots the bill for the state, although national budget cuts may impact Arizona. The state’s admissions numbers already have dwindled following the refugee ban. It settled 87 refugees in April 2017, down from 547 the previous October, according to the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center.

But while a continuing resolution keeps federal agencies operational until the end of the fiscal year, the process is ongoing. Cuts to government-funded refugee programs represent the national uncertainty on the issue.

Although refugee policy generally is handled on the federal level, Arizona legislators have made repeated efforts to hinder or stop admissions and resettlement in the state, most recently with a failed bill in February.

State Sen. Judy Burges, a Republican from Sun City West, proposed a bill that would circumvent federal refugee authority by levying a $1,000 a day fine on charities that aid refugees. It also set out to suspend DES’ participation in refugee resettlement, though that wouldn’t stop refugees from coming.

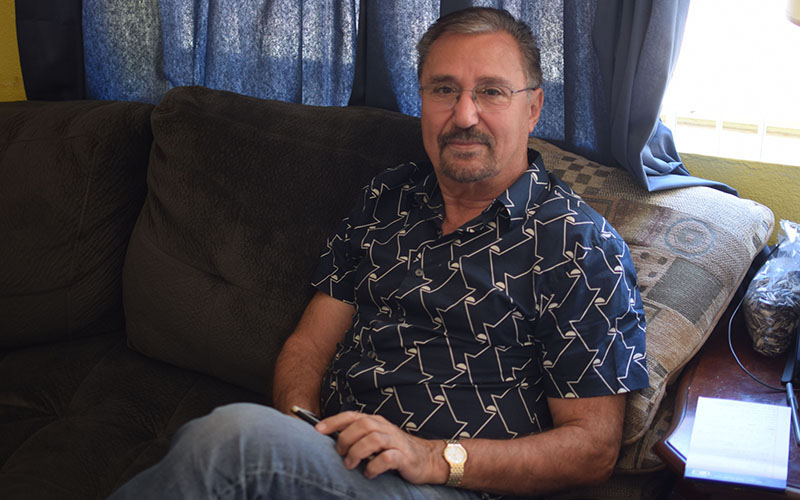

Steve Arkawi, a Syrian man who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1960s and leads the Phoenix chapter of the Syrian American Council, advocated at the legislature on behalf of the refugee families he supports.

He said Arizonans should appeal to their sense of humanity to help refugees and called for further cash assistance, and a forgiveness of travel debt.

“These people, they need help,” he said. “And in this nation, we’re all refugees.”

“Arizona is not helping as it should,” he added, calling politicians such as Burges “overzealous.”

Subaia Alaktaa is a 37-year-old Syrian refugee from Homs, which served as a rebel stronghold in the Syrian Civil War until falling to government forces in 2015.

Alaktaa, who lives in Phoenix, has five young children, and his wife is 8-months pregnant. He can’t work because of back and neck injuries and nerve damage from a 22-day stint in a Syrian jail.

“They hit me so hard, they almost crucified me to the wall,” he said in Arabic, through Arkawi, who served as a translator.

He said he was arrested with several friends for no apparent reason, and that he was the only survivor.

Steve Arkawi sits in the home of one of the refugee families he assists. (Photo by Arren Kimbel-Sannit/Cronkite News)

Now, aside from $500 a month from the government to help with the children, his family has no steady income, he said. He has to pay $6,500 for his journey from a refugee camp in Jordan to the U.S., and pay back a loan he used for rent.

Alaktaa said he wants to get government-subsidized housing, but without a green card, he can’t. Though he is aware of the travel ban and other refugee-targeted policies, he says, “I don’t have an opinion, I’m not so much involved in politics.”

“I just want to make a living.”

Prescott said the bill was bad policy because the state cannot stop refugees from coming entirely.

If a state decides to cease its refugee resettlement operations, the federal government will set up a non-profit in its place, Prescott said. In that scenario, the state would arguably have less control over refugee resettlement than it did to begin with, he said.

He said refugees aren’t terrorists — rather, they’re the ones fleeing terror. And moreover, “they hold close to $1 billion in purchasing power in Arizona,” he said.

Ron Johnson, the executive director for the Arizona Catholic Conference, lobbied against the bill on behalf of Catholic Charities.

“Effectively, it would have created punishments or fines to people who help refugees,” he said.

But he said that bills like Burges’ are addressing the wrong part of the refugee issue.

“Our job is, once they get here, we’re the good Samaritans that help them,” he said. “We want them to be productive people in our country. I think the target was on the wrong people, if you want to use those words.”

He said he supports the vetting of refugees — an already lengthy process — but that’s the purview of the federal authorities.

The impetus for the shift in Arizona politics, came with the November 2015 Islamic State terrorist attacks in Paris, he said. Several governors took a hard line against refugees following the attacks, including Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, who called for an immediate halt in the placement of any new refugees in Arizona.

“I don’t know how widespread the feeling is, but what’s happened is the refugees, instead of a group that has been victimized and want to be welcomed, we’re seeing them through the lens of national security and the microscopic chance that there’s terror,” said David Wells, a political scientist at Arizona State University.

Steve Farley, an Arizona Democratic state senator who has been a strong advocate for refugees at the legislature, heads a web-based advocacy group called Arizona Welcomes Refugees, which holds fundraisers to help refugees pay back travel costs.

The group also serves as a de facto welcoming committee for refugees when they first land in the state.

“What we came up with is, well, do you think we could just welcome them at the airport?” Farley said. “To reassure them that this is their new country.”

But when Trump took office, the group stopped going to the airport for fear of unwanted publicity, he said.

“Refugees were being re-traumatized by the kind of rhetoric we’re hearing,” he said. “There are certain demagogues who are trying to, for partisan purposes, manipulate people to benefit their future instead of working to make the state safe.”

Within a few days of the Paris attacks, the U.S. House of Representatives easily passed a bill seeking to limit Syrian and Iraqi refugees into the countries, though it did not become law. In December, just after the mass shooting in San Bernadino, then-candidate Donald Trump announced his plans for a so-called Muslim ban.

Wells said that the travel ban does not address concerns of terrorism realistically. For example, the ban did not target Saudi Arabia — the home of most of the 9/11 hijackers and a major U.S. ally in the Middle East.

“They’re not politically convenient,” he said.

And with every hitch in the resettlement process, and with every new variation of the travel ban, uncertainty grew for refugees.

“What we saw was that when (the ban) was in place for a few months, then it would go away and be in place again, their clearances would expire and they’d have to reapply for another clearance,” Prescott said.

For the refugees and refugee agencies caught in the judicial crossfire, the next step is further outreach and advocacy.

“What I would say is, I think in the larger community, I think there’s a lot of support for refugees, but just as it is in the legislature, there’s people who could know more,” Prescott said. “It’s our work to make sure the public knows.”